Sloppy Joe Biden may face strong political headwinds with just seven months to go before the first presidential primary, but at least he’s in good company. Assessing the Washington landscape in mid-June 1963, when John F. Kennedy set off on a European tour designed to bolster not only the NATO alliance but his own poll numbers, the British ambassador David Ormsby-Gore cabled back to London:

He will be leaving behind a disquieting domestic situation, [with] economic troubles to the fore… The Negro leaders are beginning to talk about large scale civil disobedience on a nation-wide basis… Moreover, the racial crisis is causing new difficulties for [Kennedy’s] legislative program… There has been a marked lack of congressional enthusiasm for the president’s trip.

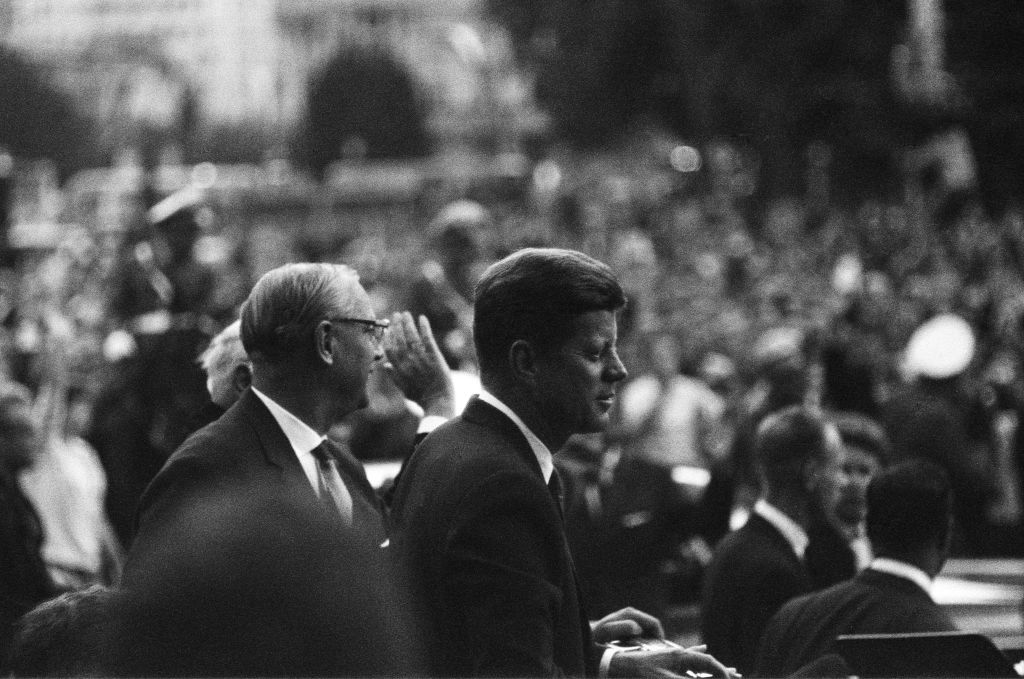

This was the atmosphere in which, sixty years ago, Kennedy set out on a journey that combined the qualities of high-minded statesmanship with those of a slightly chaotic street party. The Berlin Wall had appeared less than two years earlier, a crisis followed by the standoff over the installation of Soviet missiles just ninety miles from US shores in Cuba. By the early summer of 1963 it seemed that superpower confrontations up to and including the threat of thermonuclear warfare were the rule, and prolonged periods of international stability the exception.

On June 23, Kennedy assured a welcoming crowd in Cologne, “The United States is on this continent to stay. So long as our presence is desired and required, our forces will remain.” Three days later, more than a million people came out to hear Kennedy speak in a rock concert-like atmosphere at West Berlin’s city hall. He was cheered deliriously when he delivered the lines for which his trip is best known today:

“Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was civis romanus sum. Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is Ich bin ein Berliner… All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’”

