I first came to Russia as a traveling English literature lecturer in the late 1990s. This wasn’t a job given to me but one I’d devised myself, sending off snail-mail begging letters to different university departments all over the former Soviet Union — Barnaul to Minsk — outlining my services and occasionally, weeks or months later, being taken up on the offer.

With a backpack full of books, I’d catch a train — sometimes a days-long journey — to the next destination, where I’d be given a list of students to teach, a guided tour of the city and three weeks in a student hall of residence. Here cockroaches could outnumber humans 100-1, but there was always a bottle going round and someone with a guitar to supply entertainment in the evenings. And, oh, the conversations…

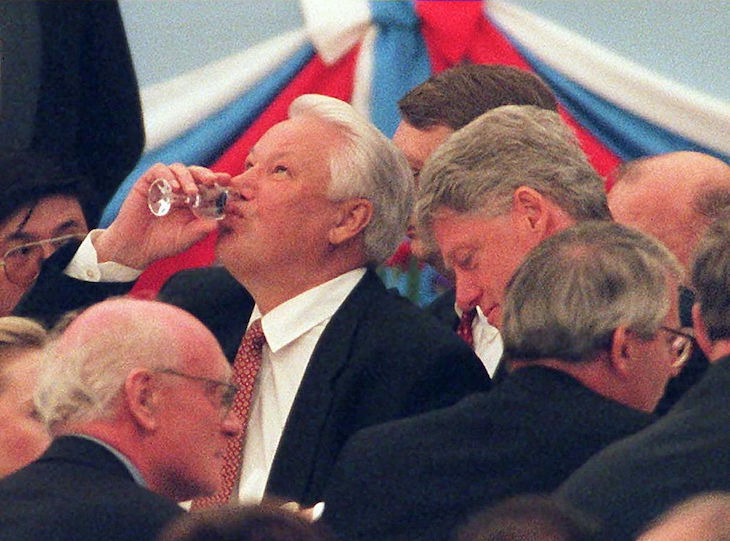

Russia then was a different country. Under Boris Yeltsin there was rampant crime and economic crisis, but also free speech and, among the young, an optimism about where the country might be heading. Stalin was out, dreams of democracy were in, but aspects of the Soviet way of life, if not the system, endured. The ancient Russian religion of vodka and reading was, pre-internet, in healthy shape. Most people still smoked, didn’t have cars and hadn’t yet discovered consumerism as a religion. Food shops, with their pyramids of tins in the window, were exercises in austerity — I lived for about a month on bread rolls, paprika-flavored cheese triangles and dried figs. It was also virtually impossible to get a decent cup of coffee anywhere. In one café a waitress assured me flutteringly that yes, yes, of course there was real cappuccino, and sparked up a vast, noisy coffee machine to reassure me. I caught her a few seconds later hunched behind it, spooning Nescafé into a mug.

My most memorable stint was in Volgograd, during the 1999 NATO bombing of Belgrade, undertaken in response to Serb leader Slobodan Milošević’s persecution of the Kosovan Albanians. Most of the Russians I met were instinctively pro-Serb (fellow Slavs, fellow Orthodox) and vehemently anti-West.

“Kill Americans” said graffiti on one wall, and “Americans, please consider why you are hated all over the world!!!” Much of my time was spent coming under attack for Tony Blair’s “warmongering” and being asked by Russians how Britain, the US and their allies could possibly attack an innocent country, the clear implication being that the Russians themselves could never do anything like this.

Under Boris Yeltsin there was rampant crime and economic crisis, but also free speech

But largely, anti-American feeling was simmering and futile, the natural resentment of those who’d lost the Cold War and felt the world going unipolar. At a student summer-revue, I attended, there were endless, feeble jokes about Clinton and Monica Lewinsky, at which the students laughed gleefully, savouring the moral high ground. On television, shots of damaged Belgrade were intercut with footage of the Holocaust, and there was much talk of World War Three. This, says Jade McGlynn in her book Russia’s War, was the beginning of Russia’s obsessive fear of NATO, which has borne such bitter fruit in the last few years.

