The halcyon days of 2018 seem very distant. Two years ago, North Korea sent a delegation to the Pyeongchang winter Olympics; three summits took place between the leaders of the two Koreas; President Trump and Kim Jong-un wined, dined, and produced what John Bolton terms — in his latest book — a ‘substance-free communiqué’ in Singapore. Now the era of newfound warm relations between Pyongyang and Washington seems to be over.

The ‘permanent and stable peace regime on the Korean peninsula’, to which the two Koreas committed in April 2018, is anything but fulfilled. And if recent events show, relations are in danger of deteriorating rapidly. While Kim Jong-un is still at the helm of North Korea, his sister, Kim Yo-jong, is playing a growing role, as mediating force between the party and military, and taking a firmer hold of inter-Korean affairs. She may not have been designated as the Great Leader’s successor — at least for the time being — but her actions and words seem to have garnered her brother’s approval.

Pyongyang had high hopes that South Korea’s leader Moon Jae-in would offer better relations through economic cooperation. It hoped, too, that its neighbor might compel Washington into removing economic sanctions imposed upon the state. In North Korea’s eyes, South Korea has achieved neither of these aims. So the North’s intensification of brinkmanship is one means to induce South Korea to the negotiating table. But will it work?

The recent distribution of anti-DPRK leaflets by South Korean activist groups across the inter-Korean border only furthered the North’s anger at the South. The Panmunjom Declaration, signed by the leaders of the two Koreas in April 2018, forbade such activity. From the vantage point of Pyongyang, if Seoul cannot keep its pledges, there is no need for Pyongyang to reciprocate in good faith.

The destruction of the inter-Korean liaison office at Kaesong last week is a much more radical step. The attack also shows that North Korea’s vitriolic statements are not just hot air. Kim Yo-jong, whose pronouncements on North Korean state media are becoming evermore numerous, warned earlier in the month of the liaison office’s precarious survival. True to her word, it has now been blown up. The rise of Kim Yo-jong within the North Korean regime also points to how it is not just Kim Jong-un who will deal with the North’s relations with South Korea and the US in the future. And this is not necessarily good news for the world.

It’s worth remembering, of course, that North Korea has plenty of domestic troubles of its own. So intensifying provocations with its neighbor offers a helpful diversion away from what is happening within the country. The regime’s claims that the state is free from the ravages of COVID-19 are highly dubious, and the declining health of Kim Jong-un raises questions about debates within, and between, factions in the Workers’ Party and the military elite. The North Korean economy continues to be hit by sanctions, as well as the damaging effects of reduced Sino-North Korean trade owing to coronavirus. With the United States renewing sanctions on the DPRK only last week, sanctions relief — particularly targeted on the North Korean economy — is becoming a distant dream for Pyongyang.

[special_offer]

Calls for calm and restraint on the Peninsula were echoed by China and Russia, with the European Union condemning Pyongyang’s recent actions, which the North rapidly rebuffed. The US response was somewhat subdued, but Washington has enough on its plate at present. With the presidential election drawing near, and COVID-19 yet to be contained domestically, a likely but unfortunate scenario is that there will be few, if any diplomatic overtures from Washington to Pyongyang between now and November.

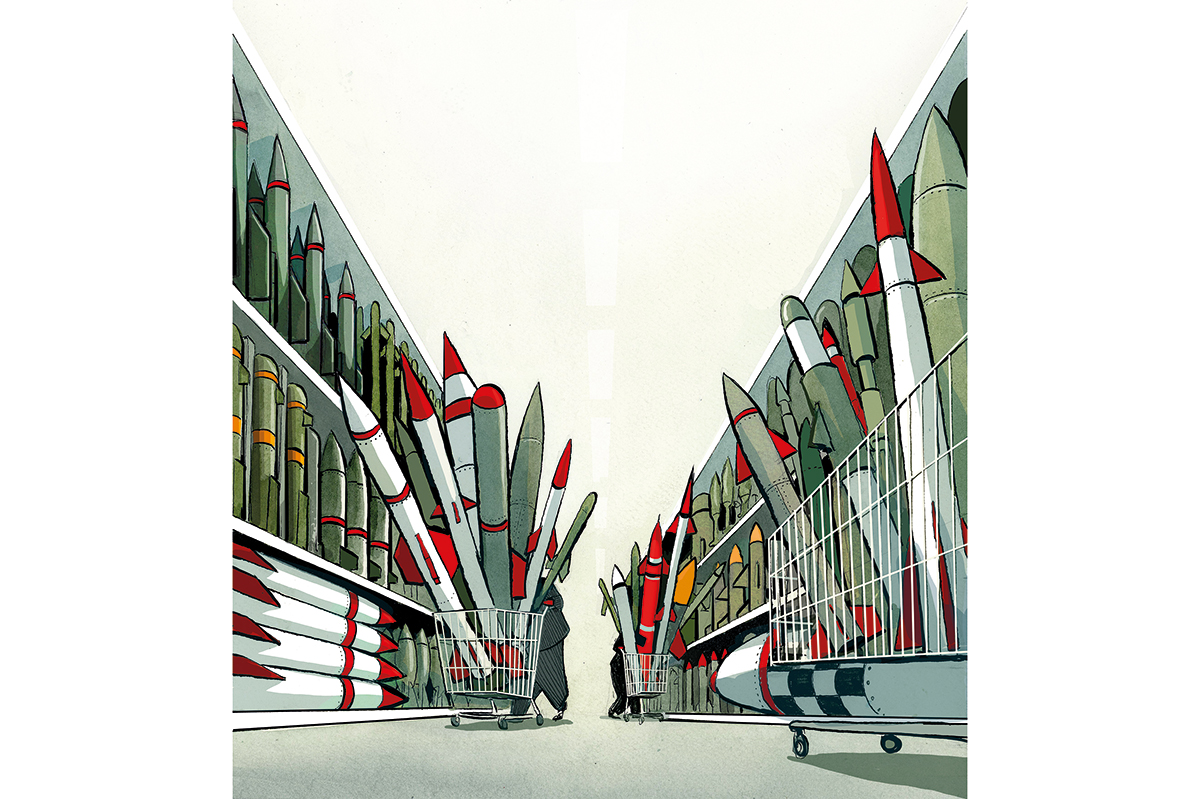

The South Korean administration stressed how it would not tolerate ‘insults’ and ‘aggression’ from the DPRK, but the same goes for the North. Pyongyang threatened to continue its retaliations ‘far beyond imagination’. One of the next maneuvers is likely to involve some kind of military action — if Kim Yo-jong’s past warnings are anything to go on — as the North adopts the mindset that any prior commitments with the South, such as military agreements, are not worth upholding. Earlier last week, Pyongyang threatened to shower Seoul with ‘leaflet bombs of justice’ comprising propaganda denouncing the South Korean administration. Nevertheless, the possibility of worse behavior, such as short-range missile launches, should not be ruled out. The world has not yet seen the ‘new strategic weapon’, mentioned by Kim Jong-un in tormenting the international community at the end of 2019.

North Korea is the ‘land of least lousy options,’ according to the former US National Security Council adviser Victor Cha. He’s right. North Korea’s quest to preserve and develop its nuclear program, while violating the human rights of its citizens leads to an impossible question: how should a world wracked by coronavirus deal with North Korea? Unfortunately, there is no good answer.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.