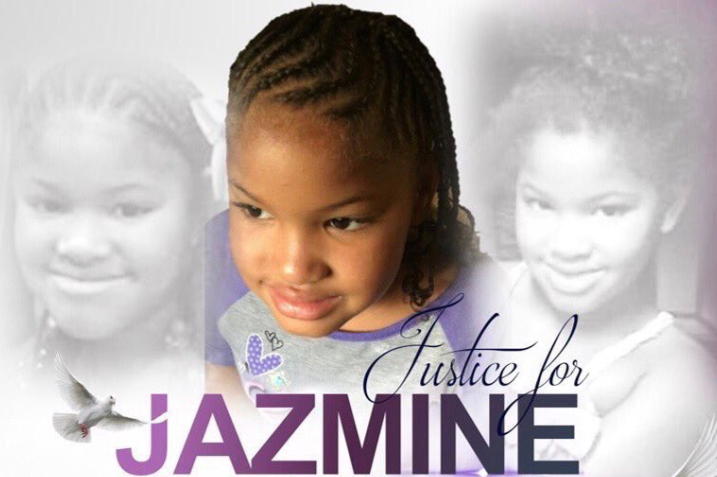

On December 30, seven-year-old Jazmine Barnes was killed in a brazen drive-by shooting in Houston while in her family car, driven by her mother. Barnes’s teenage sister provided the sole description of the shooter to media and police: ‘He was white and had blue eyes.’ In interviews, the family expressed fears that they had been targeted because of their race. The response was immediate: national media, celebrities, politicians, and activists launched a crusade to find the racist white killer.

Within days, activist Shaun King and his attorney Lee Merritt used social media to raise $100,000 as reward money for information leading to an arrest. Houston Texans star wide receiver DeAndre Hopkins committed one of his paychecks to the Barnes family. Shaquille O’Neal pledged to pay for the funeral. A GoFundMe page raised over $82,000 — far surpassing its initial goal of $6,500. On Twitter, celebrities and racial justice activists tweeted about the murder using the hashtag #JusticeforJazmine and #SayHerName.

The public outcry had an impact. Over the weekend, Harris County police announced a major breakthrough in the case: two men had been arrested — one charged — on suspicion of murder. Yet neither have blue eyes, nor white skin. Both are black. Whereas the family believed they were victims of a hate crime, suspect Eric Black Jr. admitted before investigators that mistaken identity was to blame. What’s more, in the wake of this surprising turn of events, those who made the loudest cries for justice became conspicuously quiet. Others maintained their outrage by resorting to a conspiratorial tone, sometimes questioning the police’s sequence of events.

It’s clear why the narrative around Jazmine’s murder should attract so much furor. The life of a black child being taken by a racist in a post-Charleston, post-Pittsburgh America should anger us. Yet it’s less clear why this furor should suddenly desist upon the revelation that the suspected killer is not white, but black. Black lives do matter — but the backlog of ignored tragedies in Houston similar to Jazmine’s case suggests that attention given to black lives by some within the activist movement is more selective than it seems.

In February 2017, eight-year-old De’Maree Adkins was killed by bullets that struck her while she slept in the backseat of her mother’s car. In June 2017, Messiah Marshall, a 10-month-old baby, died in his father’s arms after being shot outside his family’s apartment complex. The next month, 14-year-old O’Cyrus Breaux was shot and killed at his own birthday party. Within days, he was joined by 14-year-old Jaquan Neal. Then in January 2018, 16-year-old Stephen Verdell Jr. was shot and killed after leaving the Victory Prep Academy. In March, eight-year-old Tristian Hutchins became the victim of a drive by shooting while sitting in a car with his sister. She survived with a bullet injury in the leg, but Tristian died after a month-long battle at Memorial Hermann Hospital.

Though all similar to Jasmine’s case and in proximity to one another, these murders garnered a different response — if there was a response at all. National media didn’t provide blanket coverage. They were never mentioned by Mr King. Their names didn’t trend on Twitter. Activists didn’t crowdsource investigations. And their families didn’t receive any donations from celebrities. Why don’t these black children matter to ‘racial justice’ activists? Because without exception, their killers are also known or believed to be black.

Racial violence is a fact American society contends with, and over recent decades the media has made strides in responsibly reporting on cases involving historically marginalized groups. Yet, in today’s share-first-read-later world of social media, this interest toward racial issues has produced a perverse incentive. It is race, not our common humanity, that now plays a central role in galvanizing outrage over tragedies. Thus with black suspects in custody and the ‘white-on-black crime’ aspect gone, there’s nothing left to care about — leaving public interest to quickly evaporate.

It is bad enough that those with influence only stood by Jazmine as long as the racial narrative seemed true. It is worse still that this failure is perpetuated repeatedly throughout an informational ecosystem that exploits our issue-centric concerns and short attention spans. The easiness — and profitability — of manipulating our fears over racist violence has serious consequences for social tensions, particularly in a nation so bitterly divided as America in 2019.

This has been manifestly true for Jazmine’s case, where discussions of the murder frequently carried a tone of racially charged aggravation. A Salon column by University of Baltimore Professor D. Watkins called for ‘white America’ to accept responsibility for the ‘terrorist murder’ that took Jazmine’s life. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (D., Texas) urged the public to treat the killing as a ‘hate crime’ before any motive was established. Meanwhile, relatives of a white man misidentified by Mr King as a possible suspect were left in fear for their lives after being threatened on Facebook: ‘Someone is going to rape, torture, and murder the women and children in your family.’ Although racialized reporting may be good for clicks, it has dangerous consequences for those caught by the backlash.

There is a balance to be struck between standing forthrightly by victims of racism, and proceeding cautiously when coverage can have serious social implications. It’s not just the facts that are at stake, but our social fabric too.

Andy Ngo is an editor at Quillette. Wael Taji is a graduate student at Peking University.