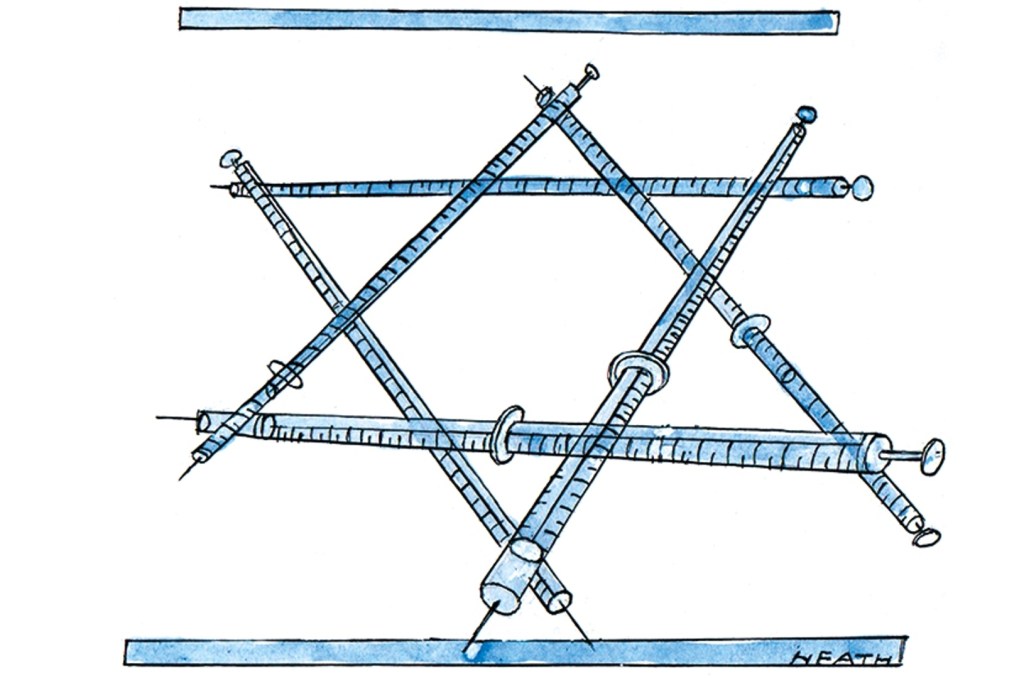

It’s time to think about your third COVID vaccine dose. That might sound like a premature suggestion when many people are still waiting for their second dose, and millions have not even received one. But Israel has just become the first place in the world to start giving a third, booster dose of the vaccine, and we should watch carefully to see if we can do the same.

There is growing concern that those who received the vaccine earliest in Israel could be the ones who are currently getting infected with the delta variant. Might that indicate their immunity has dropped to a lower level, and that the vaccine’s efficacy wears off over time? Experts working with the Israeli health ministry suggest it is too early to draw such conclusions. The data shows that the vaccine is still largely protecting the most vulnerable against serious illness even at six months and beyond. Even with rapidly rising infection rates, the number of critical cases is only rising slowly.

Having been the fastest country to administer first and second doses of vaccines to a high percentage of its adult population, Israelis now worry their progress is being threatened by the spread of the delta variant. Because they acted quickly and early, the initial vaccine doses were given long enough ago that some people’s antibody levels may be reaching the lower end of acceptability. I spoke this week with a volunteer in an ongoing antibody study, who told me her antibody levels have dropped rapidly. She’s a healthy nurse in her early sixties who works with immunocompromised hospital patients.

Israel made a deal with Pfizer early on which ensured it had a plentiful and timely supply of the vaccine in return for real-time patient data, thanks to the country’s decision some years ago to digitize medical records. Israel’s healthcare system is served by four competing healthcare providers, which also allowed the country to rollout the vaccines very quickly. Additionally, former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu agreed to pay Pfizer a high price per vaccine to ensure Israelis received them in good time. The country was therefore able to start giving out vaccines on December 21, 2020, and to carry out the most rapid per capita vaccination campaign in the world. At the time, some Israelis worried they were being used as the world’s guinea pigs, but most welcomed the opportunity to be among the first to be protected against COVID.

At this stage, nobody knows for certain how to interpret what’s happening in Israel. It’s important to remember that the first people to be vaccinated there were healthcare workers, the elderly and people with comorbidities or who were immunosuppressed. Healthcare workers, who are mostly healthy and middle aged, are not currently getting sick and dying. Everyone else who was vaccinated at the beginning of the vaccine rollout was high-risk to start with. Serology testing showed that even after their second dose they did not have the same antibody response as younger, healthier people. So their pre-existing at-risk status might be the reason some are now getting ill, rather than their earlier vaccination slots alone.

The supply of vaccines cannot keep up with worldwide demand. That scarcity means only the truly at risk will get a third dose anytime soon. In Israel the decision of who gets boosters is being made by the healthcare providers. They are prioritizing patients with suppressed immune systems, for example those who have received donor organs. In Britain, the government is considering the possibility of a booster jab for the most vulnerable this September and then for healthcare workers. During a single appointment, the third COVID vaccine dose could be injected into one arm as the influenza jab is injected into the other, in an effort to maximize uptake of both vaccines.

Meanwhile, Israel is also looking into setting up its own manufacturing capability to make vaccines domestically. Prime minister Naftali Bennett has said that the country’s independent ability to produce vaccines ‘is likely to be dramatic, especially looking toward the future and future pandemics.’

As before, other countries will be watching what happens in Israel to see how best to react when their own populations reach six months and beyond their second vaccination dose.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.