Month after month, it just kept plummeting. The South Korean birth rate last year earned the not-so-holy prize for being the lowest in the world. The demographic crisis faced by South Korea seems hardly the hallmark of the country’s self-proclaimed status as a “global pivotal state.” That said, the country’s fertility rate rose incrementally to a high of 0.75 births per woman in 2024, marking the first time in nine years that any such uptick has been seen.

It is too early to say whether the tide is turning. Nevertheless, South Korea faces an unholy combination of an aging population (with the over sixty-five-year-olds accounting for 20 percent of the country’s nearly 52 million people) coupled with a catastrophically low birthrate. As is well-known, the demographic crisis is hardly the only one faced by the country, as the South Korean people wait to hear the fate of their impeached president, Yoon Suk-yeol.

A low birth rate will also have consequences for South Korea’s national security

South Korea, whose moniker of the “Miracle on the Han River” is testament to its rapid economic growth from rags to riches, is certainly no exception to the typical relationship between prosperity and fertility. As the cost of living rises — particularly with respect to housing and the cost of having a child, let alone more than one — skyrockets, the incentive to do so declines. Add to the situation a hyper-competitive job market, a significant gender pay gap, a lack of appetite amongst South Korean women to get married (let alone bear children), coupled with the inconsistent application of laws discriminating against pregnant female workers, and the reality of an almost non-existent birth rate is perhaps hardly surprising.

Having children in South Korea is not simply about the financial cost of childcare and schooling. In a society infatuated by educational achievement from a young age, private education in South Korea takes on a whole new dimension, as parents send children as young as five to hagwon — or private extracurricular educational institutions — even after a long school day. These classes, whether in English, mathematics, or otherwise, may not necessarily lead to stronger academic results on the part of the student. But on the part of the education provider, they are a lucrative means of gaining cash. Parents, too, may not enjoy having to send their children to these institutes, often during evenings and weekends, but as one South Korean mother once told me, “It is what everyone does.”

Though there may be a shortage of births, there has certainly been no shortage of incentives on the part of the South Korean government to encourage women to have more children. Indeed, one of the few areas uniting the ruling conservative People Power Party and the leftist Democratic Party is the recognition that something must be done.

In 2023, the government rewarded new parents with cash incentives, giving the equivalent of $530 a month to families which children up to the age of one, and $260 per month for those with children under two years old. These “baby bonuses” rose by 40 percent in 2024 when the government expanded financial support for working parents to enable them to take leave in order to care for children.

It will take time to ascertain whether the slight increase in South Korea’s fertility rate, coupled with a 1 percent increase in the number of marriages in 2023 — the first time any such increase took place in eleven years — is an aberration or a result of these policies. But the concern on the part of the South Korean government is clear, particularly as the percentage of the country’s aging population only looks to grow. If left unchecked, South Korea’s population is expected to shrink by nearly 30 percent by 2072 to a level last seen in the state’s pre-democracy era in the late 1970s.

A low birth rate will also have consequences for South Korea’s national security, in a country where military service is mandatory for all men aged between eighteen and thirty-five. Kim Jong-un has pledged to increase the size and readiness of the North Korean military. As the South Korean intelligence agency highlighted on Thursday, more soldiers have been deployed to Russia to assist Moscow’s war against Ukraine. In the South, a declining birth rate will inevitably mean fewer men able to be conscripted into the military, leading to concerns of how South Korea could hold its ground in the event of any possible inter-Korean conflict reminiscent to the Korean War. Whilst some politicians, such as Lee Jun-seok, the leader of the center-right New Reform Party, have called for mandatory military service for women as a solution to the low birth rate, such a proposal is hardly free from controversy.

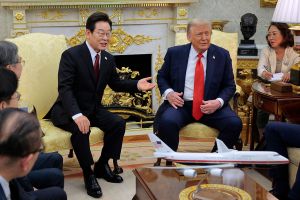

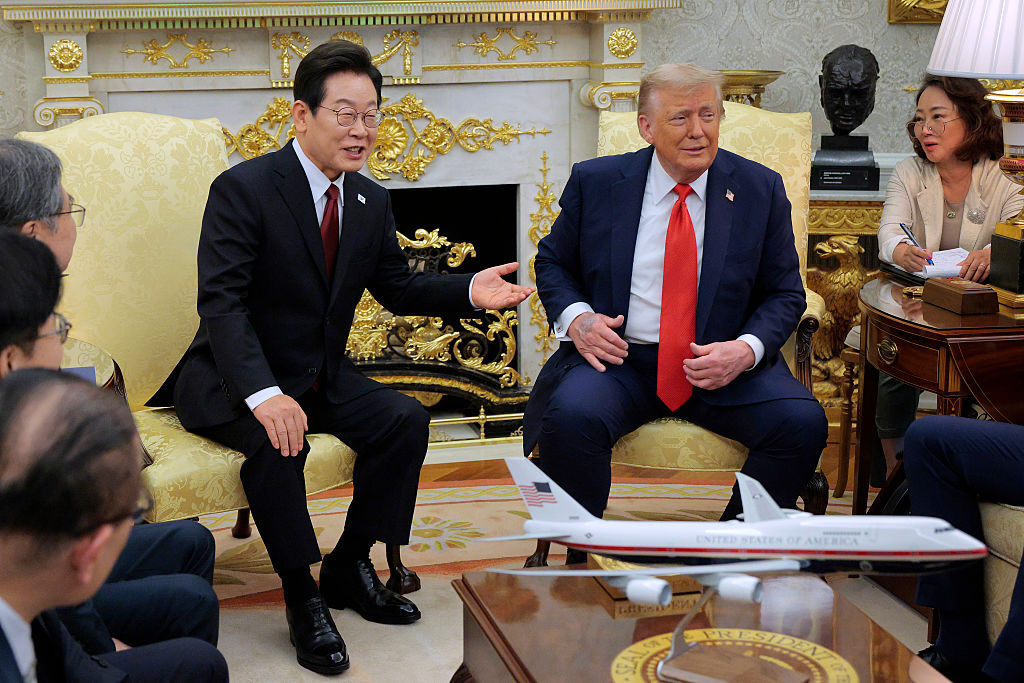

Yet before any further decisions on how to address South Korea’s population issues can be made, the country must first have a robust government to make such decisions. Earlier this week, in what would be his final statement at his impeachment trial, President Yoon offered the possibility of cutting short his presidential term, due to end in 2027, if the South Korean constitutional court does decide to reinstate his presidential powers. If enacted, the maneuver will likely attract much criticism. But as is the case in the United States, running a democracy is far from easy. Decisions, whether unashamedly allowing a strategic archipelago to fall into the hands of an enemy state or otherwise, must not be taken rashly.

Leave a Reply