But it was difficult to forget war in any case in Volgograd. As Stalingrad (its previous name) it had suffered horrific fighting in World War Two, the bulk of the city being destroyed. Volgograd was festooned with war-memorials, culminating in Mamaev Kurgan, with its 280-foot statue of Rodina Mat, Mother Russia. At the time it seemed a powerful monument to the country’s wartime sacrifices, though later, after February 2022, it hinted at a grisly entitlement as well. Even in 1999, nationalism was coming back in Volgograd. The history departments were said to be full of young men dressed in black, crying “Russia for the Russians!” and beating up the odd hapless foreigner.

My students there were among the best I ever taught. They boiled down to a trio of young men, Seryozha, Lyosha and Andrei. These three hung out together 24-7, ending each day lying cheerfully drunk in one or other of their flats, reciting bits of Castaneda or Kurt Vonnegut (a particular favorite) to each other, or blissing out on Bowie and Leonard Cohen, analysing the lyrics like ancient Sanskrit. They hoovered up Kieslowski and Kusturica on VHS, fell in love with the same girls, schemed about the works they’d create in their glorious futures and the countries they’d visit.

We spoke a lot about their leader, the almost permanently drunk Yeltsin. Although they were effectively Yeltsin’s children, their outlooks formed during his brave stand against the attempted hardline coup of 1991, the promise of those early days had taken a dark turn into the crime, financial crisis and first Chechen War which had followed. Many of our conversations, in early summer 1999, were about who would likely replace him. Yuri Luzhkov, mayor of Moscow? This was quite possible, they said — Luzhkov was bald, and since the revolution, leaders with full heads of hair had invariably been succeeded by slapheads.

Others thought it might be Primakov, the lumpen prime minister, or Boris Nemtsov, Yeltsin’s charismatic, approachable young protégé (later assassinated in the shadow of the Kremlin). What everyone agreed was that Yeltsin had become a national embarrassment and had to go. The depictions of him on Kukli, Russia’s answer to Spitting Image, had become ever more grotesque. Crueler still was the way news companies filming the Duma would, when Yeltsin was paralytic and incapable of speech, simply let the camera hover on him for long, incriminating minutes.

The history departments were full of young men crying ‘Russia for the Russians!’ and beating up the odd hapless foreigner

I met these three students at their youngest and most dagger-sharp, but in the following years they’d have widely different fates. Seryozha — Jewish, charming, with beautiful hands and sensitive perceptions (he was a poet) — moved to London and started making art-films. Lyosha, acerbic and erudite, a dead ringer for Malcolm McDowell in Caligula, became an interpreter in Russia’s weirder, furthest-flung locations and a disaffected, religious Putin-hater. Lyosha was the instinctive lawyer among the three, with a strong belief that treaties, respect for borders, and the rule of international law ought to matter. Putin’s antics in Georgia and Crimea, needless to say, appalled him.

The saddest of all stories was Andrei’s. Visibly less mature than the others (his grandparents still buttoned him into his overcoat), he had an early, tragically failed marriage, slid into paranoia and converted to Islam. When war broke out in Syria, Andrei — as reported, incredibly, in the UK Daily Express — volunteered to fight for ISIS, taking his second family with him. Their bodies were never found.

Like Lyosha, I look back on that period of freedom — pre-internet, pre-cell-phone, pre-ties and responsibilities — with a certain nostalgia. For all of us, all young men in our twenties, the future seemed full of dazzling possibilities.

Two months later, Boris Yeltsin made an unknown KGB operative, one Vladimir Putin, prime minister of the country. Within a year he would be president. It was the end of the 1990s, the end of the millennium, and the end of that Russia too. Things fall apart, you might say. Or, as their beloved Kurt Vonnegut would have put it, “so it goes.”

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.