Four billion dollars in debt relief for black farmers only. Special stipends for Black, “Latinx” and Native American entrepreneurs. Minority- and women-owned restaurants prioritized for pandemic recovery funds. School admissions policies designed to reduce the number of whites and Asians.

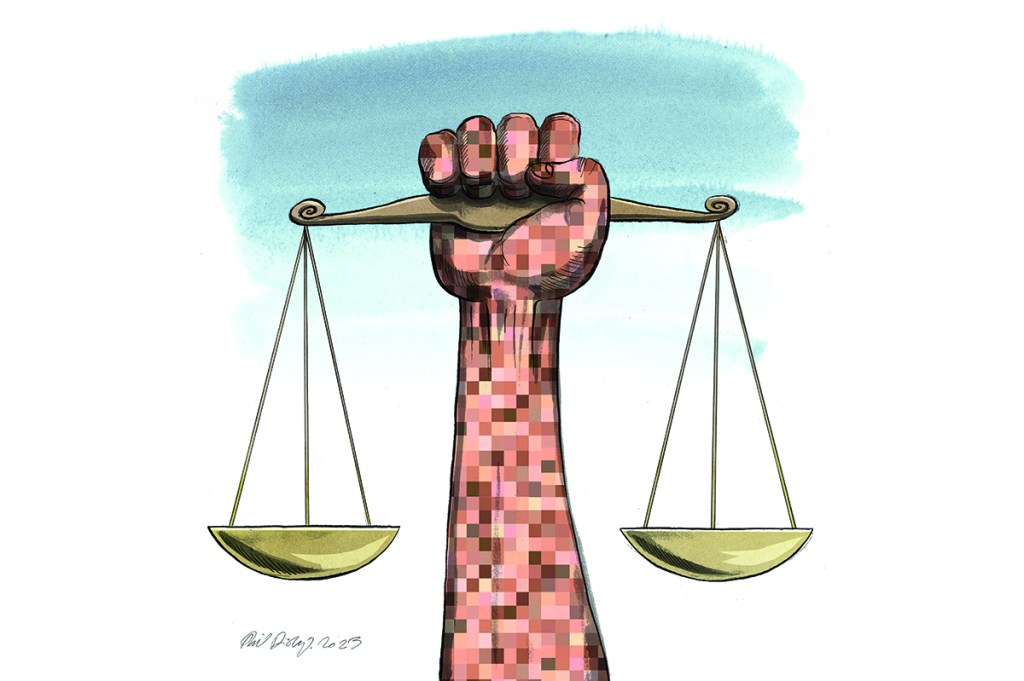

Racial preference programs have become ubiquitous in American society. When was the last time you filled out an official form without being asked to disclose your race? In the name of ending racism, we have been divided and labeled according to vague and outdated racial classifications that are then used to benefit certain groups at the expense of others.

Is there hope for a more race-neutral America? Optimists might point to the fact that the same conservative legal movement that took on, and defeated, Roe v. Wade is now taking aim at racial preferences in every facet of American life, from government programs to corporate hiring practices to school admissions.

A year after the landmark Dobbs ruling, conservative legal campaigners could secure another major victory. This summer, the Supreme Court will rule in Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and SFFA v. University of North Carolina, two cases that seek to eliminate affirmative action in college admissions.

The fight against affirmative action, and race-based programs more generally, isn’t new. Edward Blum, the president of Students for Fair Admissions and director of the Project on Fair Representation, has been assisting in the organization of anti-discrimination lawsuits for decades. In fact, he started as a plaintiff. Back in 1992, Blum ran for Congress in Texas and discovered while door-knocking that his district was aggressively gerrymandered to make it majority African American.

“I lost the election. But I sued the state of Texas, arguing that the district that I was running to represent was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. I had never sued anybody before,” Blum tells me. “We won. And it compelled the state of Texas to redraw virtually the entire congressional redistricting plan and reunite multiracial, multiethnic neighborhoods that had been split apart.”

Since then, Blum estimates he has been involved in well over thirty lawsuits, including Fisher v. University of Texas, the last challenge to college affirmative action programs that failed in 2016. He posits, though, that racial discrimination cases have become especially prominent since then.

“I think something has changed within the conservative legal community over the last five or six years,” he explains. “The second Obama term had such a focus on race-based rules, regulations and policies that it startled our friends in the conservative legal movement who really didn’t pay much attention to racial issues. And since the death of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement, most corners of the conservative legal movement are now very much aware of what is happening.”

The legal thinkers I spoke to for this article all agreed that they are now in a target-rich environment for litigation. Where progressives might once have tried to avoid obvious illegality by hiding the intent of their proposed programs, now, as Rick Esenberg, the founder and president of the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, puts it, they “say the quiet part out loud.”

“It was my perception, particularly following the summer of 2020, that there was a greater willingness on the part of governments and private corporations to explicitly treat people differently based upon their race or ethnicity, and that there was going to be a need to challenge that. And so we geared up,” Esenberg says.

WILL scored a major victory in 2021 when it sued the Biden administration over a program in the American Rescue Plan Act that provided debt relief only to farmers of color. The US Department of Agriculture claimed that the relief was targeted to “socially disadvantaged communities.” But one of WILL’s plaintiffs, farmer Adam Faust, who has two prosthetic legs due to being born with spina bifida, would not have been eligible for aid because he is white. A federal judge issued a preliminary injunction to halt the program, and the Biden Department of Justice opted not to appeal.

According to Esenberg, “both the government and private entities have been extraordinarily straightforward about doing something which is unconstitutional if it’s done by the government and, if it’s done by private corporations, generally violates some anti-discrimination law.”

Corporations have become another battleground for open-and-shut cases of racial discrimination. Woke boards of directors, environmental, social and governance ratings, and fear of hostile-environment lawsuits and bad PR have incentivized companies to carve out special advantages for employees of color.

Amazon, for example, recently launched a grant program that would give “Black, Latinx and Native American entrepreneurs” a $10,000 stipend to become delivery service partners to the e-commerce giant. America First Legal, founded by Stephen Miller, a former senior policy adviser and speechwriter to Donald Trump, is challenging the program in court. Gene Hamilton, AFL’s general counsel and a former Trump official who played a role in the end of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, is the lead attorney on the case.

After leaving the Trump administration, Miller and Hamilton started AFL to challenge antiracist discrimination in the courts. AFL’s Center for Legal Equality is specifically dedicated to taking on cases of racial discrimination that progressives push under the labels of “diversity” and “equity.”

“The ambition here is nothing less than the complete destruction of the equity agenda,” Miller tells me. “And it’s going to be defeated, ultimately, in our courts of law.”

AFL has been a trailblazer in this regard; CNN has described the organization as the “top legal foe of Biden initiatives,” citing victories against Covid-19 relief funds that were intended only for small businesses owned by women, veterans and minorities, as well as its successful case against the USDA’s discriminatory debt relief program for farmers of color.

Miller views his organization as taking the place of the American Civil Liberties Union, which has abandoned neutral application of civil rights law in favor of left-wing activism. He acknowledges the mountain of a task ahead.

“There’s just so many examples that the real question is not where is racial discrimination occurring, but where isn’t it occurring? In other words, what places are still safe from it? Americans have gotten so accustomed to this omnipresent, left-wing racial discrimination that it was sort of like the air that we breathe,” he says.

Gail Heriot, a law professor at the University of San Diego and chairman of the board of the American Civil Rights Project, surmises that the ACRP could knock out all racial preferences in a year if there were a thousand lawyers at its disposal. Instead, there’s one.

“It’s a manpower problem,” she says.

Heriot identifies several reasons why the conservative legal movement has only recently started to address civil rights violations on a major scale, particularly when it comes to private-sector discrimination. First, conservative lawyers are less likely to view the world in terms of race or sex. Second, lawyers who focus on these types of cases are more likely to be “canceled.” And finally, many organizations that make up the conservative legal movement were founded with a “libertarian impulse” that made them hesitant to go after private corporations.

Kenneth L. Marcus, the founder of the Brandeis Center and a civil rights attorney who served in the Bush and Trump administrations, also theorizes that because public-interest advocacy was pioneered by the left, it took conservatives some time to catch up.

“There are so many more challenges for conservatives legally now, as we’ve seen the rise of cancel culture, the expansion of woke-ism and more forcefully progressive racial preferences. On the other hand, the conservative legal movement has grown considerably to address these challenges,” Marcus says. “Now I think conservatives have a much better understanding of the extent to which law drives social change. There’s a much better understanding of the reality that the conservative movement needs a powerful legal arm if it is to fight back against some of the defeats at the Supreme Court.”

