It was on Christmas morning in Moscow in 1990 that my daughter, then aged seven, realized that Santa Claus was not to be trusted. She had made the usual elaborate suggestions to him in a letter to Lapland (perhaps hoping that, being posted from a frozen region, it would get through more readily). But when she came to rip open her gifts, the parcels did not contain the things she had hoped for. Instead, they were full of pale, oddly colored and sometimes faintly dangerous Soviet products, breathing the last enchantments of the 1930s. Mrs Hitchens had lined up fiercely to buy these delights in the colossal “Children’s World” department store which stood just across the road from KGB headquarters. Christmas in the Evil Empire was different, you see, though not always worse.

By the time we went to live there, at the end of the Gorbachev era, the festival was no longer actually banned in Soviet Moscow. Young Pioneers no longer patrolled the wintry streets searching for subversive Christmas trees, as they had done in the early years of the Leninist state. The air no longer trembled with the sound of cathedrals being dynamited, or of great bells being torn from their towers and spitefully smashed, as it had done in Stalin’s day. There were even attempts to restore some of the many Orthodox churches and monasteries desecrated and befouled by use as warehouses or reformatories.

The League of the Militant Godless, once a huge semi-official organization dedicated to mockery and hatred of God, of priests and believers, had quietly vanished during the war against Hitler. God had, during that odd period, proved a useful Comrade, at least as long as the war went on. He had been exiled and canceled again since, but not with quite the same scorn as before.

In any case, our western nativity festival was far too early for those remaining Russians who had somehow managed to cling to faith during the long decades of murder, desecration, intimidation and outright persecution. Orthodox Christmas, still governed by a more ancient calendar than ours, falls in early January. And in 1990, an Anglican Christmas in the Soviet capital was still a personal matter. St. Andrew’s Anglican Church, in Victorian times the center of a thriving English community on the very borders of western civilization, was still at that time requisitioned by a cold-hearted atheist government, and forced to serve as a state-run recording studio. So it was just us and a tatty copy of the 1662 Prayer Book.

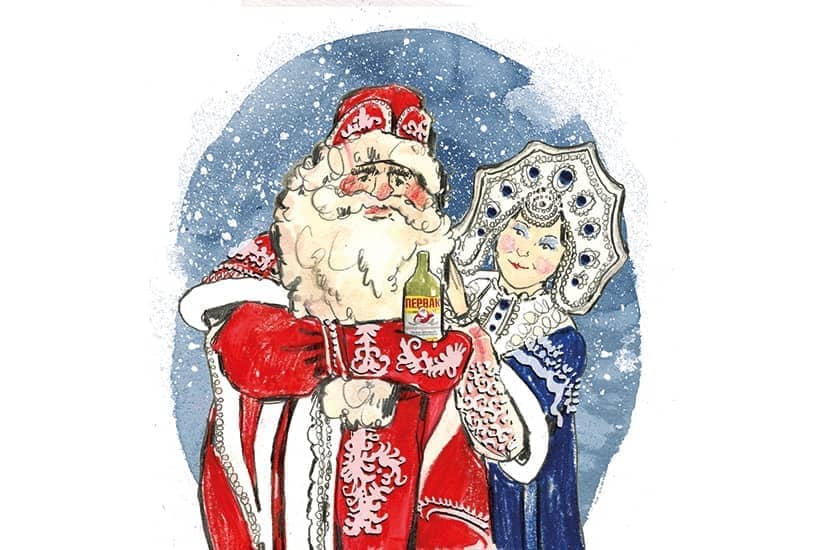

The Kremlin had sought, fairly successfully, to blot out all recollection of the birth of Our Savior from normal life, especially among children. Instead it had encouraged a huge celebration of the New Year, just a few days before the Orthodox Nativity. Stalin had even abandoned his original attempt to eradicate the Russian Santa Claus, a hard-drinking, white-bearded character called Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost) and his female subordinate, the Snow Maiden. People liked them too much, so the Communist Party had repurposed them to serve the new order. They were absorbed into the Atheist New Year festivities, including a communist New Year tree that looked suspiciously like a Christmas tree, unless adorned with an official red star.

The New Year feast was all-encompassing, impressive and impossible to ignore. The street on which we lived was an immensely wide avenue built for giants. It roared day and night with dirty, spluttering vehicles, its center lane much used by the Politburo’s huge, snarling limousines. Yet even this highway fell silent for the holiday. And in that dark city, it was astonishing to see the festive lights switched on, making it, for a few brief hours, as bright as a western capital. But this was not our celebration. It was its enemy. I have disliked the New Year heartily ever since.

So in 1990, our first Christmas in the Russian capital — and what would turn out to be the last Christmas in the USSR — our western Christian arrangements were pretty much up to us, in the few square yards we occupied. What were we to do to mark it out from the normal, crazy days of Soviet life? We did not, as some expatriates did, believe in hurrying back home as often as we could. We had decided to live in Moscow, and we were damned well going to do so, apart from an annual few weeks in the summer.

In those days it was dangerous to the spirit to go home, even for a day or two. You immediately lost the hard carapace of grim humor and shared adversity, built up over months of endurance, and you had to spend miserable weeks readjusting again on your return. Better, we thought, to stay and put up with it. You might, in that way, discover unexpected pleasures, and we did. We took family holidays in Samarkand or on the Black Sea, learned to bribe doormen and waiters at enjoyable Soviet restaurants, and went for weekends away in Leningrad or Kiev.

My wife, the daughter and granddaughter of troublemaking journalists, was not dismayed by the twisted, corrupt yet often thrilling confusion of dying communism. She had been with me several times into the communist world, which fascinated us. She had not been surprised, the previous Christmas Eve, to find herself taking down my report from Bucharest, dictated while I hid under the bed as tracer bullets went whizzing past my hotel. “Whatever is that noise?” she asked me at one point. She drove our mangled Volvo (rammed by a Soviet lorry and virtually impossible to repair) down the immense streets with their mad traffic and their vast craters filled with freezing chocolate-colored mud and did not mind. So contriving a family Christmas in the capital of the Evil Empire was just another task. And so to her we owed two very lovely Christmases, quite unlike anything before or since.

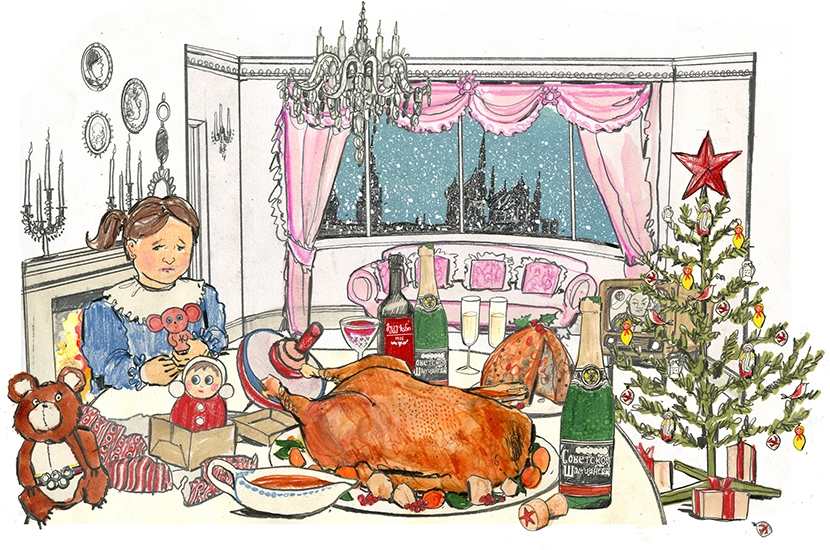

The first, and most moving, was in our beautiful and illegally rented elite apartment, with its haunting views across the mysterious city, where our neighbors were mostly KGB high-ups or worse. The Brezhnev family lived in a vast flat on the opposite side of the snowy courtyard, patrolled by a severe neighborhood watch of beaky Russian grandmas. My wife had managed to make this slightly sinister location into a home for our small family, and a place of hospitality for other westerners sharing our adventure. I can’t now work out exactly when our Christmas dinner was supposed to be in 1990, because it was delayed and disrupted so many times as I and our guests had to repeatedly rush off to the telephone.

The Congress of People’s Deputies was in session and for the first time was functioning quite like a real parliament, and December 25 was just another day of unpredictable events and news. It was sandwiched between the melodramatic resignation of the foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, warning that dictatorship threatened, and the appointment of the sinister clown Gennady Yanayev as vice president. Shevardnadze was right to worry. A few months later Yanayev, drunk and trembling, would lead a Stalinist putsch. The fall of the Soviet Union seems inevitable now, but it didn’t then. Communist spite and violence were seething among the old guard of the KGB, our neighbors. Some would kill rather than let go of power. A few days later I would see horrible violence in Vilnius as the old Bolshevik monster showed it was not yet dead.

But in the midst of it we made a “lighted island of happiness and peace,” as Winston Churchill described another embattled Christmas long ago. The tree was easy — we simply converted a scrawny Soviet New Year tree with decorations brought from home and somehow got past the Soviet customs.

But the meal was the special, sentimental triumph. Moscow in 1990 was still the capital of an Asian and Caucasian empire. My wife had become skilled at negotiating in the gangster-haunted markets of Moscow, most of them near one of the great railway stations which were the gateways to the USSR’s colonial dominions in the Caucasus, on the Black Sea and stretching into central Asia. The people who sold at these markets were generally the people who had grown and prepared the produce, and travelled hundreds of miles by train to make a small profit from privileged Muscovites.

For the Christmas pudding, she found delicious dried fruits from the shores of the Caspian Sea, and dark fierce brandy from Armenia. These were the old-fashioned, more potent tastes of a less modernized world, such as our grandparents might have known. It was beyond doubt the best Christmas pudding I have ever eaten. Georgia supplied the wines — the wistful red Mukuzani, unlike any western vintage, and the astringent white Tsinandali. Soviet “champagne,” which at the time I used to joke was a form of chemical warfare, was only for the courageous or the desperate. Once had been enough for us.

And of course there was no turkey. Instead there was the goose. My wife, after failing to find anything appealing in one of the markets, had been walking down a side street nearby when she found the old woman in black, a nervous peasant with one thing to sell. No doubt she was trying to avoid paying protection money to whatever mafia controlled the actual market building. She looked as if she might have some magic beans available if asked nicely, but the goose was magical enough. They quickly concluded with a perfect bargain in which the woman received far more roubles than she had dreamed of, and we in turn could not believe how cheap it was. I have never in my life eaten a more delicious goose, like a giant wild duck, not greasy as western geese are, tasting as if it had been reared in a snowy forest — because it had been.

The dark afternoon and evening still glitter in my memory. Outside, the brown slush and dirt of Soviet modernity, and the yelling, fist-pounding politics of an evil state (and it truly was) flailing in its death agony. Inside, a distillation of all that was good in our culture and theirs, and crowned with a small and defiant remembrance of the greatest enemy tyranny ever had, Our Lord, Jesus Christ.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.