The parentage of the phrase itself is still disputed. For years, the president’s speechwriter Ted Sorensen and his local interpreter Robert Lochner were thought to have had a hand in the line. But Kennedy’s claims to authorship are bolstered by his remarks, apparently original, at a May 1962 reception in New Orleans: “Two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was to say ‘I am a citizen of Rome.’ Today, I believe the proudest boast is to say ‘I am a citizen of the United States.’” Perhaps in time Kennedy would have gone on to adapt the aphorism for use in towns and countries around the world. In any case, it was one of the defining moments both of his presidency and the Cold War, even if “ein Berliner” happened to be local slang for a jelly donut. The Berlin audience’s response was so effusive that the German chancellor Konrad Adenauer, surveying the arms stretched aloft below him, asked sotto voce, “Does this mean we can one day have another Hitler?” Turning to Sorensen on the plane taking them from Berlin to Dublin, Kennedy himself said, “We’ll never have another day like this one as long as we live.”

Actually, he did have another one, later that week in Ireland. Kennedy’s ancestral home pulled out all the stops to greet him: thousands of miniature American flags were issued, shops and houses on the route of the presidential motorcade were given a fresh lick of paint, and it was said that a thousand extra pints of beer were laid on at Mulligan’s pub in central Dublin each night to supply the press corps. Some disparity existed between what the president’s hosts and JFK himself expected of the visit. When Dublin’s ambassador to Washington, Thomas Kiernan, raised the subject of a possible official statement on Irish reunification, Kennedy “visibly winced… He looked as if a headache had struck him, and asked me if he was expected to say anything in public.” In the end, he never did. Kennedy was content to take his Irishness no further than a few generic avowals of goodwill, and somewhat hazy late-night allusions to historical differences with the British.

Kennedy caused a minor furor when he went on to remind the Irish National Assembly that it had once been thought “not to inspire the brightest ideas.” Amid some murmuring and shifting in seats, he swiftly added, “That was a long time ago, however.” The eighty-year-old Irish president and former freedom fighter Eamon de Valera later erased these remarks from the parliamentary record of the visit. At a state dinner that night, de Valera told the room, “If you are weak in your dealings with the British, they will pressure you… Only if you are reasonable will they reason with you, and being reasonable with the Brits means letting them know that you are willing to throw an occasional bomb into one of their lorries.” At that Kennedy smiled and responded by leading the guests in some old sea shanties.

From there it was on to what the British premier Harold Macmillan called a “slightly loopy” house party at Birch Grove, Macmillan’s family home in the Sussex countryside. The free world’s two principal leaders made a droll pair, almost as if intentionally contrasted for comedy: the sixty-nine-year-old Macmillan, superficially dotty and benign, wearing an egg-stained cardigan under his jacket; the forty-six-year-old Kennedy clad in an elegant Savile Row suit, in one observer’s opinion like “a sort of MGM version of an English gent.” Before dinner the two statesmen went out for a drink at the village pub. The local police provided two unarmed men on bicycles to patrol the route, while the twenty-six Secret Service agents traveling with the president “operated upon somewhat cruder lines,” Macmillan noted. Once at the bar Kennedy bravely ordered a martini, a drink he finished with gusto, but which he later privately conceded had “tasted like brake fluid.”

Kennedy’s trip wasn’t all sightseeing and light comedy, however. He and Macmillan took the opportunity to hammer out a joint US-UK negotiating position for impending nuclear test-ban talks with the Russians in Moscow. These came to fruition the following month with an agreement that prohibited such tests underwater, in the atmosphere, and in space (but not underground), and allowed up to seven annual on-site inspections by each side. The treaty, ratified in the US Senate by a vote of eighty to nineteen, was widely hailed as a significant thaw in East-West relations, if not as the beginning of the end of the Cold War. Macmillan, who burst into tears of relief when he heard the news from Moscow, was later left to reflect on the indelible image of parting from Kennedy as the latter stepped into a waiting Marine helicopter on the lawn of Birch Grove. The premier saw his guest’s ascent into a cloudless English summer sky in almost spiritual terms.

“My friend was gone,” he wrote. “Alas, I was never to see him again. Before the leaves had turned and fallen, he was snatched by an assassin’s bullet from the service of his own country and the whole world.”