To the surprise of nobody and the disappointment of only a few, the Irish government has finally accepted reality and dropped its hugely controversial plans to introduce stringent hate speech legislation.

Under its original proposal, the Criminal Justice (Incitement to Violence or Hate and Hatred Offenses) Bill 2022 was so broad that it made Scotland’s much derided hate crime law look like a manifesto for free speech by comparison.

The proposed law, first introduced by justice minister Helen McEntee in November 2022, was always a divisive piece of legislation. It was condemned by many because it looked as if it been drafted by a committee of rabid social justice warriors rather than serious legislators.

Describing the 1988 Incitement to Hatred Act as “outmoded and no longer fit for purpose,” the new law would stretch the definition of “protected characteristics” to include (deep breath): “race, color, nationality, religion, ethnic origin, descent, sex characteristics, sexual orientation, disability and gender,” which included a person’s preferred gender and gender other than male or female.

In an effort to supposedly “protect” every single possible form of human life, the government and its advisors cast their net so wide that the whole venture became utterly meaningless. In fact, things reached such farcical levels that there was later clarification to point out the protection of “religion” also extended to “those of no religion.”

So in other words, atheists were now a protected characteristic who could complain to the authorities whenever a fundamentalist preacher said that anyone who hadn’t been saved by Jesus was doomed to eternal Hell fire. In fairness, plenty of Irish atheists were greatly amused by the fact that they were now a protected species and, had the law gone through, they had plans to launch as many frivolous complaints as possible — not to persecute the faithful but to point out the inherent flaws of this law.

Apart from being, by any rational measure, utterly absurd, it was also remarkably punitive, threatening massive fines and a five-year prison sentence for anyone found guilty of inciting hatred against someone with a protected characteristic, with incitement previously defined by the Irish government as “Intend[ing] to cause serious distress or alarm.” At the moment, the only evidence needed to prove a hate crime has been committed is the perception of the person making the complaint.

Having passed through the Dail before being blocked by the Seanad, the bill was then roundly criticized by rank-and-file members, who were encountering fury on the doorsteps from their constituents. With the issue of an election looming larger with every day, McEntee and her cabinet decided it was best to play the safe game and finally admit defeat. For now, at least.

On Irish TV this weekend, McEntee went full Kamala Harris when explaining her decision to park the legislation, saying: “Firstly, I think it’s important for people to know that we do have incitement to hatred legislation. While I don’t believe it’s strong enough, that’s why I had proposed to bring forward changes, because of the importance of this we need a consensus and what’s very clear, while there are quite entrenched views and you won’t always get a full consensus, you do need a consensus to bring it forward.”

Essentially, this translates into plain English as the minister for justice admitting that her pet project was a dog’s dinner and even her own party, let alone the wider electorate, had turned against it.

That’s not to say the proposal had no supporters. Both Labour and the Social Democrats have condemned the government for dropping the bill, with Labour leader Ivana Bacik solemnly describing it as “deeply regrettable” before claiming that the government was “apparently bowing to some sort of pressure.”

Who might be applying such pressure? What sinister cabal was nefariously pulling the government’s strings? Was it simply an electorate which has become sick and tired of a government which seems to have an insatiable urge to control every aspect of society; an urge which has only been emboldened since the Covid lockdowns?

Or might it, perhaps, have been the legal profession and civil libertarians who joined forces to say that the bill was both unreasonable and unworkable?

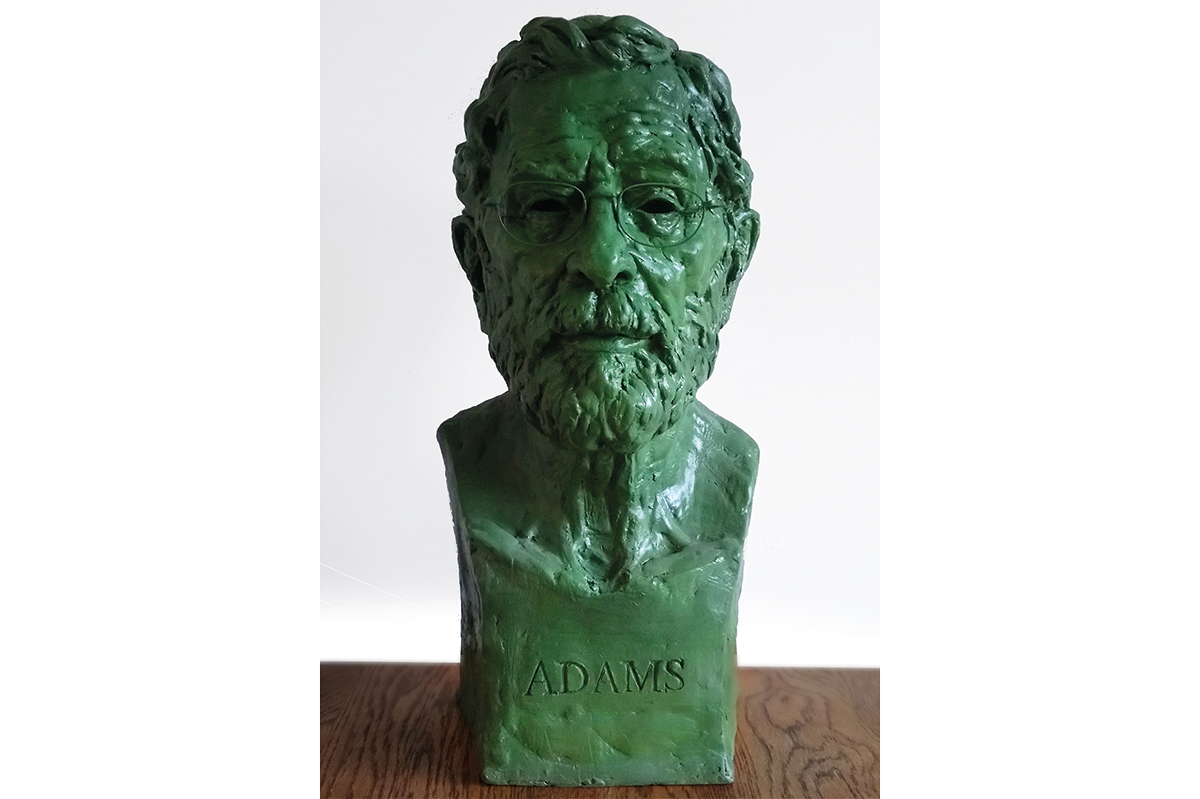

Might the government have been swayed by the fact that political players as staunchly opposed as conservative former attorney general and minister for justice, Michael McDowell, and far-left People Before Profit Paul Murphy were on the same page?

Would the fact that Sinn Fein and those who hate everything Sinn Féin stands for were, for this one moment, in agreement that the bill must be scrapped? Not a bit of it.

In fact, according to Labour’s Aodhán Ó Ríordáin, this was simply “gutless politics which has handed the far-right a win.”

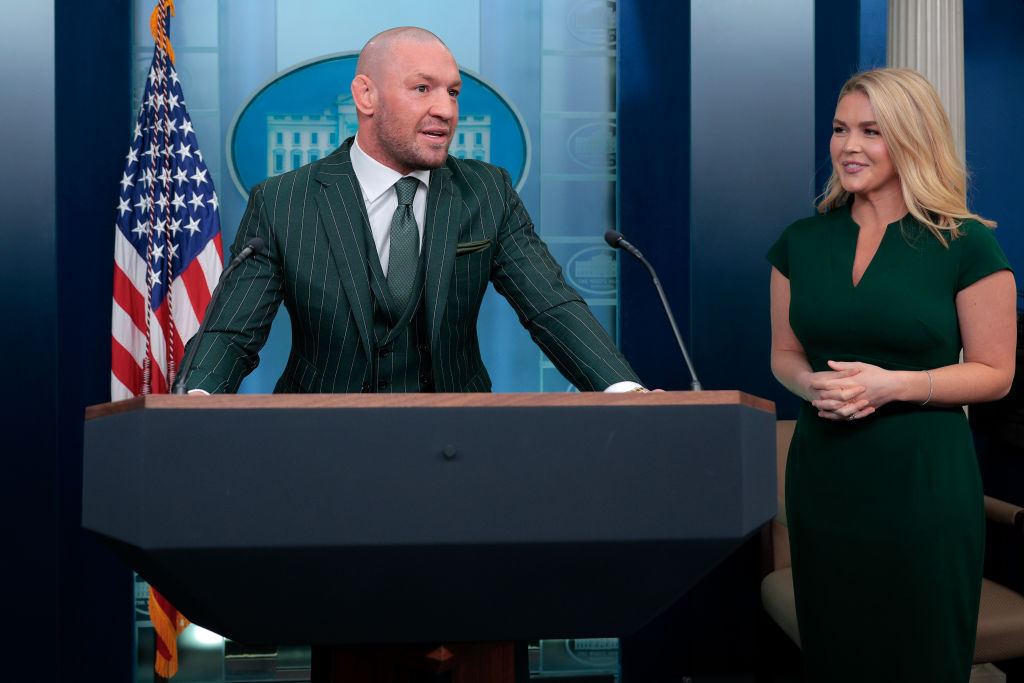

Given the fact that so called “far right” in Ireland is largely non-existent, electorally irrelevant and mostly consists of a few socially inadequate idiots who exist only to make everyone else laugh, it’s hard to imagine them holding much influence in the corridors of power. But in the febrile imaginations of those who supported the bill, it appears that conspiracies are everywhere when, as is usually the case, the truth is rather more mundane and nowhere near as exciting (although the fact that Elon Musk, Donald Trump Jr. and J.D. Vance have all criticized the bill allowed its supporters to convince themselves they were part of a global resistance movement against rich white men).

No, the real reasons why McEntee and Taoiseach Simon Harris decided that discretion was the better part of valor was because they realized it was never going to pass and their colleagues were complaining about defending a bill they didn’t support.

Factor that in, along with the catastrophic delays and massive overspend on the proposed National Children’s Hospital which has so far cost $2.4 billion and won’t be open for at least another two years, and being a government official suddenly became a rather sticky wicket.

With an election due in either November, or next February at the latest, hate speech was simply not a hill this cabinet was prepared to die on.

But the issue isn’t entirely dead just yet. According to a defiant McEntee, “I’m not scrapping it… I’m not walking away from it.”

In fact, in the admittedly unlikely event she should find herself returned as minister for justice in the next Dail, she plans to reintroduce it once more. What was the definition of insanity again?

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.