In May 2021, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reported that the remains of 215 children had been found buried at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation band had confirmed the story, they claimed, quoting Chief Rosanne Casimir. “To our knowledge, these missing children are undocumented deaths,” she said. “Some were as young as three years old. We sought out a way to confirm that knowing out of deepest respect and love for those lost children and their families, understanding that Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc is the final resting place of these children.”

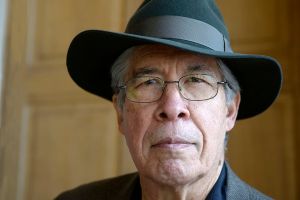

The outcry was enormous. Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, then-director of the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre at the University of British Columbia, told the CBC she “had questions about how these children died given the rampant sexual and physical abuse documented in residential schools.” (Turpel-Lafond resigned earlier this year after her “Indigenous background” was called into question.)

“This is absolutely heartbreaking news,” federal minister of Indigenous Services Marc Miller tweeted, adding that he had spoken to Casimir “to offer the full support of Indigenous Services Canada as the community, and surrounding communities, honor and mourn the loss of these children.”

It would have been a horrifying story — if it were true. But no remains had been discovered. No graves were discovered. There had been no excavation. Rather, ground-penetrating radar anomalies had been detected, which, for all we know, could have identified “2,000 feet of trenches in a long-forgotten septic field installed in 1924,” as one researcher suspects.

But stories of mass “unmarked graves” discovered at the site of a residential school for children proliferated nonetheless. “‘Horrible History’: Mass Grave of Indigenous Children Reported in Canada,” announced one New York Times story. In June, it was reported that 751 unmarked graves had been “discovered” at the former Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan. The Times recounted that these remains were of “mainly children.”

The implication was dark: that countless Indigenous children had been killed at residential schools in Canada, then buried stealthily in “unmarked graves.” The public, the media and the government responded accordingly.

Orange Shirt Day, an offshoot of Canada’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, with the added tag line, “Every Child Matters,” was implemented in schools across the country. Flags were lowered to half-mast at public schools, universities and federal buildings “to honor the 215 children found in an unmarked mass grave at the former Kamloops residential school.” That year, calls to cancel Canada Day went viral, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the day should be one of reflection, rather than fireworks, suggesting the country think of “those for whom it’s not yet a day of celebration.” Indeed, several towns and cities canceled their annual festivities, including British Columbia’s capital, Victoria, encouraging people to consider “what it means to be Canadian in light of recent events.” Hundreds of masked Vancouverites gathered for a Cancel Canada Day rally on July 1 at Vancouver’s Art Gallery. In Winnipeg, protesters toppled statues of Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II, chanting “no pride in genocide.” Churches were vandalized and burned to the ground, most on Indigenous land — places of worship and healing for these communities. A wooden church named St. Ann’s near Hedley, British Columbia — where members of the Upper Similkameen Indian Band had been gathering for more than a century — was razed, as was the Sacred Heart Mission Church, which had served the Penticton Indian Band since 1911.

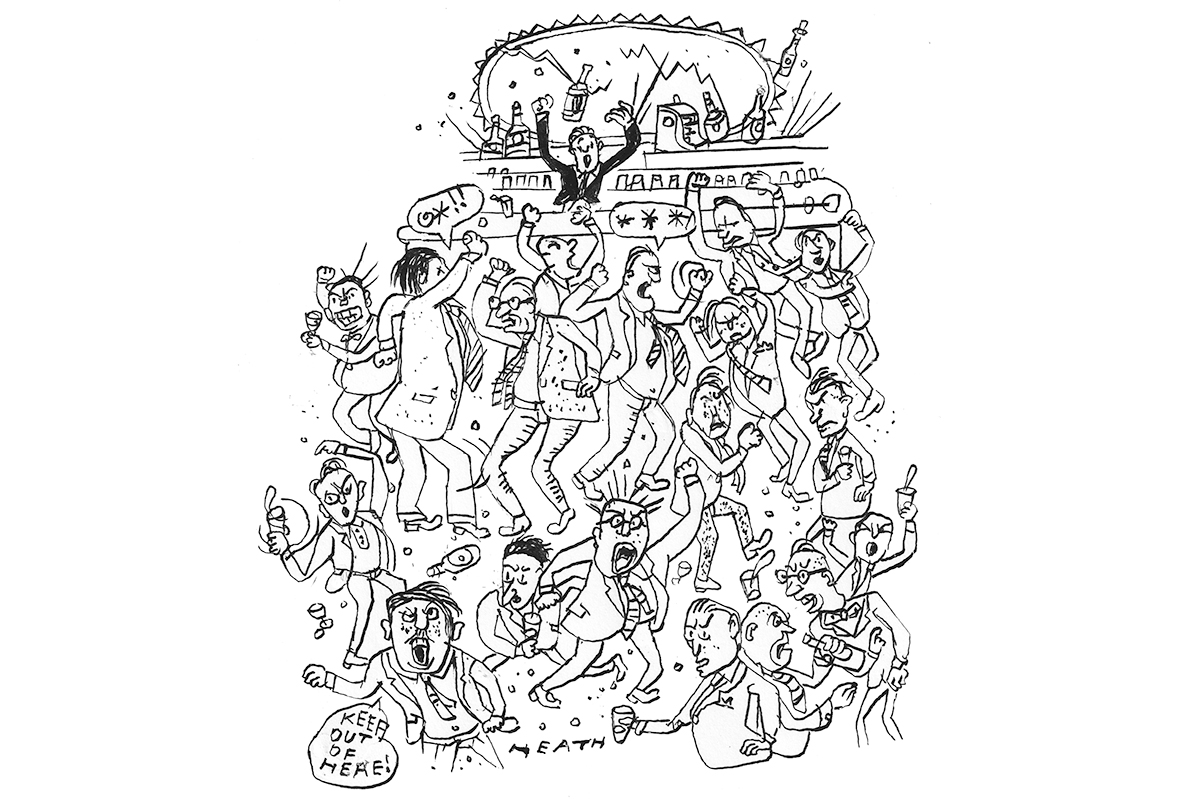

Not long after, Trudeau visited the Cowessess reserve in Saskatchewan, photographed kneeling and holding a teddy bear at the site of the former Marieval residential school. “It is shameful that here in Cowessess, and across the country, children died because of the policy of residential schools,” he said.

“Canada must acknowledge the truth. We must also understand the truth.”

But we didn’t have the truth.

There had been no discovery of “mass graves” full of Indigenous children at residential school sites in Canada.

As reported by Terry Glavin, one of the few journalists in Canada attempting to get this story right, the grave site Trudeau visited for his photo shoot was a Catholic cemetery — a community cemetery — that has long been known to the Cowessess people. “Children and adults, Indigenous and settler, were buried there, going back generations,” Glavin explained.

The language of “unmarked graves” implies something nefarious, as does the inclusion of “Indigenous children” in every headline. Progressive Canadians ran with the implication, posting such messages as, “If you celebrate kkkanada day.. you’re probably anti-Indigenous.” Indigenous activist and writer Rebecca Nagle tweeted: “Another mass burial site of children killed at residential schools has been identified in Canada. Many people want to ‘move on’ from our history. When the victims of that history haven’t even been laid to rest.”

In August 2021, Assembly of First Nations Grand Chief RoseAnne Archibald told the BBC’s Hard Talk program that these were “crime scenes,” as “hard proof” had been revealed through ground-penetrating radar that “crimes had been committed against First Nations people.” Archibald went on to describe residential schools as “institutions of genocide” that were “designed to kill,” saying only now were we “beginning to see the truth about what these institutions did,” which was, according to Archibald, that “1,600 little children — little ones — innocent children… [were] recovered so far.”

Again: to date, no excavations at any of these sites have turned up human remains.

Doubtless, terrible things happened to some of the kids sent to residential schools in Canada. Past reports have been grim, with stories of sexual and physical abuse. But can there not be dark truths without reporting mistruths? Why must those who report on the situation accurately, such as Glavin, be labeled a “genocide denier” and a “residential school denialist”? It’s one thing to trust shocking headlines, but it’s another to maintain the conceit even after the story has been debunked.

Just a few months ago, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights tweeted, “It has been two years since the remains of 215 children were discovered in unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School.”

Last week, CTV News reported that a Saskatchewan First Nation says it found seventy-nine suspected child grave sites and fourteen potential infant grave sites, also via ground-penetrating radar. Will excavating those sites also turn up nothing?

The reality, apparently, is less appealing than genocide.

This is common nowadays. But why would you want it to be true that countless Indigenous children were killed, then tossed into unmarked graves across Canada?

Canadians like to think of themselves as good, kind, inclusive people who are viewed by the rest of the world as such. But that’s not the reputation we’re developing. Rather, the world is beginning to see Canada as an example of “woke” gone wild — a clown car careening off the rails into the arms of a shop teacher wearing Z-cup prosthetic breasts.

The good news is that the truth is out there. The bad news is that speaking it may make you unpopular.