During a press conference in Tehran at the end of last month, Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps spokesman Brigadier General Ramezan Sharif claimed that “the al-Aqsa Storm was one of the retaliations of the Axis of Resistance against the Zionists for the martyrdom of Qasem Soleimani.” It was an extraordinary statement.

Iran had insisted that while it supported the al-Aqsa Storm (what Hamas calls its October 7 attack), it wasn’t directly involved in its planning or execution. Israeli intelligence believes this to be true. Despite receiving significant Iranian weapons and training, Hamas had not informed Tehran in advance of its plans. So why was Sharif suddenly claiming Hamas acted as part “of the Axis of Resistance” in retaliation for the American assassination in January 2020 of the commander of the IRGC’s expeditionary Quds Force?

Hamas leaders were incensed. In a rare rebuke to the Iranians, they issued a statement denying “the validity of the remarks made by the IRGC spokesman regarding the al-Aqsa Storm operation and its motives.”

The Iranians quickly retracted. The next day, IRGC’s commander-in-chief, Major General Hossein Salami, made it clear no non-Palestinian parties were involved in the attack. That wasn’t enough: Soleimani’s successor, Esmail Qaani, released his own statement, extolling the way “the Resistance groups have grown step by step… [they] make their own decisions and judgments.”

Seasoned Iran-watchers looked on with bemusement: the IRGC are not regularly made to squirm by their own proxies. It’s unimaginable this happening under Soleimani, the mastermind who built the network of Iranian influence across the region. But on the fourth anniversary of his death this week, without the magnificent act of vengeance the Iranians have promised ever since, perhaps his lifework should be viewed as an act of overreach. Which is why he met his end in a US drone strike at Baghdad airport.

Sharif ’s statement was a mistake. A momentary lapse of discipline caused by frustration within the IRGC over the recent assassination of Brigadier General Razi Mousavi in an Israeli airstrike on a Damascus suburb. For decades he was Soleimani’s right-hand man, working closely with Hezbollah in Lebanon, and was deeply involved in building up the Shia militias which propped up Assad’s regime in Syria.

After October 7, Iran’s star seemed to be in ascent. Hamas, which during the Syrian Civil War had been reluctant to be aligned with Iran, was back in the “Axis of Resistance.” Hezbollah, meanwhile, threatened to open a second front on Israel’s northern border, launching rockets daily and forcing 80,000 civilians to evacuate.

Hamas’s angry rebuke to the IRGC credit-taking disclosed a deeper frustration with Tehran

Further afield, the Houthi militia in Yemen were using its Iranian-supplied arsenal of missiles and drones to threaten shipping through the Bab el-Mandeb strait of the Red Sea. Shia militias in Syria were launching missiles and drones towards Israel. Iran’s aspiration to surround Israel within a hostile Shia crescent appeared to have finally been realized. But three months later, the Iranian axis is creaking. Hamas’s angry rebuke to the IRGC credit-taking disclosed a deeper frustration with Tehran. It expected Iran to order Hezbollah to launch a fully fledged war. Instead Hezbollah proceeded with a low-intensity campaign.

Hamas continues to boast about the al-Aqsa Storm. But it lost its only fiefdom, Gaza City, while its military wing, the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades, are being pounded. On Tuesday, an airstrike on a Hamas office in Beirut killed three of its members, including Salah al-Arouri, a senior leader believed to be involved in the planning of October 7.

Hamas is split. Part of the political leadership, based in Qatar, privately blames the movement’s chief in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, for gambling Gaza away. It wants Sinwar to negotiate a new hostage agreement, exchanging Israeli women and elderly men for a truce. Sinwar, however, is insisting on a much larger number of Palestinian prisoners to be released. Many of them are Gazans, while the prisoners released in previous truces were from the West Bank — another source of tension within Hamas. Divided and weakened, rival Hamas factions are looking for patrons, giving Iran’s rivals like Egypt an opportunity to weaken Tehran’s hold.

Hezbollah isn’t doing so well either: they have lost around 160 fighters in Israeli retaliatory strikes. They have been forced to retreat from the border and are coming under intense political criticism within Lebanon for risking a full-blown war. Tuesday’s assassination of al-Arouri also created a dilemma for Hezbollah. It took place in its main stronghold, the Dahiye neighborhood , but killed only Hamas members. It was a message to Hezbollah leader, Hasan Nasrallah, that he should keep out. On the Red Sea, the Houthis are running into trouble, as the US-led naval taskforce escalates its response to attacks on shipping vessels.

Iran’s mask is starting to slip. What was for years a shadow-boxing match with Israel is coming to the surface. On December 18, a cyber attack on an Iranian computer network paralyzed 70 percent of the country’s gas stations. A shadowy pro-Israeli hackers’ cooperative claimed responsibility. On December 23, a cargo ship in the Indian Ocean was attacked by a drone launched from Iran: the Chem Pluto was damaged but limped to Mumbai. Three days later, there was a small explosion near Israel’s embassy in New Delhi. No one was hurt; it had the hallmark of a hasty and botched attack.

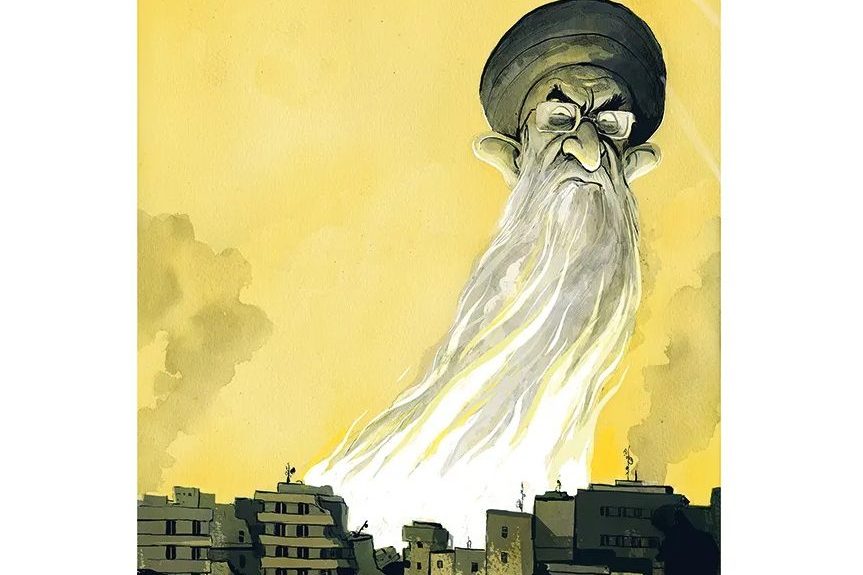

Western intelligence says Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is concerned that the proxies Iran built up over four decades are becoming too transparent. Iran sees them as a means of further exporting the Islamic Revolution and extending Shia hegemony. Iranians still live with the trauma of the deaths from the Iran-Iraq War — using proxies to fight its wars is a strategy to avoid repeating this.

But the events since October 7 threaten Iran’s policy of deniability. Israel and its western and Arab allies sense an opportunity to force Tehran to show its hand or retreat.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply