The vice-presidency of the United States has always been the butt of jokes. “I don’t plan to be buried until I’ve died,” quipped Daniel Webster when he declined William Henry Harrison’s offer of the role. John Nance Garner, who served as FDR’s vice-president, dismissed it as “not worth a bucket of warm piss.” Even John Adams, the first to hold the office, was equivocal: “I am vice-president. In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.”

He may prove to be a more effective standard bearer for Trumpism than Trump himself

That “everything” has proven elusive. Fewer than a third of vice-presidents have gone on to occupy the Oval Office and only four have won the presidential election while vice-president: Adams in 1797, Jefferson in 1801, Martin Van Buren in 1837 and George H.W. Bush in 1988. Yet few people would deny that J.D. Vance, the forty-year-old vice-president-elect who will be inaugurated on Monday, is now not only the overwhelming favorite for the GOP nomination in 2028 but that he also stands a good chance of winning the next presidential election.

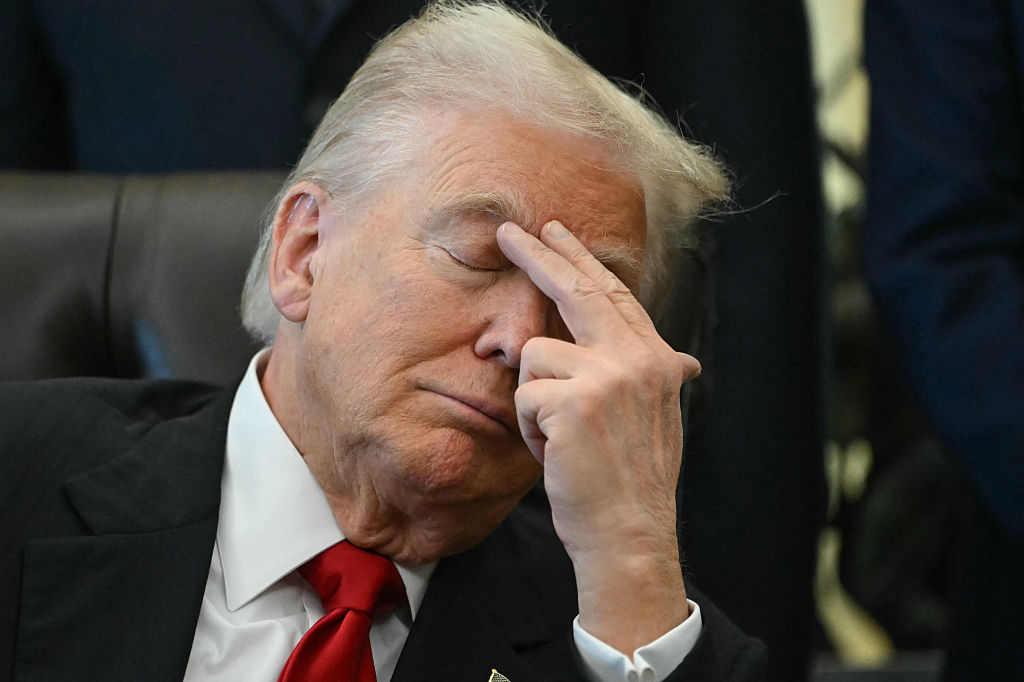

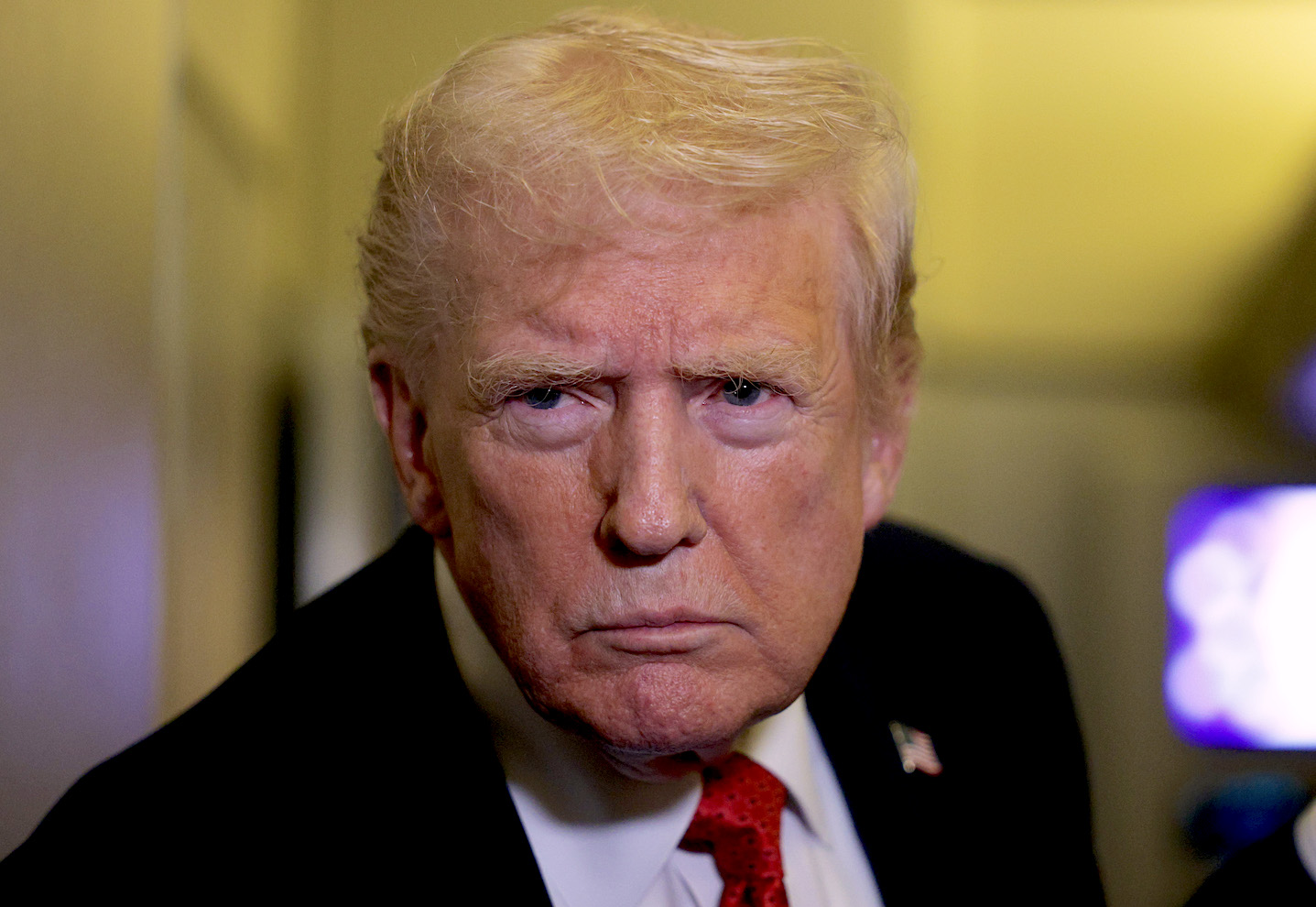

Donald Trump’s selection of Vance as his running-mate defied conventional wisdom. Running-mates are almost always chosen as a matter of pure tactical calculation, whether it is to add youth to the ticket (Nixon in 1952, Quayle in 1988) or experience (Biden in 2008, LBJ in 1960); to broaden a campaign’s geographic reach (Truman in 1944, Bush Sr. in 1980); or to appeal to women and ethnic minorities (Harris in 2020). It is a measure of how confident Trump was of victory that he dismissed these considerations. Choosing Vance was, by any measure, desperately risky: he entered the race as the least popular running-mate in modern history.

Why did Trump take the gamble? It was Donald Trump Jr. and Eric Trump who advanced the winning argument. If, the reasoning went, their father was to cement his transformation of the political landscape, the decision should be based not on who would help Trump win in 2024, but who would help Trumpism win in 2028. The Donald needed a dauphin. And no one was better suited to that role than Vance, Trumpism’s ablest and most intelligent communicator-in-chief since the publication of his bestselling Hillbilly Elegy in 2016, a remarkable evocation of the anguish and disillusion of Flyover America that to this day is the best explainer for the bewildered elite of Trump’s ascendancy.

My somewhat improbable friendship with Vance began years ago over long conversations mainly on theological matters, prompted by his conversion to Catholicism. I recall the relief of meeting someone else who had been forced to navigate his way through elite ecosystems without discarding convictions that made most colleagues reach for the smelling salts. I discovered that he too was convinced that Christianity was still the best engine for revitalizing an existentially exhausted western culture. We spoke little about politics at first; but our paths converged again when we found we were fellow travelers in National Conservatism, a movement that had gained momentum under the leadership of the philosopher Yoram Hazony. Hazony’s writings on nationhood and conservatism had made a deep impression on us both by drawing on a canon of neglected thinkers who pre-dated the rise of political liberalism. That pressed us to consider what had previously seemed beyond the pale: was there a world beyond liberalism and the extreme ideologies it had provoked? If so, what would it look like?

