In the summer of 1981, the American air traffic controllers’ union PATCO rejected a salary and benefits deal that had been put forth by the Reagan administration. What happened next lives on in the annals of Republican lore and in labor movement horror stories: PATCO opted for an illegal strike. More than 12,000 air traffic controllers walked off the job, and in one of the most successful union-busts in history, Reagan fired almost all of them.

That’s the official account anyway. But there’s much more about the strike that’s less known, or at least misunderstood. For example, did you know that PATCO had actually endorsed Reagan for president in 1980, finding Jimmy Carter too intransigent? The moment the walk-off was called, it became a high-stakes gamble between PATCO and Reagan. Air traffic controllers were forced to bet their jobs on the side they thought might win; most chose their union.

Yet perhaps the most ignored aspect of the strike is its economic backdrop. America at the time had been through years of grinding and seemingly unending inflation. Paul Volcker, Reagan’s Federal Reserve chair, set out to finally lick rising prices; by that summer, his Fed had raised interest rates to an eyewatering 20 percent. Workers were now suffering not just from inflation’s endless bites to their paychecks but the recession that Volcker’s policies had caused. For air traffic controllers, forced to work long hours under very stressful conditions, this was too much.

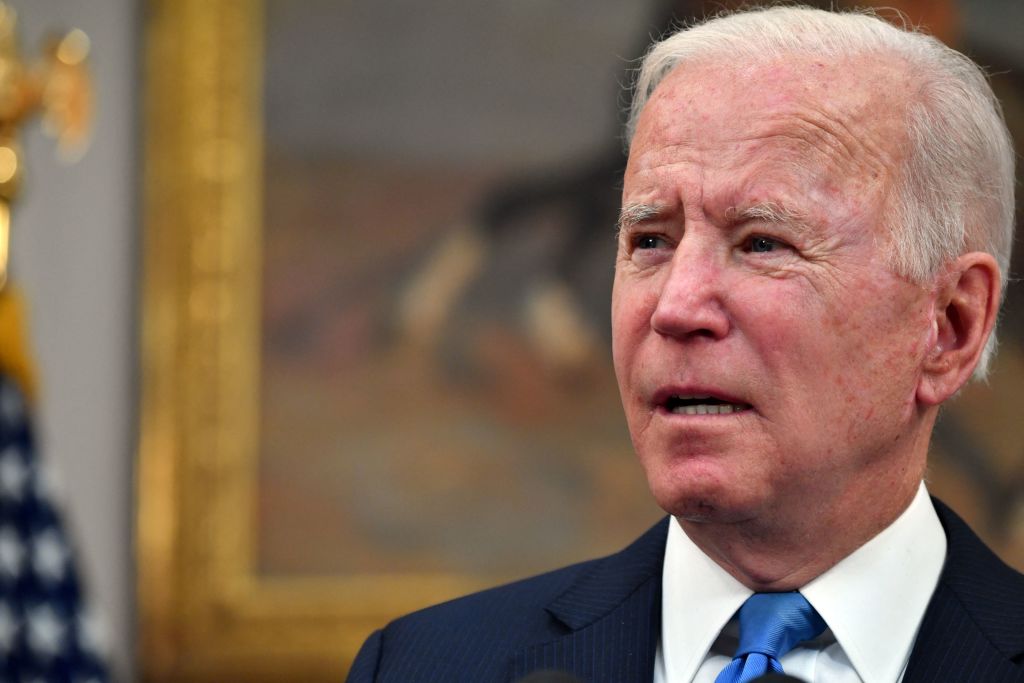

You may have noticed something here: this was not a “high-class problem,” as Joe Biden’s witless chief of staff Ron Klain called inflation last year. It was a hammer to the working class — and its blows brought about tension, social unrest and labor strikes. This is the real legacy of runaway inflation. And as Biden now falters and flails in his efforts to tame his inflationary beast, it may be in our future once again.

The Great Inflation of the 1970s actually began in 1965, though it grew more severe over time. It was the unplanned offspring of both runaway federal spending under the Johnson and Nixon administrations and the loose monetary policies of the Federal Reserve. Economists back then — even more than today, given the supply-side revolution that intervened in the Eighties — were overwhelmingly Keynesians. They believed it was government’s duty to spend whatever was necessary to bring about full employment.

It didn’t work. Not only did the costs of basic goods soar — in 1973 alone, the price of groceries jumped 20 percent — but by the mid-1970s, the unemployment rate had reached 9 percent, the highest since the Great Depression. Workers were hit hard and began to strike. In 1970, Congress voted to give postal workers a 5.4 percent raise. That sounds generous, until you consider that it was entirely negated by inflation. Hundreds of thousands of postal employees walked off the job and stayed gone for eight days. The country was stunned and the Post Office was forced to negotiate.

That same year, truckers touched off another wildcat strike. That stoppage was resolved with a pay increase, but as gas lines began to snake around the block because of the OPEC oil embargo, and inflation grew more severe, trucker stoppages became a feature of everyday life. Drivers organized into associations that acted independently of their unions. Key roadways and bridges were blockaded; food shortages were commonplace. Yet despite all this, the truckers were lionized, held up as gritty heroes by much of the public, who were as fed up with the bleeding economy as they were.

The 1970s were a time when, as David Frum has put it, “the United States sank into a miasma of self-doubt from which it has never fully emerged.” While there are many reasons for that crisis of confidence — Vietnam, rising crime, OPEC — one of them is surely runaway inflation. And it wasn’t just strikes and shortages. “Housewife revolts” erupted outside grocery stores as moms protested food costs. Two presidential administrations were engulfed, Gerald “Whip Inflation Now” Ford’s and Jimmy “Put on a Sweater” Carter’s.

In fairness, the 2020s are not the 1970s. Organized labor is weaker. The Federal Reserve has moved faster to raise interest rates, no doubt haunted by the failures of Nixon’s Fed chair Arthur Burns. Yet from across the Atlantic comes an echo and a warning. In late June, 40,000 British rail workers opted to go on strike, bringing its train network to a halt. Walkouts are now being threatened in industries across the United Kingdom, where inflation is only slightly worse than it is here.

However bad it gets in the UK, or in the United States, one thing should be clear: inflation is not a “high-class problem.” It is not a “transitory issue,” as some Democrats have said, or a “moral panic,” as a New York magazine article from last September put it. It’s a great destroyer — of the working class, of social cohesion, of presidents who fail to take it seriously. Joe Biden, take note: you’re no Ronald Reagan.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.