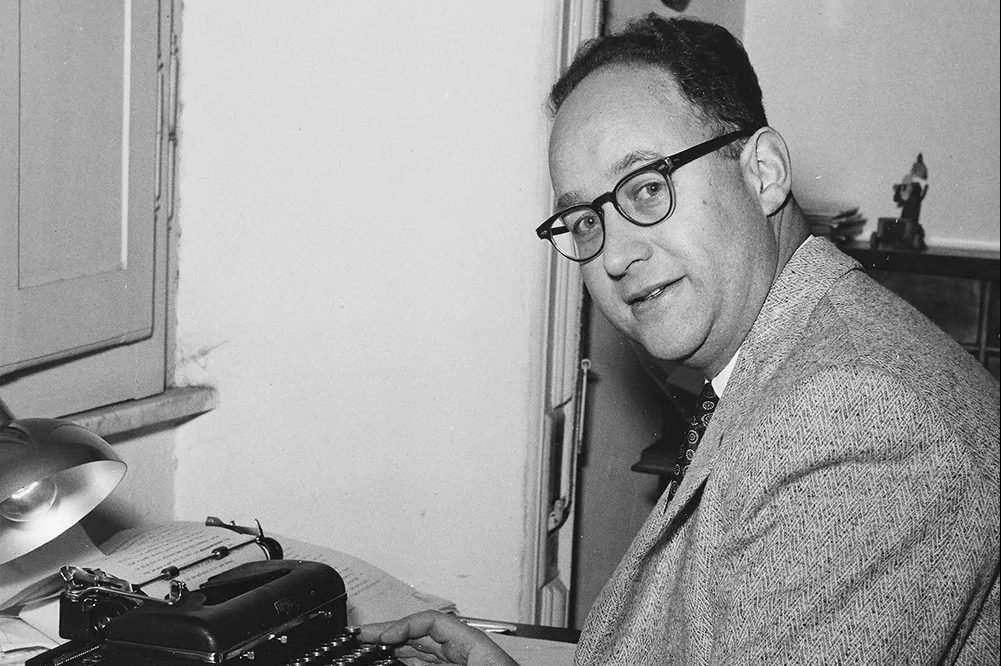

Jordan Peterson has left his professorial post at the University of Toronto. He announced his departure with characteristic blunt honesty in Canada’s National Post.

Peterson first came to my attention in 2016, as he did for many, for his refusal to bow to demands to use novel pronouns preferred by the transgendered. For this, he was denounced as a bigot, his university threatened his career, his speaking events were disrupted, all done under the cloak of civility: all transgender people wanted was respect, to be addressed as who they were. How dare Peterson be so uncivil?

Lost in the shrieking winds that enveloped him was his basic point: it’s no longer civility when it’s backed up by the force of law. Civility is no longer on the table when you can be thrown in jail for an opinion. The proliferation of pronouns at the bottom of email signatures everywhere is silent testimony to the iron fist inside the velvet glove.

To an (ex-) academic like me, the most dismaying thing about the Jordan Peterson saga (which will not end with his departure from UT) was the desertion by his fellow academics. Peterson was a vigorous and insistent defender of the transcendent value of the academy: as a bastion dedicated to the free, and freewheeling, play of thought and debate. Nearly all of us who chose the academic life were attracted by the promise of untrammeled intellectual freedom.

It’s easy to dismiss that as moral narcissism, as many did with Peterson. It is, in reality, the only rational basis for the academy’s existence. Without that foundation, universities become just another feeder at the public trough. Surely Peterson’s colleagues would know that, and would rise to the defense, if not of the man himself, at least of the principle? Instead, it was his colleagues who seemed the most eager to plunge the sword into his neck.

Whether we choose to acknowledge it or not, our great universities are being pushed into crisis by a regnant illiberal ideology. As John Ellis has pointed our in the Wall Street Journal, this illiberal ideology has been working its way into our institutions for a very long time, advanced not by any adherence to the Enlightenment ideals of the academy, but by the patient and unrelenting pursuit of political power. It has been remarkably successful, advancing slowly behind the cloak of benign and soothing names: “woke,” “DEI” (Diversity, Inclusion, Equity), “social justice,” “environmental justice,” etc.

The takeover is now virtually complete. Jordan Peterson is the latest casualty. Amy Wax at the University of Pennsylvania is likely the next in line.

Academics who still hold the university’s Enlightenment ideals to heart find themselves forced to make a very hard choice: stay and fight the good fight, or leave and fight from the outside. Peterson justified his choice starkly: he could no longer make a moral case to stay, because doing so would mean forcing himself, his students, and his colleagues to acquiesce to a lie. So he left. Others, like Dorian Abbot, are choosing to stay and fight. Good for him. Both choices are worthy of our praise, but we should be clear why: it is not the choice itself that is praiseworthy, but the courage that went into making it.

Three years ago, I had to make the choice myself. The academic culture where I found myself at the end of my career bore little resemblance to the culture when I began. My choice was to leave. I made it privately; it was accompanied by no furor. Since then, I have spoken to many colleagues, both retired like me and still early in their careers, who express similar feelings and forebodings as mine. Like me, they express their concerns privately, but not publicly. Their motivations run the gamut. Some just want to be left alone. Some want to stay focused on “tending their own gardens,” as Voltaire expressed it. Some want just to hang on until retirement. Some hope this is a temporary madness that soon will pass.

I have bad news for us all. The academy has changed fundamentally, and with each passing year there are fewer and fewer who can restore it.

The change is not irrevocable, though. Totalitarian states, which our universities are coming to resemble, are kept in power by the skillful use of lies and pressure to conform. Any unapproved thought that pops into someone’s head is a threat to the state. If the person can be made to believe that no one else harbored the same thoughts, the regime’s power is secure. That is the purpose of propaganda: not to tell lies, but to get everyone to acquiesce in those lies.

For the communist regimes of eastern Europe, all this came unraveled in the late 1980s, through something known as a preference cascade. Once people began to see that they were not alone in their doubts, that many others had the same privately held beliefs, the totalitarian regimes collapsed catastrophically. The most spectacular example of this was the end of the Ceausescu regime in Rumania in late 1989. While Ceausescu was delivering a public speech, the gathered crowd simply stopped listening, the disbelief rippling visibly. People realized suddenly that nearly everyone else in the crowd knew they were hearing lies, and that was the end of Ceausescu and his regime. Four days later, he and his wife were executed by firing squad, undone by a cascade of disbelief.

Will the salvation of the university come in a similar preference cascade? Will people simply stop believing the lies, about race, about gender, about the soothing tropes of diversity, equity, and inclusion? At this point, it’s touch and go.