It is not a label he adopts himself, but Vance is indeed the first “post-liberal” to reach the White House. Insofar as that term denotes the group of wildly disparate thinkers busily writing liberalism’s obituary, it is uselessly imprecise. But Vance is a post-liberal in the narrower and more interesting sense articulated by Patrick Deneen, who claimed that liberalism failed not because a successor ideology usurped it, but because it has been so successful in its campaign to emancipate everyone from everything. On this view, left-liberalism’s demise is the predictable end-stage of an ideology that elevates self-determination above the obligations to family, community and nation without which no society can prosper. Right-liberalism, moreover, is cut from the same cloth: its genuflections to the unfettered movement of labor and capital, limited government and military adventurism are not only inadequate antidotes to America’s malaise but among the most aggressive catalysts of its decline.

Vance offers the prospect of a more muscular conservatism, one that is willing to wield executive power against a managerial elite that has defiantly subordinated the national interest to cosmopolitan concerns. I suspect that his ideological vision in the years ahead will not be a novel version of right-wing politics. Instead, it will involve the recovery of an older pre-liberal conception of statecraft, one directed unrepentantly to promoting civic virtue and social solidarity by political means.

Still, if you dislike the liberal right, wait till you meet the post-liberal right. Vance’s skepticism towards so many of liberalism’s axioms is bound to spook an elite class that has been wedded for decades to beliefs that have wrought irreparable damage on the kind of communities J.D. grew up in. If he holds his nerve, he may well prove to be a more politically effective standard bearer for Trumpism than Trump himself. The Donald, after all, has always been indistinguishable from the “limousine liberals” that thronged the business elites of Manhattan in the 1980s. His electoral success is based less on a reflective analysis of liberalism’s failures than on an intuition that the excesses of the progressive left have fueled national decline.

In any case, few now doubt that Vance has the caliber and vision to address the concerns of the New Right — deindustrialization, open borders, demographic decline, climate catastrophism, regulatory excess, institutional capture and woke ideology — and sustain the MAGA movement after Trump leaves the stage. Where Trump’s insurgency shattered the foundations of the postwar liberal consensus, Vance may soon emerge as the architect of a new political settlement, one that could reshape not only America but an increasingly fragile West.

James joined The Spectator’s Edition podcast alongside Freddy Gray to talk more about Trump, Vance and their approach to his upcoming presidency: