I turned to Xiaohongshu during the pandemic. At a time when I couldn’t visit China, the Chinese social media app (also known as “RedNote”) was a little slice of the motherland when I was bored with Instagram or Twitter. I was hooked immediately: like Instagram, the app is good for beautiful pictures and well-produced reels. It also has cute animals and an excellent sample of the dry wit of Chinese millennials. I’ve probably swiped through hours, maybe days, of short videos of beautiful street scenes from Chinese cities, vlogs from people who have swapped mega-cities for rural villages, cooking videos from all corners of the country, Mandarin comedy skits and dance routines in Han dynasty costumes.

But in the past few days I’ve barely recognized my Xiaohongshu timeline. English dominates and there are almost as many white faces on the app as Chinese. In a development I didn’t expect in 2025, a swarm of young American TikTokkers (#tiktokrefugees) have come to the app, fleeing TikTok’s imminent de facto ban in the US. Indigenous Xiaohongshu-ers have called it an “invasion.”

I have mixed feelings about this enforced multiculturalism. On one level, I have to admit there’s something beautiful, and beautifully subversive, in seeing Americans move to Xiaohongshu. Jumping into another addictive Chinese algorithm because you disagree with your government’s ban of a Chinese app is a commendable F-you to The Man. Regardless of your take on TikTok, is it really the government’s role to control what platforms their citizens can use?

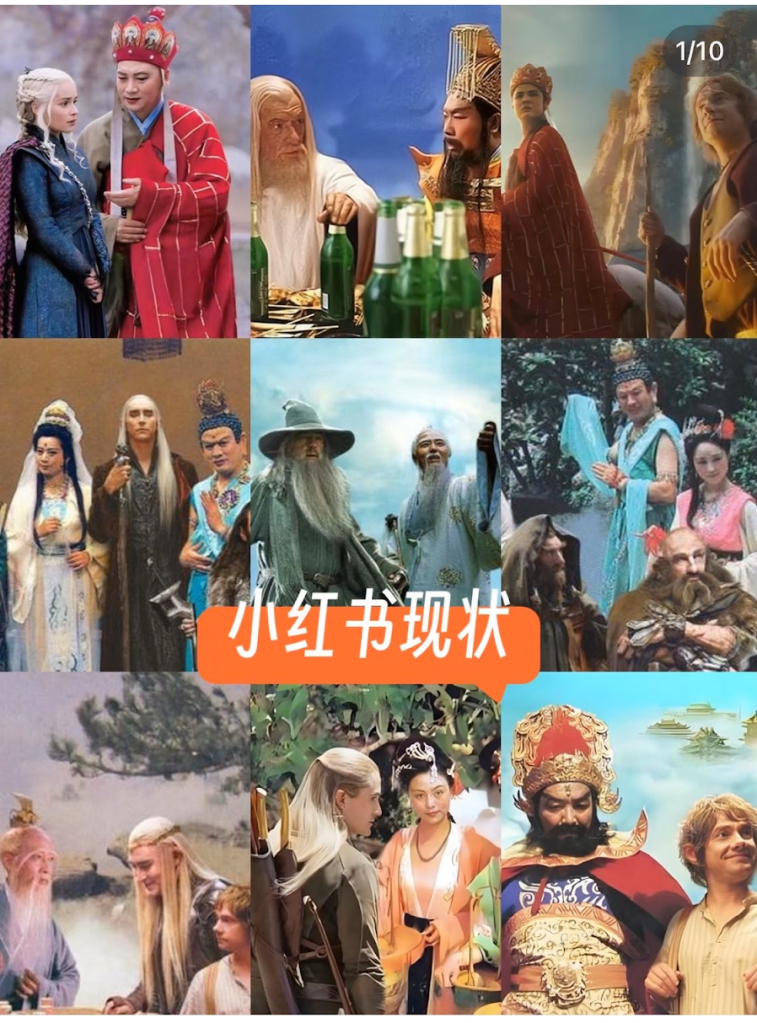

There’s also a fiesta feel to the Xiaohongshu community right now. For once, the Great Firewall has been broken down (at least in one direction). Americans, most of whom will never go to China in their lives, are seeing for the first time what ordinary Chinese people laugh about, talk about, how they live and what they wear. The result is an utterly unexpected exchange of Chinese and American culture, best captured by a photoshopped meme of Gandalf the Gray at a banquet with the Jade Emperor captioned “Xiaohongshu right now.”

Chinese users are dredging up what little English they remember from school (with some lamenting that they should have studied harder), while Americans are using translation apps to communicate in clunky Chinese. This has led to some light hearted teasing, such as Chinese users offering to swap a 100 renminbi bill for a $100 dollar as a memento (the exchange rate is about 7RMB to $1) or making some pretty cutting jokes at the expense of the Americans (“why do you eat like ur healthcare is free?”).

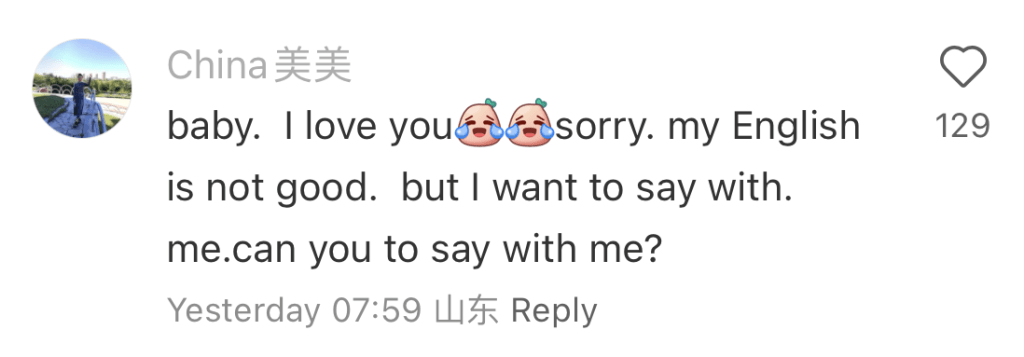

There have even been some more earnest (if slightly creepy) buds of cross-cultural romance: “baby. I love you. Sorry, my English is not good. But I want to say with.me.can you to say with me? [sic]” one commenter from Shandong declated to an American influencer who wears historical dresses. (A Chongqing user replies: “Even I don’t understand what you’re saying”).

An asymmetry underpins the interactions, as most Chinese will have grown up with Hollywood and may have traveled or studied in the West. They’re now collecting the most absurd questions they’ve been asked by Americans (“does China have cinemas?”) and busting some popular western myths about life in the country. The so-called social credit scheme, that supposed Black Mirror-esque digital surveillance scoring system, has been one of the first bogeymen to fall. (The misreporting of this scheme is something I’ve looked at in detail on my podcast, Chinese Whispers).

But for all the benefits of this multicultural carnival, I’m unashamed to admit my rather parochial irritation with the new and diverse Xiaohongshu. Scrolling through my timeline, it’s now hard to find actual Chinese content, and when I do, the comment sections are full of solidarity: “Thank god, I’ve finally found a vlog from a Chinese person,” says one. “I want to complain, I almost can’t find content from Chinese posters,” says another. Some Chinese posters even suggest mixing up the order of words to fool the translation apps. I imagine this is how I’d feel if my favorite restaurant in China was suddenly flooded with American tourists demanding knives and forks, English menus, cheeseburgers and extra large sodas.

The truth is this current anarchy probably won’t last. TikTok may well survive in the States; or the Americans may simply get bored. It’s even possible that Beijing will force Xiaohongshu to split into two platforms, for China and the West, just like how ByteDance has TikTok in America and Douyin in China. This aim of rebuilding the Great Firewall would not be to destroy the attention spans of Americans with a more addictive algorithm, but to “protect” people in China from being “corrupted” by the outside world. For now, Xiaohongshu has been continuing to enforce Chinese censorship rules, and even seems to have begun a hiring spree for in-house English language censors.

For my part, I simply hope that its unashamedly Chinese content doesn’t get diluted in this cultural melting pot. The Americans are welcome to RedNote, but can they please just lurk?