In the week following the October 7 attacks by Hamas, a journalist in Beirut put the question all of Lebanon wanted to ask to the prime minister, Najib Mikati: do we have to be dragged into the war with Israel?

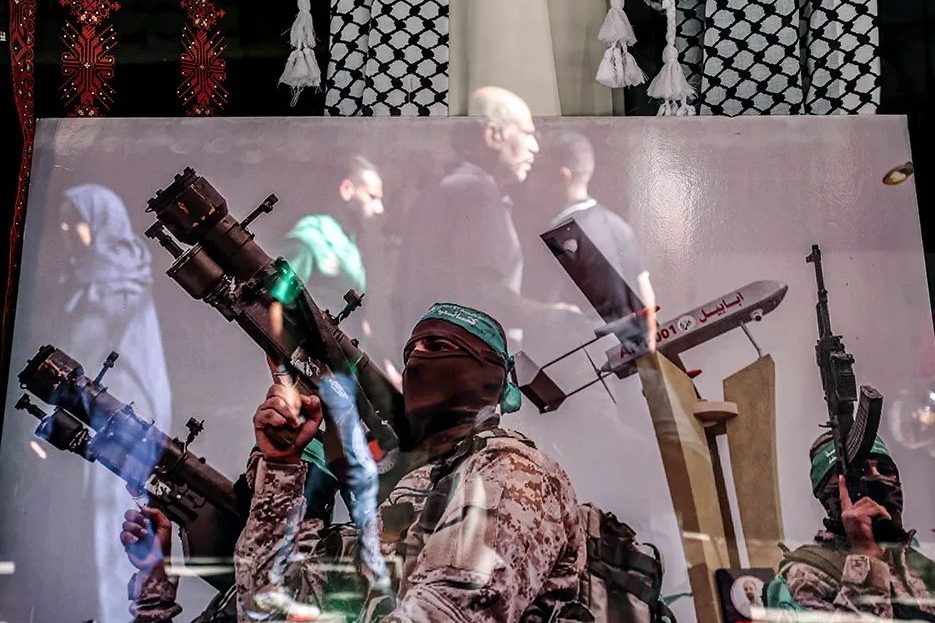

It was more of a cri de coeur than a question, because the whole country knows the answer and knows that Lebanon has no choice. Hezbollah, the Shia Islamist party and militant group, unofficially controls many, if not most, of the levers of power in Lebanon and it does not answer to the people or the government here. Hezbollah’s leader, the reclusive cleric Hassan Nasrallah, holds no public office and he doesn’t give a stuff about Mikati’s government. He takes orders only from Tehran. On November 3, in a televised speech to the party faithful, Nasrallah, who had till then been silent on the conflict, read Israel the riot act. His party, he said, was ready for any escalation, and would match any atrocity on Lebanese soil with a similar action across the border.

Lebanon acts as a regional weathervane, shifting and adapting to the winds of the Middle East

This was dismal news. The vast majority of Lebanon is sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, but we do not want another conflict. We hold on to the hope that despite stern assurances it is prepared to deal ruthlessly with its old enemy, Israel does not want to fight on two fronts and that Hezbollah, for its part, is reluctant to tarnish its hard-won martial glory. In 2006 it fought Israel to a standstill in a bloody month-long summer war and it knows that, despite Nasrallah’s saber-rattling, any “rematch” would not be as close. So, for the moment, both sides are abiding by the established conventions of cross-border niceties — a few Hezbollah rockets followed by token Israeli retaliation.

But Lebanon’s margin of error is shrinking by the day: casualties on both sides are mounting and Israeli artillery barrages are creeping north. They have reached the outskirts of Sidon, around twenty-four miles from Beirut, and the inland town of Jezzine. Any “mistake” by either side in which there are significant civilian deaths will spell disaster.

In the mainly Christian town of Marjaayoun, six miles north of Lebanon’s tense border region, I spoke to Carol Khoury, who owns the Vignes du Marje, one of two wineries in the area. Carol told me that those who can have moved to Beirut, though she is still holding on to the hope that things won’t escalate: “The whole of Lebanon will go up in smoke if they do.” But she has shipped all her wine to the capital, because “who knows?”

To the west, in the coastal town of Tyre, Zeinab Charafeddine, who comes from a historic and well-respected Shia family, also hopes there is a chance things won’t deteriorate. Hezbollah “won” in 2006. Why risk losing now, especially as popular support has declined, she told me. “Many Shia are disaffected because of the terrible economic situation Hezbollah has helped create.”

Any analysis of how Lebanon will react or how people here feel requires an understanding of the “confessional system,” with power distributed between eighteen official “confessions” or sects — Judaism still included, despite there being only a handful of Jews still in the country. It is because of this myriad of sects that Lebanon acts as a regional weathervane, shifting and adapting to the winds of the Middle East. Lebanon’s various sects each have a different history in their relations with Israel.

On June 6, 1982, Israel launched a three-pronged invasion of south Lebanon to remove the thousands of Palestinian guerillas who had established a presence in the area after being expelled from Jordan during the 1971 Black September War. In the same conflict, the Lebanese Christian Phalangist Party was Israel’s key ally in its bid to eradicate the Palestinian military presence. The Christian sects, Maronites in particular, felt their nation was under threat from an increasingly belligerent PLO, which had the backing of the Sunni Arab states. The Phalangists saw the Israelis as natural partners, closer in religion and culture than many of their compatriots. The alliance reached its bloody denouement on September 16. Christian militiamen — with the tacit “approval” of Israel — massacred more than 2,000 Palestinians, mainly the elderly and women and children, in refugee camps on the outskirts of Beirut.

Pro-Israeli attitudes still prevail in the Christian enclaves despite the shame of that day. The week after the October 7 attack, I was at lunch in a Maronite village where a man who was too young to have fought in the civil war openly said that he admired Israel; admired their lifestyle; admired what they had done for themselves. The Palestinians? Well they only had themselves to blame if they supported Hamas.

Not all Lebanese share this view. There are thousands who have lived through multiple conflicts with Israel and were happy at what Hamas did that Saturday morning. They are not monsters. They merely saw October 7 as a “you had it coming” moment. The Lebanese Sunnis in particular stand with the Palestinians. They, more than most, believe in the concept of nusrat el akhareen — “standing with my brother” — and it was they who, as part of the leftist Lebanese National Movement, fought alongside the PLO in the early years of the civil war.

A more balanced view can be found among the apolitical Lebanese, the educated professionals who hover above the hardcore sectarians. They deplore not only Israel’s decades-old treatment of the Palestinians and its regular rampaging through, and over, Lebanon, but also the death-cult ideology of Hamas and Hezbollah, in particular the latter’s hijacking of the Lebanese state.

The economic background in Lebanon is dire. The state has disintegrated and the economy is in shreds. Many Lebanese believe that another war would accelerate the often-discussed partitioning of the country into sectarian cantons. I raised this with my butcher in a Mount Lebanon village the day after the October 7 attacks. “Why not?” shrugged George, a Maronite from Bikfaya, the hometown of the slain president Bashir Gemayel. “We were never really a country to start with, were we? Let’s do it and let everyone get on with their own life.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply