One of the quietly profound pleasures of travel is renting cars in unusual locations. I’ve done it in Azerbaijan, Colombia, Syria and Peru (of which more later). I’ve done it in Yerevan airport, Armenia, where the car-rental guy was so amazed that someone wanted to hire a car to drive around Armenia that he apparently thought I was insane. Later, having endured the roads of Armenia, I saw his point – though the trip itself was a blast.

Recently I rented a car in Almaty, Kazakhstan, where they were slightly less surprised than the Armenian had been, but nonetheless gave me lots of warnings and instructions, chief of which was: “Don’t rely on Google Maps, it doesn’t work out here.” As soon as I was told that I felt my heart lift, because it meant there was a fair chance of getting lost – and if I like renting cars in remote spots, I love getting lost, anywhere. And yet sadly, as technology gets ever more efficient, it becomes harder to end up completely clueless as to where you are.

Before the advent of Google Maps, GPS, Starlink and the rest, getting lost was a doddle. I’ve done it everywhere. Africa, Asia, the Americas, the Antarctic peninsula (in a storm). I’ve been really lost in south London without a map.

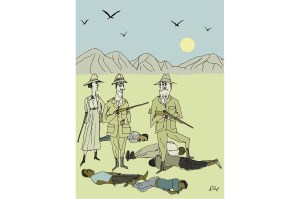

Amid this lexicon of lostness, some adventures still stand out. In Peru, while researching a thriller in the gray, weird, eerie Sechura desert north of Lima, I went looking for an ongoing archaeological dig, the excavations of which have revealed the unsettling sacrificial rites of the 2nd- to 9th-century Moche people, known for their incestuous sexual practices, culminating, it is thought, in the strangling of their own teenage children.

So it was that I got completely lost in the dusty scrub, failed to find the dig, panicked for an hour, then, as I finally worked out where I’d parked, I felt a scrunch underfoot. I was walking over an eroded adobe Moche pyramid and many pieces of Moche pottery, depicting their fanged Tarantula God. If I hadn’t got lost, I wouldn’t have those haunting shards on a shelf in my apartment today.

Sometimes getting lost can be good because it revives your faith in human nature. On a later trip to upland Peru I got lost in a forest, took several wrong turnings in my car, went entirely off-road and ended up stuck in knee-high sand, wheels spinning uselessly. Running out of ideas, I looked in my guidebook. All it said was that the forest in which I was marooned was “known to be dangerous and several tourists have been murdered here.”

A few minutes later, a local passed me on a moped. He didn’t murder me. Instead, he went to his village, where he recruited half a dozen laughing friends who helped me get my car unstuck and refused the money I offered. They did it because most people around the world are really nice, given the chance. Getting lost teaches you that.

On some of my misadventures, the thrill comes from the sheer danger of being alone somewhere remote. That was the case when I drove the Fish River Canyon in Namibia. The baboons were fun and the birdlife was vibrant but then I realized I had no idea where I was, and I might be the only human for 30 miles. But then I thought, heck, it’s a canyon: all you can do is drive to the end. I did. It was fine – and a buzz I won’t ever forget. Yes, breaking down would have been a nightmare, but that didn’t happen.

Other times, lostness is aesthetically pleasing. One of the best things you can do in Venice is go there in winter (and dump your phone), then start aimlessly wandering away from St. Mark’s Square at night. Soon you will be lost in a maze of damp calli and silent piazzette and chilly black canals, with an invisible gondolier plashing in the mist and the noise of a bar always just around the corner. You almost swear you can see the ghost of Byron, or wicked little ladies in scarlet coats. Spellbinding.

But getting lost is not always good. I don’t recommend getting lost in Alphabet City, New York, in the mid-1980s. Try not to get lost any time in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Or Mexico in general. Nonetheless, it is a vital part of the human experience; if we forsake it, we will, ironically, lose something precious. So here’s my advice – and the final lines of a memoir I’ve just written about my absurdly wandering life: wherever you are in life, get lost. It’s the only way to know if you truly want to be found.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply