On September 28, the UN again imposed wide-ranging economic sanctions on Iran. Earlier in the summer, European powers had notified the UN Security Council of their intention to trigger the snapback mechanism within the original nuclear deal, the JCPOA, citing Iranian non-compliance with the terms of the original deal – specifically, the eye-watering percentages to which Iran is enriching uranium. And without a new resolution being agreed upon, the same sanctions that crippled the Iranian economy from 2013 to 2015, effectively dragging Tehran to the table in the first place, will have a devastating effect on ordinary Iranians who will see the value of their currency plummet and the price of daily goods skyrocket. The Iranian Ministry for Finance is considering reintroducing ration cards, albeit on smartphones. Yet for those elements of the IRGC and regime-linked oligarchy which have benefited from a thriving black-market economy, it might just be business as usual. Likewise for China, which will continue to enjoy cheap Iranian energy products.

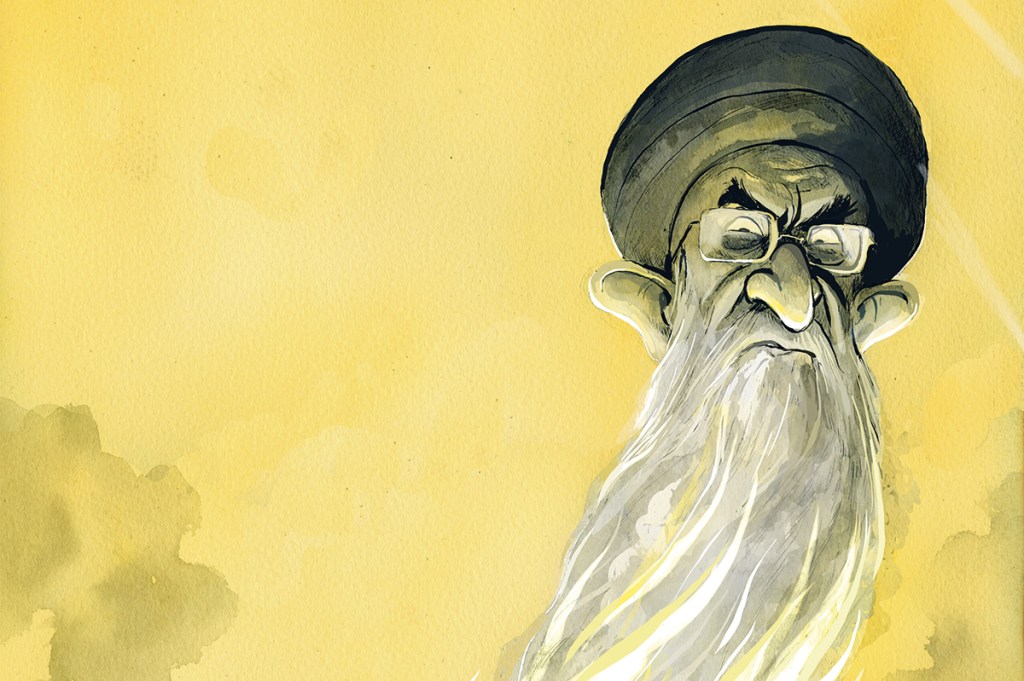

The Islamic Republic today is a markedly different entity from that of ten years ago

In many ways, we have come full circle from the pre-JCPOA days: Iran under sanctions, with no solution to the nuclear issue in sight. And yet, the Islamic Republic of today is a markedly different entity from that of ten years ago. Team Trump’s decision to blow up the nuclear facilities at Fordow and elsewhere may have been brilliantly executed by America’s Air Force. But it has not fundamentally altered the dynamics of the region.

Tehran is still a significant power – and has the energy potential to be an extremely rich one – but it is immeasurably weaker, having seen protests, war and economic collapse in the past decade. The old idea that Iran projected fear and influence through its dreaded proxies has been ruthlessly stripped away by repeated failures on the battlefield and within its intelligence agencies.

There is a whiff of the delusional in the rhetoric of the regime, which insists it won the 12-day war with Israel and continues to vow to destroy Tel Aviv, and so on. Esmaeil Khatib, Iran’s Minster for Intelligence, put on his best poker face as he proudly showed the world a documentary about how the Iranian intelligence services had successfully infiltrated Israel’s sensitive nuclear sites.

But before long, the joke was on him. It turned out that none of the photos or videos were from secret Israeli nuclear facilities, and nothing revealed in the video was more secret than the first page of a Google search. All very “Comical Ali,” though it’s no laughing matter for the many dozens of Iranians currently being executed for supposed links to Israeli intelligence.

The debate in Iran over the summer has broadly been split between two positions. One is to compromise on the nuclear issue and come to an agreement with the West that avoids another conflict with Israel. This, it is argued, would pave the way for Iran to return to the global economy as well as ushering in a measure of stability. Those we would label “moderates” or “reformists,” all of whom believe in the Islamic Republic, trumpet this position because they fear a revolution could follow the present situation.

The other position, adopted by Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, is to choose the path of resistance and trust that the Iranian people could absorb the consequences of sanctions and that the state could accept the increased risk of conflict with Israel and yet more diplomatic isolation.

Khamenei’s decision to reject a compromise on uranium enrichment and Iran’s ballistic missiles program was understandable if one sees it from his perspective; without a nuclear program and ballistic missiles, Iran would be more reduced in stature. Any compromise with the hated West, Khamenei knows, would be a fatal sign of weakness that could lead to turmoil for the regime. The Islamic Republic is built on resistance to foreign “tyranny,” obsessed with its independence and morbidly afraid of enemies within and without, real or imagined. Just look at what happened to Colonel Gaddafi when he caved in to western demands and abandoned his nuclear dreams, they argue in the Iranian parliament. Dead in a ditch.

Khamenei’s choice to pursue the path of rejection is not without risks. Put simply, Iran’s refusal to talk about its nuclear program, to decrease the percentages to which it enriches uranium and to pursue dialogue makes another war with Israel a matter of time, as certain Israeli politicians have said publicly and privately at that great diplomatic jamboree in New York that is the United Nations General Assembly. It sets these two adversaries on a collision course as Iran isolates itself from the world and Israel continues its rampage around the region’s sovereign nations.

The rhetoric in the Iranian parliament has been bombastic, with MPs in their dozens claiming that Iran must withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty, ban official weapons inspectors and review their nuclear doctrine that forbids the creation of bombs. Much of this rhetoric calls to mind similar threats at the height of the 12-day war over the summer, when those same parliamentarians voted to close the Strait of Hormuz. Alas, the vote wasn’t ratified by the Supreme National Security Council. Khamenei has sensibly distanced himself from talk of specifics, preferring to remain in the realm of vague threats and adherence to a tired revolutionary ideology of resistance to the West.

It’s fashionable to ask, “What should be done?” at times like this, particularly in the pages of serious publications. But perhaps a more sensible question is, “What can be done?” The lines of communication appear to be closed. Khamenei has repeatedly ruled out dialogue as the West is asking concessions of Tehran it is simply unwilling to consider. Once able to choose where and how it operates in the region and strong enough to absorb sanctions and their social consequences, it seems that Tehran’s choices are between “bad” and “a bit worse.” This all feels like an impasse, beyond which there are few positive outcomes.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply