Daniel Penny is heading back to a New York courthouse today to face charges for the murder of Jordan Neely. Penny, with the help two other bystanders, held Neely, who had a criminal history and mental health issues, in a chokehold after Neely made repeated threats to other passengers on a subway car. Neely died during the incident — and Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg chose to indict Penny for second-degree murder, despite downgrading over 50 percent of felonies to misdemeanors in 2022.

Crime has risen in New York City since 2020, and the city has done precious little to address it, though Mayor Eric Adams has been slightly more proactive than his predecessor, Bill de Blasio. Go back a few decades, however, and you find the Big Apple in an almost unimaginably worse situation. That period, and the extraordinarily successful efforts to bring peace and prosperity back to the city, is the subject of a new documentary film, Gotham: The Fall and Rise of New York. The film primarily covers developments under the mayoralty of Rudy Giuliani from 1994-2002, and the drastic improvements in crime, education and the fiscal status of the city. If New York City could lift itself out of the hole it was in during the early years of the 1990s, then it can pull itself out today. But doing so takes a concerted effort and good policy — both of which are currently lacking.

Under Commissioner William Bratton of the New York Police Department (who would go on to be the police commissioner of Los Angeles), monumental changes were made to how crime was fought. Bratton implemented the now-famous “broken windows” policing, whereby the NYPD would police quality of life issues and “small” crimes, with the intent of preventing worse crimes from happening. A simple but extremely effective application of this policy was in the subways, which then, as now, were one of the focal points of crime. “Too many people were jumping the turnstiles,” Larry Mone, executive producer of Gotham and former president of the Manhattan Institute, told The Spectator, “and [Bratton] made it a priority for the police to stop everyone going through the turnstiles, regardless of [who they were]… But what turned out was that a significant percentage of people that were going through the turnstiles had previous records.”

Stopping and punishing a petty crime like jumping the turnstiles ended up massively reducing overall crime on the subways. “You have to think of crime fighting as proactive,” Mone said. “You are not apprehending people who already [did] a bad thing, you are trying to create a situation where you prevent bad things from happening.” Had this been going on in the subways now, the altercation between Penny and Neely likely never would have happened.

If you live in the city, the lack of proactive policing is likely evident almost every day — just go into your local pharmacy. “The most extraordinary phenomenon that I have seen,” Mone said, “is when you walk into your local CVS… everything in the CVS store is locked up. So there is the choice we have made: you can either lock up people who steal from CVS or you lock up CVS.”

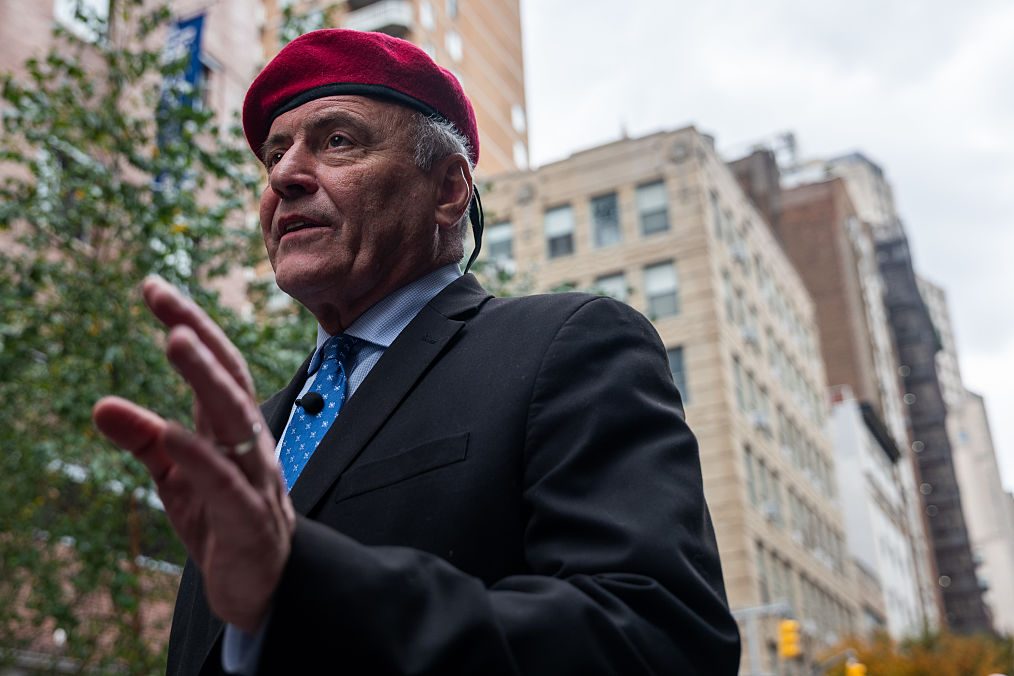

Responsibility for these failures lies squarely with the leadership of both New York City and New York State. “You had a lack of support across the board, from the Albany politicians, to the New York City council, to the mayor’s office,” said Louis Anemone, New York police chief from 1995-1999. “They are talking about defunding the police, they changed a lot of the laws in 2019 and 2018, they raised the age of culpability, they changed the bail procedures, they changed the discovery laws… what conclusion can you draw from actions like that?”

Decisions by progressive prosecutors, like Alvin Bragg’s refusal to go after lower-level crimes, demoralizes the police force and disincentives policing. “It doesn’t take long for a [police] department to say ‘Listen, why am I spending money and time grabbing people at the turnstiles when before the cop is finished with his paperwork the DA is saying he is not going to prosecute, send them home?’” said Anemone. “They [prosecutors] had a way of determining exactly what the cops were going to do just by negating any proactive work that the cops were doing, and the cops learned.”

Anemone said that some of this is changing under Mayor Adams, with an uptick in quality of life policing regarding illegal scooters, motorcycles and fake license plates. It is a good sign, but there is a long way to go.

The other critical issue — and this is one that has been around for decades — is the lack of mental health facilities. Jordan Neely desperately needed medical help, but New York, like most of the US, has very little institutional capacity and very little will to deal with the issue. “Going forward, I think we need to be much more aggressive about institutionalizing mentally ill people who can’t take care of themselves,” said Mone.

Part of the crisis is due to deinstitutionalization, which was sparked by revelations of horrible mistreatment in mental health institutions. “They [politicians] threw out the baby with the bathwater,” said Anemone. “The pendulum swung so far in the other direction, so there is absolutely no place for people [with serious mental illness].” Creating institutions where the humane treatment of patients is rigorously monitored and enforced will be key.

The other problem, however, is funding. “Medicaid does not pay for states to build psychiatric units — it pays to build nursing homes and other kinds of facilities, hence you see a lot of those facilities,” said Mone. “So all of the money has to come out of the state pocket… it is a money issue as much as a philosophical issue.” It will take both a change in philosophy and federal entitlement policy to address the crisis. Unfortunately, with the country’s current state of polarization, neither seems likely.

Ultimately, what happened with Daniel Penny and Jordan Neely is a consequence of the city failing to do its job. “I think there is going to be a public outrage if there is a really negative result for him [Penny],” Mone said, “because the public is thinking that if you are not going to protect us, how can you penalize ourselves for protecting ourselves?” Officials know what they have to do to get crime under control, as Gotham so deftly illustrates. The question is whether they are interested in doing it — and until they decide that they are, we can expect the tragedies to continue.