It might seem obvious that treating people differently because of their race is wrong, but the left argues that not only are laws and programs that benefit minority groups necessary to redress historical and current discrimination, increasing diversity is a compelling enough reason to disadvantage some groups. Esenberg disagrees. “You’re not really remedying any historic wrong because the people that you benefit are not the people who are wronged,” he says. “There were cases that were brought in the past by black farmers who had been discriminated against, and it’s perfectly fine for them to bring such a case and obtain a remedy for the wrong that was done to them. But to take another step and now say, we’re just going to treat black farmers as an archetype… that’s just to repeat the same sin that the civil rights movement fought against.”

David Bernstein, a professor at the George Mason University School of Law and the author of Classified: The Untold Story of Racial Classification in America, explains how the current racial classification system in America further undermines justifications for special treatment for certain racial groups.

“If you’re the son of the Nigerian ambassador to the United States and you come here for high school and decide to stay, and become an American citizen when you turn eighteen, you get the same preference for college as someone whose grandfather was a sharecropper in Alabama,” Bernstein noted.

There’s also a significant amount of scholarship on “mismatch theory,” which, when applied to affirmative action policies, suggests that members of minority groups may actually be harmed by the lowering of admissions standards.

“When the students don’t do well, instead of acknowledging that, of course, you would expect students with lower-end credentials to do less well, the response is, oh, it must be institutional racism,” Bernstein says.

The left’s reasons for enacting racially discriminatory policies become even more unconvincing when they end up harming individuals who might typically be considered part of a historically disadvantaged group. In an ongoing case in Virginia, parents are suing Fairfax County Public Schools for changing the admissions policy at a supposedly merit-based magnet school in a way that disproportionately works against Asian-American students.

Thomas Jefferson High School dropped its standardized admissions test and capped the number of students admitted from each of the district’s middle schools. Because most of TJ’s students previously came from three majority-Asian middle schools, the new admissions policy is projected to reduce the number of Asians at TJ by 43 percent. Erin Wilcox of the Pacific Legal Foundation is the lead attorney in the lawsuit, which was argued in front of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in September. The Fourth Circuit has yet to hand down its decision.

“You have to be able to show that not only is there a disparate impact on one racial group, but… that there was an intent for that to happen,” Wilcox says. “One of the things that’s so great about this case is that we have text messages; we have the school-board meeting transcripts where members were very clear on what they meant to do.”

One of the biggest challenges in any of these cases is finding plaintiffs. Challenging programs that claim to help people of color can lead to a full-frontal assault from activists and the media.

“The parents, these clients, they’re the heroes in this. I’m doing my job, but they are sticking their necks out,” Wilcox says.

Esenberg echoes her sentiment: “The folks on the left will do what they always do, and they’ll call them racists. And nobody likes to be called a racist. So you have to decide both as an organization, but also as a plaintiff — as just an ordinary person who’s been affected by this — that you’re willing to stand up for what’s right and you aren’t going to be deterred by these false and spurious allegations of racism.”

Miller argues that the conservative movement needs to mirror the left’s embrace of activists who stand up for their causes. Leading by example is great, he says, but the conservative movement also has to create an environment that is more radically supportive of the people who risk enormous social and professional damage by speaking out against the new discrimination.

“If you raise your hand and you step forward as a left-wing plaintiff, in many cases it will only enhance your career, enhance your financial well-being, enhance your standing, and you’ll be celebrated. And so we need to try to create an ecosystem that does the same thing,” says Miller.

The conservative legal movement’s recent victory in the Dobbs case only provides greater motivation to build up the infrastructure that could help it defeat the kind of codified racism that has become increasingly common.

“This is clearly a moment for the conservative legal movement to think big and act boldly,” says Marcus. “The current Supreme Court provides an opportunity to make real changes and not just incremental gains. There was a time when conservatives hoped that we might have narrow wins over technical issues, like narrow tailoring. But now that sort of a narrow win would almost feel like a loss. Now is the time to seek the sort of sweeping changes that would have seemed inconceivable only a few years ago.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.