Vice President J.D. Vance’s family vacation in Britain was disrupted by protesters who insisted that he was not welcome in the country. In the Cotswolds, an area northwest of Oxford and the British equivalent of Martha’s Vineyard, ultraliberal white protesters huddled together on August 12 to make their meager numbers look large for the cameras, wielding signs bearing such slogans as “End Genocide!” and “Stop Fascists!” One participant quoted by the Guardian explained: “I’m most worried about his environmental policies. They risk eliminating the whole of humanity, all the creatures on the Earth.”

Coming the same week that President Donald Trump asserted greater control over Washington, DC, by taking over the city’s law enforcement, the Vance visit highlighted the tensions between local democratic rule and its frequent deviation from the public good. In both instances, the American leaders are saving localities from too much self-rule run amok.

Of course, the British government – despite being a Labour ministry – encouraged the Vance visit, including his sojourn in the Cotswolds. As with the “Nixon to China” playbook, it is Labour politicians who have traditionally played the role of transatlantic mediators because they are trusted to protect the national interest, as opposed to the often-slavish Tories. Nor did the gentle farmers of the Cotswolds as a whole necessarily disagree with the visit. The village where Vance stayed belongs to a legislative district held by Labour, but the region’s two other districts are held by a Conservative and a Liberal Democrat. It is fair to say that the median voter in the Cotswolds probably took the visit to be an acceptable exercise of diplomatic bridge-building by the central government.

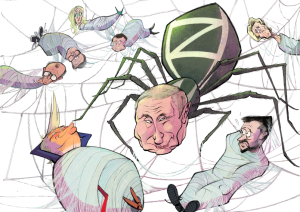

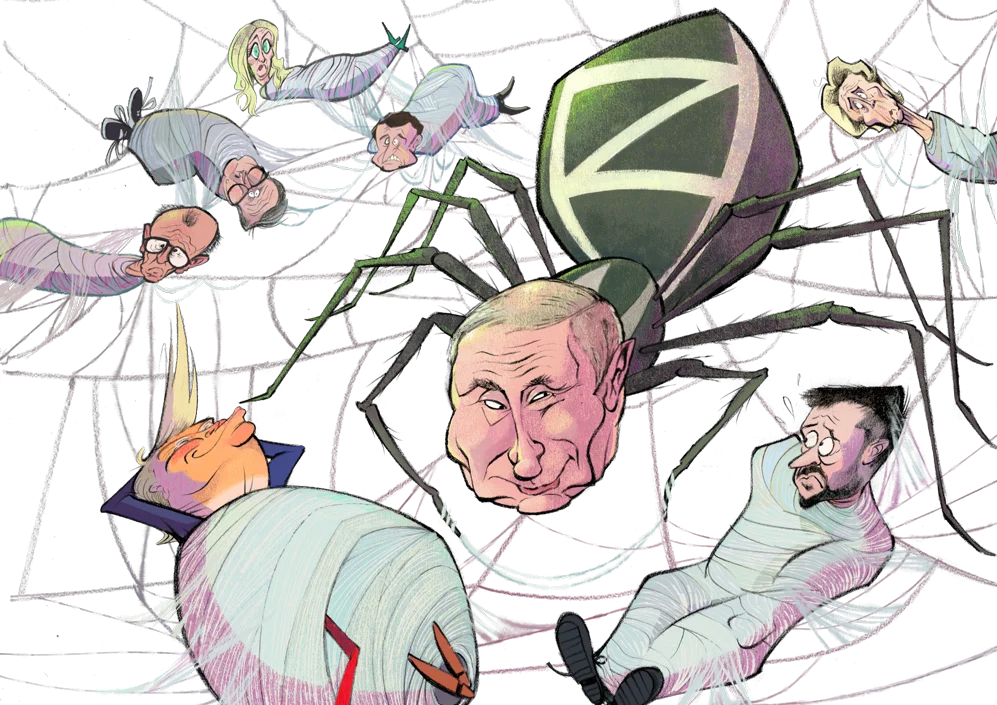

Rather, the real debate over Vance’s visit, and the reaction to it, was to do with who speaks for the Cotswolds in a longer-term, intergenerational sense. Like Trump’s check on DC’s home rule, Vance’s return to the ancestral mother country less as a visitor than as an envoy of Anglo civilization is a check on the home rule of a wobbling British nation. That, more than anything else, is why the leftist luminaries of British cultural destruction took to the grassy commons with their signboards and saucepans.

The Cotswolds region contains much of what is important in British history. I have walked over its excavated Roman settlements and through the remains of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, which resisted Viking control. The region also played a central role in the development of the English ecclesiastical and constitutional traditions, which were the basis of American colonial success. It played host to the first battle of the civil war between Charles I and Parliament (Powick Bridge, in 1642), as well as the last (Stow-on-the-Wold, in 1646).

In microcosm, the Cotswolds is the British civilization that the Americans have been called upon to rescue time and again. The American rebellion against George III was heralded by many English Whigs as a welcome tonic for their decaying democracy, where the voting franchise had shrunk to a mere 15 percent of adult males. The “special relationship” between the two countries based on their common culture and history emerged in the Victorian era when the US offered critical support to the liberal imperialism of the British empire. Britain, for its part, chose not to interfere with America’s Civil War. Winston Churchill’s famous Dunkirk speech of 1940 – looking forward to the moment when “the New World with all its power and might, sets forth to the liberation and rescue of the Old” – was merely reprising an old theme.

Vance’s rescue mission began with some fishing alongside the British foreign secretary and then moved through several pubs before decamping to Scotland. When a country, like a city, has lost its way, its external guarantor may be called upon to impose home rule. Like the long-suffering residents of DC, the British people will welcome their liberation and rescue.

Leave a Reply