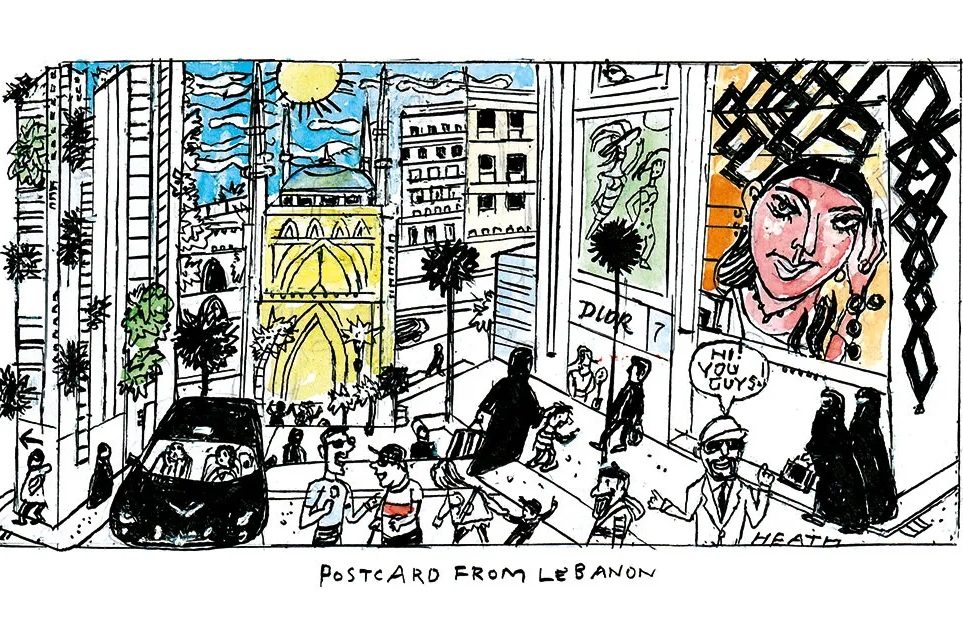

You might have thought that the threat of the Gaza war spiraling into an all-out regional conflagration, along with breathless travel advice from western governments urging their nationals to leave the country, would have deterred Lebanon’s expats from flying home to celebrate Eid al-Fitr this year. Not one bit. Flights, hotels and restaurants were fully booked despite Iran’s drone strike.

The Lebanese know that even if there is fighting (and in South Lebanon, there is on an almost daily basis), if it isn’t on your doorstep, there’s no reason to stop the party.

The Lebanese know that even if there is fighting, if it isn’t on your doorstep, there’s no reason to stop the party

In any case, the Lebanese always think they have the inside track. “We knew it wouldn’t come to much,” a friend assured me after Beirut airport reopened at 7 am on Sunday. “There was a deal. No one wanted an escalation. It was less dangerous than a night out in London.”

This cheery indifference to danger and an almost fanatical obsession with finding any excuse to come home is typically Lebanese and, ironically, a by-product of a long history of emigration, one that has existed since the first millennium before Christ when King Hiram of Tyre despatched his people across the sea to establish trading colonies. Since then, poverty, persecution, war — in some cases all three — have been contributing factors. We Lebanese go abroad; we work, we make money, we come back and show everyone how well we’ve done by building a McMansion.

Take my Lebanese grandfather. Sometime in the late nineteenth century he killed a man who insulted his mother. His father put him on a boat to Brazil where he opened a trading company, became a freemason, married a Swede and, when the heat had died down, returned to his village, a relatively prosperous man with a foreign wife.

It’s true that more people are leaving and the country is experiencing one of its periodic episodes of existential anxiety. The 2019 collapse of the banking sector and the subsequent hyperinflation mean there are no genuine job opportunities for a workforce stuffed to the gills with graduates.

The UAE has long since taken over from Brazil as the destination of choice, but Montreal, Melbourne, London and Paris also have thriving Lebanese communities. In West and Central Africa, they run the show, trading everything from ball bearings to blood diamonds. But wherever they live, the new priority is to wire money home to parents whose life savings and pensions were wiped out in the crash.

But ultimately, despite what the politicians and the religious leaders fear about losing their constituents and a shifting sectarian balance, the majority of the diaspora will always return. Yes there are more people of Lebanese descent outside the country than in it, but gone are the days when people left and never came back. My grandfather and his brother returned from Brazil but another stayed. That’s a 66 percent success rate at a time when journeys were major undertakings. My daughter, who runs an art gallery in Mayfair and can basically travel anywhere she wants, flew into Beirut for New Year’s Eve, when return tickets from London were changing hands for well over $1,200. Her school friends, who live and work in Bahrain and Los Angeles, were in town and she “needed” to go.

In the last week of Lent, I met a group of wine-making Maronite monks at the St. Moussa monastery in the Upper Matn district of Mount Lebanon who have made it their mission to thwart any exodus by convincing those in rural communities to stay and get involved in Lebanon’s burgeoning wine industry. “We have a close relationship with the vine,” said Father Youhanna, the head winemaker, who had just returned from studying the industry in Australia. “We want people to stay on their land.” By “on” I felt he really meant “in.”

That afternoon, I attended a church service for a cousin who had died in Canada after living there for more than thirty years. He had wanted his ashes brought back to his village where the urn was duly placed in the same vault as his grandfather and Swedish grandmother, as well as his aunts and uncles, including my father, who died in Africa.

As I was leaving, I bumped into the priest and, possibly a bit too cheerfully, asked him if he’d ever held a service for an urn of ashes. “More and more,” he replied. “They all want to come home. Sometimes they come by DHL.” We both laughed and then stood in silence. He pointed to the ground and tapped his foot for emphasis. “Hawn akhretna.” Here is our end.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply