The American essayist Fredric Jameson died recently. One of his most famous quips (sometimes wrongly attributed to me) holds today more than ever: it is easier for us to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. What if we apply the same logic to Jameson himself? His entire way of life was much closer to what the French call les palissades, the stating of the obvious attributed to the mythical figure of Monsieur la Palice, like: “One hour before his death, Monsieur la Palice was still fully alive.” For Jameson, death didn’t exist as long as he was still alive. I learned from Jameson’s family that he continued reading and writing until his last moments: a day or two before his death, he asked them to bring him a couple of books and a notebook to his hospital bed. So it was not Jameson who died, death just happened to him.

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis has deservedly flopped. This obscenely expensive project provides the best argument for studios having tight control over productions: if a director is given too much freedom, this is the result. The only thing I liked about the film, a retelling of Catiline’s rebellion crushed by Cicero set in a near-future New York, is that it sides with Catiline. I think she was an advocate for the poor and dispossessed, fighting for a more fair distribution of wealth and land. However, for this reason I find the film’s ending repellent: we get the worst imaginable version, a big reconciliation between Catiline and Cicero (a corrupted mayor). Instead of being a social revolutionary, Catiline is an architect with a big project of how to rebuild New York. If I were to hold political power, I would turn into Joseph Goebbels in this case: Megalopolis would be publicly burned.

At the beginning of World War One, when Germany invaded Belgium, one Belgian minister said: “Whatever historians will say later about this war, nobody will be able to say that Belgium attacked Germany.” Respect for obvious facts no longer holds today: Russia has claimed that Ukraine was the antagonist ever since the 2022 full-scale invasion. Some weeks ago, Vladimir Putin’s government released a list of forty-eight foreign states and territories accused of implementing policies that impose destructive neoliberal ideology, and which contradict traditional Russian spiritual and moral values. Countries on this list are officially designated as “enemy states” — there is no talk here about a multipolar world; you’re the enemy of Russia if you don’t hold the same values. These values, though, are somehow shared by North Korea and Afghanistan. But Russia isn’t cheating: they are bonded together in their rejection of the European Enlightenment, viewing it as history’s ultimate evil.

Lately, I have been exchanging messages again with Nadya Tolokonnikova, a founding member of the group Pussy Riot. Back in 2012, these Russian dissidents caused a scandal by staging a protest in a St. Petersburg church. Their performance was against Russian orthodoxy being exploited by Putin’s regime. They were right: recall that Patriarch Kirill, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, called Putin “a fighter against the Antichrist” and “chief exorcist.” Despite never meeting, we corresponded throughout her imprisonment. Her letters, written in secret, were smuggled out of the prison by her lawyers and published in Comradely Greetings. She criticizes the regime from a radical leftist standpoint, and I admire her courage and ethical integrity. We are meeting for the first time in person next month at a round table in Vienna. I’m not afraid that the real person will disappoint me, as usually happens when I meet “famous” people.

Charles Dickens always made sure his bed was facing north

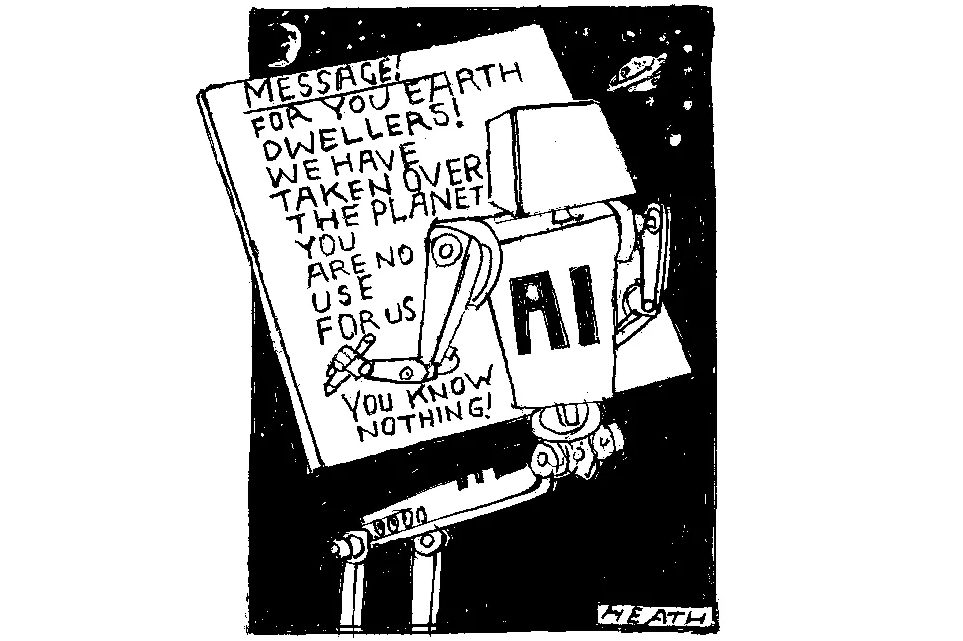

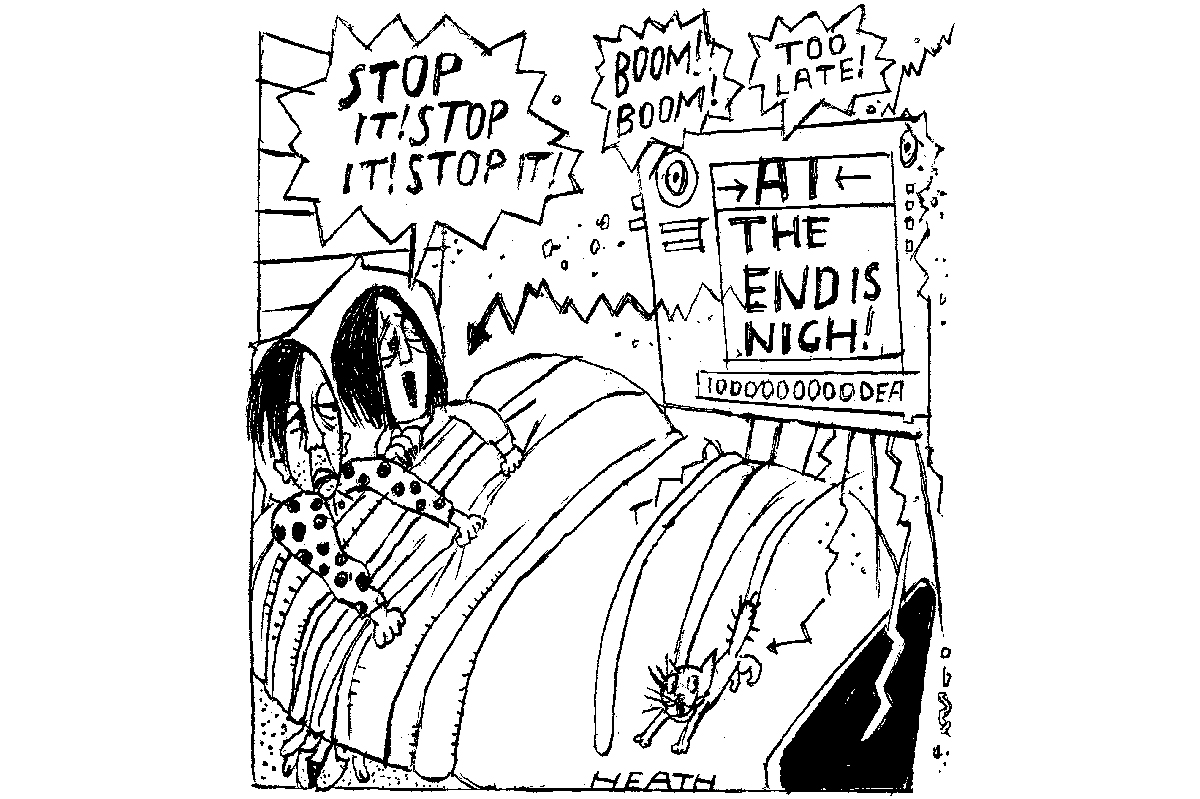

Microsoft recently claimed that AI assistants are coming soon. But there’s surely a limit to what they can do. How, for instance, can small daily rituals be programmed? Take a few well-known examples. When Maya Angelou arrives at a hotel room, she always asks for the pictures to be removed from the walls. After finishing her writing in the early evening, Agatha Christie took a bath and ate an apple there. Charles Dickens always made sure his bed was facing north. Serena Williams bounced the ball five times before her first serve… We all have our own habits that make life meaningful yet have no pragmatic function. Their meaning is purely self-referential, residing in the effect of meaning. It’ll be a long time before AI will be able to assist humans with finding order among the chaos.

Friends tell me that I am popular on TikTok. I don’t know why, because I have never been on it or any of the other digital platforms. The way they function is totally strange to me. I hate quick repartee and need time to reflect. But at various times I’ve been alerted by friends to the fact that there are a couple of accounts pretending to be me. The funny part is that although they try to imitate my thinking, they usually always attribute me with wrong political or philosophical positions. I don’t have the time to protest about these misappropriations, though a couple of times I’ve been tempted to reply under a pseudonym, attacking myself.

I recently participated in a debate in London about quantum mechanics, with Roger Penrose and Sabine Hossenfelder, and I must confess it was a very depressing event. The three of us simply talked past each other. There was not even a clear conflict — just total miscommunication. Sadly, the debate was a missed opportunity, I largely blame myself for this failure, because I too abruptly focused on basic philosophical questions, not for the first — nor probably the last — time.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply