In 2021, for the first time in 1,400-odd years, Britain ceased to have a Christian majority. The United Kingdom, the political entity of which the island of Great Britain has been a part since 1801, has had its share of not-quite-Christian prime ministers over the years, with a handful of agnostics and quiet atheists. But in 2022, for the first time, the UK had a prime minister who practiced a non-Christian religion – and Hinduism had the distinction of claiming the first post-Christian head of state, Rishi Sunak.

The West’s ethnic and religious foundations have already shifted in our great cities

It may be some time before an American president is Hindu. Already, however, there are several prominent Hindus in the Trump orbit and near the top of the Republican party. Vivek Ramaswamy hopes to be elected governor of Ohio next year, and his ambitions don’t stop at the state level. His 2024 run for president in the GOP primaries might have been less about winning the nomination than about raising his profile by serving, at times, as a proxy for Donald Trump. But he may yet get his turn at the top of the national ticket.

Ramaswamy is rumored to have a rivalry with J.D. Vance, the Ohio senator who became Vice-President. Vance is Trump’s political heir apparent; if he makes it to the White House, he’ll be the first Roman Catholic Republican president. His wife Usha, however, would be America’s first Hindu first lady. The Director of National Intelligence, Tulsi Gabbard, is the first Hindu ever to serve at the cabinet level. She had earlier, as a Democrat, been the first Hindu elected to Congress. There have been four others since then, all of them Democrats.

The year Gabbard first won a seat in Congress – 2012 – is also the year America ceased to have a Protestant majority, according to findings by the Pew Research Center. That was chiefly because of the rise of “nones” – Americans with no religious affiliation, most of whom come from Christian backgrounds. But Islam, Hinduism and other faiths are growing. Only about 1 percent of Americans are Hindu. Yet that makes Hindus as numerous as Episcopalians, who were once America’s establishment (if not actually established) Christian denomination: the church of George Washington, most signatories of the Declaration of Independence and roughly a quarter of all our presidents.

Least year, a delegation of Hindu Indian nationalists spoke at the National Conservatism Conference in Washington, DC. The international character of NatCon draws gibes from critics, but there’s nothing illogical about nationalists of different nations cooperating to promote the principle of nationalism itself, with liberal internationalism or globalism as a common enemy. Yet at dinner a Protestant friend told me he felt uneasy about the polytheist presence.

Two generations earlier, his grandfather might have had similar misgivings about getting involved in a coalition with Catholics or Jews. Since at least the 1980s, however, Republican leaders have made a point of professing their fealty to the exquisitely nondenominational thing that is “Judeo-Christian values.” Perhaps now it’ll have to be Semitico-Indo-European values?

The American right has always had a theoretical and theological problem here. Most on the right affirm that religion is most definitely the root of our nation and civilization. But it’s never convenient to specify exactly what that religion is: Episcopalianism? Certainly not. Catholicism? Evangelicalism? An ecumenical blend of theologically contradictory denominations with Judaism thrown in as well? (Never mind that Judaism itself comes in many varieties.) And don’t forget the Mormons.

With politics demanding such flexibility of the religious right, it doesn’t seem likely Hinduism will be where lines get drawn. But this, of course, highlights the impossibility of claiming that a heterogeneous political coalition is restoring a single faith. Yet there is an overarching tradition here, albeit one that exists in tension with strong orthodox belief. America’s Founding Fathers were, for the most part, distinctly latitudinarian: George Washington may have attended Episcopalian services, but it’s not clear he believed in the Trinity. John Adams was an avowed Unitarian. Thomas Jefferson redacted the Gospels to eliminate any trace of the supernatural; he self-identified on one occasion as an Epicurean. Later leaders dear to the right could be just as elusive in their religious commitments: Abraham Lincoln, Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump are cases in point.

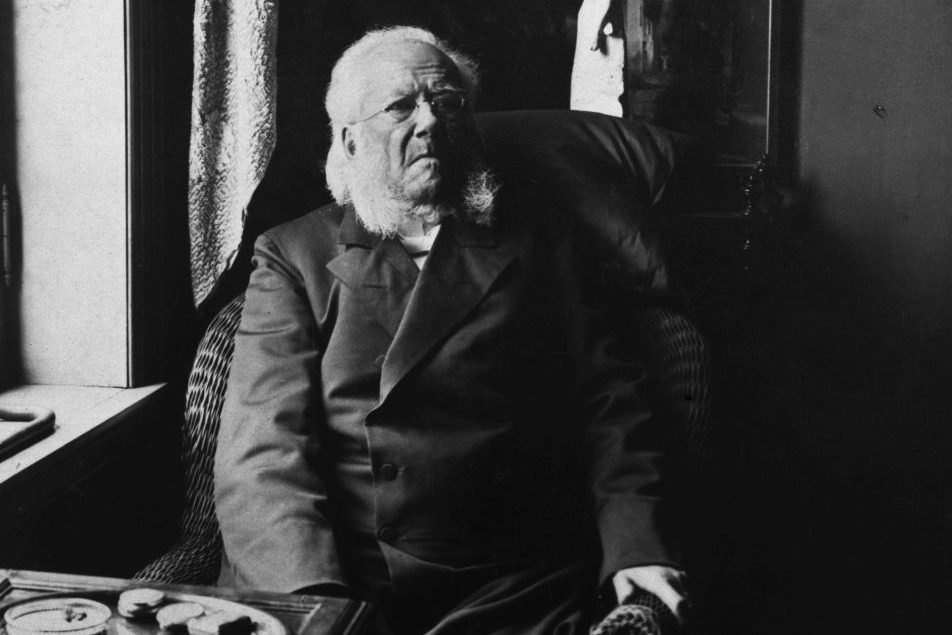

As for Hinduism, conservatism’s own founding philosopher-statesman, Edmund Burke, not only championed respect for the religion in India but offered a greenhouse on his Beaconsfield estate for the use of a visiting Brahmin envoy, Hunand Rao, who needed a place to perform Hindu rites. This was something of a scandal both to Enlightenment rationalists of the era and to Christians who thought Burke far too culturally accommodating. The traditions that Burke and America’s Founders sought to uphold were capacious.

The most devout men and women of today’s right want something more. Yet the demographics of the United States and Europe suggest the left and right alike will feel the need to enlist support beyond Judeo-Christian boundaries. If Zohran Mamdani succeeds in becoming New York’s mayor, two of the largest cities in the English-speaking world will have Muslim mayors from left-wing parties: the other being Sadiq Khan in London, where roughly a quarter of school-age children are Muslim. In European cities such as Vienna, the proportion is even higher.

The West’s ethnic and religious foundations have already shifted in our great cities, opening a gulf between them and the surrounding countries. The political geniuses of the 18th century built their systems on human nature, not just the conditions of the moment. Just how natural and adaptable those systems are is now being put to a test.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply