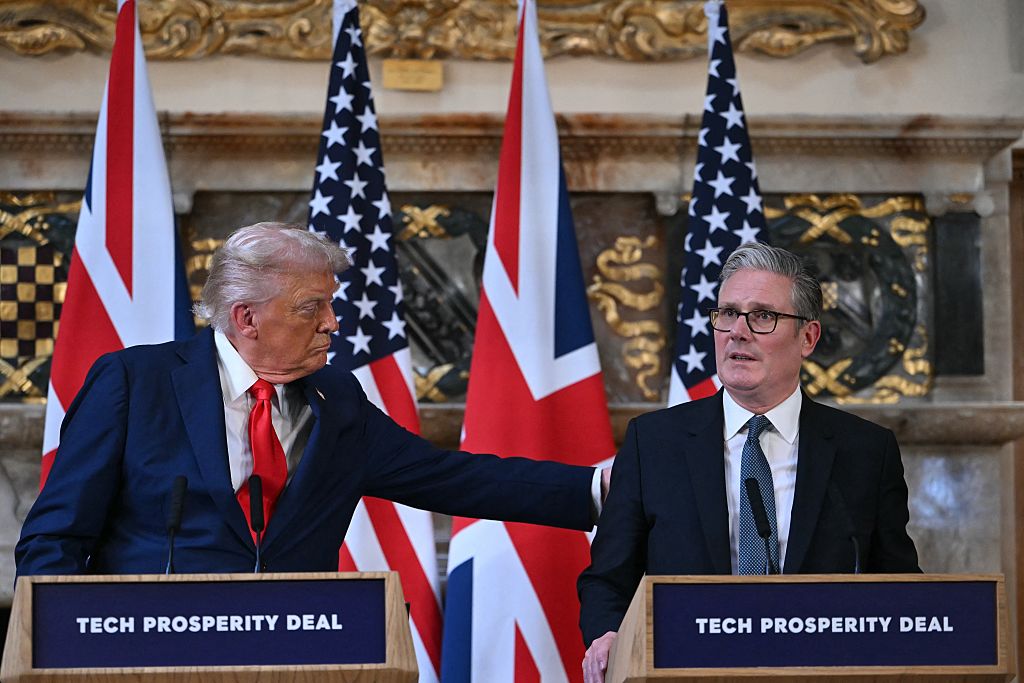

There’s still a month of the Labour leadership contest to go but most British Members of Parliament have already concluded that Keir Starmer will win. The shadow Brexit secretary has led in every category so far: MPs, unions and local parties. As the contest enters its final stage, polling suggests the membership agree and Sir Keir will sail through. His closest rival, Rebecca Long-Bailey, is now seen as a ten-to-one outsider. One bookmaker is already paying out on a Starmer victory.

But if the race seems all but over, the conversation about what he’ll do as Labour leader is very much on-going. Is he the leader that the party’s moderates have craved to stand up to the hard left — or a vessel for continuity Corbynism?

So far, he has tried very hard not to say. He has managed to attract supporters from both sides of the party, parading a reputation for pragmatism to win support from the center, while using selective cases from his legal career to present himself as a champion of left-wing causes. Most of these cases he lost, but to today’s Labour party this isn’t such an issue.

His campaign team has tried to balance the various Labour tribes. It includes Simon Fletcher, who has made a career working for socialist politicians, such as Ken Livingstone at City Hall. From the right of the party he has Matt Pound — formerly of Labour First, a Corbynskeptic group that has clashed with Momentum.

His supporters range from un-ashamed Blairites, such as Ben Bradshaw, to Laura Parker, the Momentum organizer, and to the now-retired Corbyn cheerleader Paul Mason. Sir Keir has spoken frequently in the campaign of the need for unity and to move past the internal conflicts of recent years. But there’s a sense that sooner or later, he’ll have to favor one faction at the expense of the other.

‘Keir is a blank page,’ admits one MP backing him. ‘No one knows what he will really do. We’re all just hoping it will be close to our own politics.’ Those hoping for early clarification may be left disappointed: Sir Keir and his team see his leadership as a five-year project. Expect some strategic ambiguity in the early stages. They accept that it will take years to get the party to where he wants it to be.

Some changes can be made quickly. He has already promised to give roles to his leadership rivals Lisa Nandy and Rebecca Long-Bailey (although he has drawn the line at Jeremy Corbyn).

‘How many of the old shadow cabinet stay in depends on the size of his lead,’ says a party source. ‘The bigger the lead, the bigger the change.’ Expect fresh faces to be included as part of a bid to show the party is moving forward. Bringing back those who wouldn’t serve under Corbyn would also be a way of signaling that the party has changed.

Next: party organization. There will be a move to oust members and supporters guilty of anti-Semitism. In theory, this ought to be uncontroversial, but given how high tensions run in the party, there’s a view that the EHRC investigation into allegations of anti-Semitism within Labour could offer Starmer the necessary cover to take drastic action. The results of this are expected after the May local elections.

Corbyn allies are still running the Labour machine — Jennie Formby as general secretary, for example. Sir Keir is under pressure to clear them out. This will be an uphill task. There are already reports that the hard left is digging in and will even install allies in key roles in anticipation of his arrival.

An easier task ought to be found in his team’s hopes to establish an efficient media operation to take advantage of the Tory policy of boycotting certain programs. When, for instance, Priti Patel was under pressure this week, a sharp Labour machine would have been quick to attack and make hay. Since the 8.10 a.m. slot on BBC Radio 4’s Today program seems to be up for grabs for the foreseeable future, it’s an open goal. It’s also viewed internally as crucial, given that the 80-strong Tory majority makes Labour victories in the Commons unlikely.

In parliament, Sir Keir will try putting forensic lawyerly pressure on a prime minister who dislikes it. But what issues will he be pressing? It’s thought he will position himself to the left of Ed Miliband. Ten pledges he made this month included a vow to keep Corbyn’s policy to abolish tuition fees — as well as a program of mass nationalization and a ‘Prevention of Military Intervention Act’ to end illegal wars.

‘He didn’t need to do it,’ says one concerned supporter. ‘We’d been told he wasn’t going to do policy because he didn’t want to be wedded to anything.’ Others complain that it was a very Gordon Brown thing to do: make a rash decision in response to something your rivals are doing.

Brown might not be far away. The two men are still close (it was Brown who hired Starmer as director of public prosecutions) and often speak in private. Starmer has also sought advice from Sadiq Khan, Labour’s most senior elected representative.

It’s this appetite for winning that could separate him from Corbyn. Those who have worked closely with him say he takes an interest in polling in a way that Corbyn never did. ‘Keir wants to be prime minister,’ says a Labour source. ‘He’s focused on that in a way Corbyn and even Miliband weren’t. He will react to the country and its needs, rather than just going on ideology.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.