The narratives we tell ourselves about the past are hardly set in stone. It’s in this ambiguity where Tancredi Di Carcaci finds inspiration. Through his practice, the British artist contemplates, and sometimes perpetuates, the blurring of straightforward histories, especially that of art, as traditionally passed down. His sculptures – a mix of ceramic works and assemblages combining cast bronze, ceramic and hunks of marble and stone sourced from Siena, Egypt and elsewhere – have aesthetic and thematic roots spanning the Renaissance, neoclassical revival, Romantic painting and 20th-century modernism.

“For me, with art, I don’t try and restrict myself. Any passing thought that crosses my mind, I try and incorporate into the work and then try and make it in a homogenized whole,” says the artist. As much is demonstrated in Di Carcaci’s new body of work at New York’s Palo Gallery in his solo show, “Spoglia.”

The title nods to the conceptual starting point: that of spolia – Latin for “spoils” – referring to the practice of taking bits of pre-existing architecture from one place and installing them somewhere else. In this, they are stripped of their original significance and imbued with fresh meaning.

In the creation of certain works, Di Carcaci has effectively performed this existential disruption of culturally inscribed objects, making for case studies in their own right. Notably, there’s Death of Craftsman (2025), which consists of a rough-edged, horizontal slab of slate, backdropping a small bronze skeleton, whose arms transform into an elegant tangle of branches. In fashioning this memento mori, Di Carcaci recovered a piece of discarded slate that had been removed from Leicester Cathedral to make way for the new tomb of King Richard III (the 15-century monarch’s long-lost grave was discovered beneath a parking lot in 2012 and his remains were reinterred at the site).

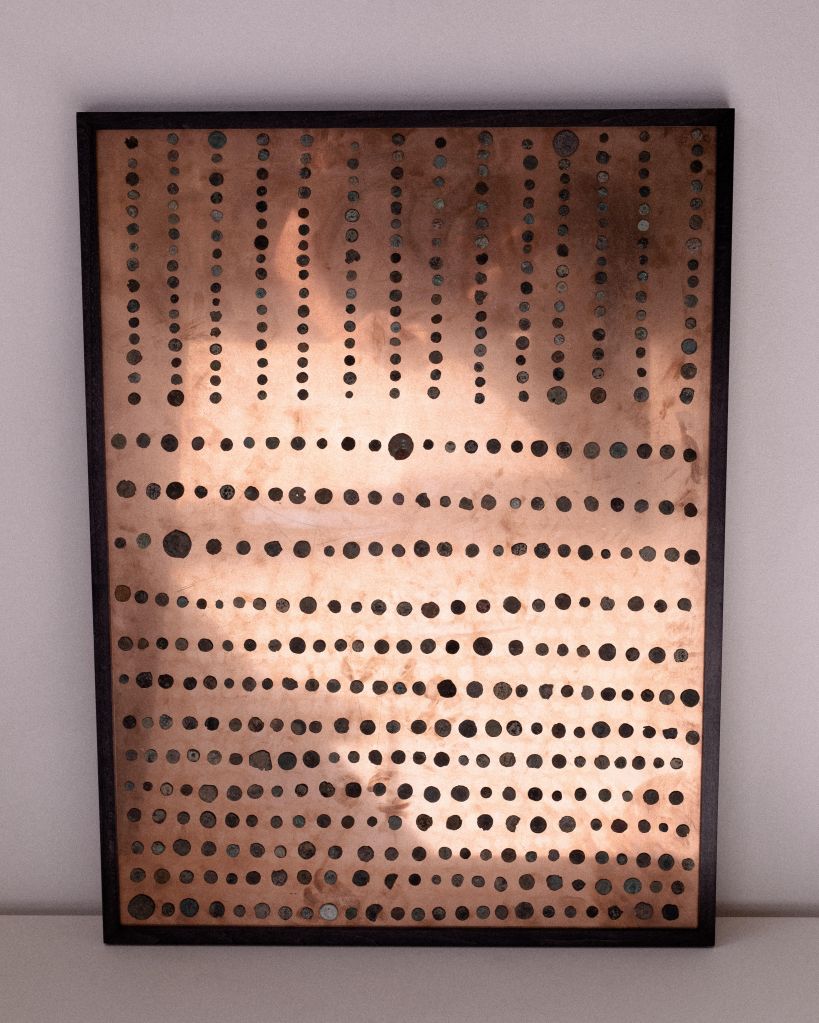

A parallel gesture is found in wall-hung bronze panels studded with ancient coins that range in date of origin from 100 BC to 400 AD and which the artist sourced from various auctions and dealers.

The otherwise prevailing trend across the body of work on view is the juxtaposition between figurative faces and abstract sculptural components. Take Future Icon (2025), wherein a raw block of green rice porphyry sourced from Egypt is topped with a polished bronze head. Several ceramic works, such as Shattered Icon (2025) were the result of Di Carcaci deliberately exploding vessels in the kiln and reconstructing the fragments into almost whirlwind-like shapes; faces then emerge from this chaos, like ghosts behind a veil. These faces are uniformly androgynous, nondescript and keep their eyes closed; with this, Di Carcaci intends for their impact to “be less abrupt. It lets you meditate,” he says.

The layman’s assumption when it comes to fine art tends to be along the thinking that valid artistic skill means creating effective realism, and therefore convincing realism in art is a sign that the art is good. This thinking in turn has lately led to a reactionary chorus of those who tear down instances of modern and contemporary abstraction, with frenzied accusations of elitism. Meanwhile, the poetry in the non-literal is dismissed.

In commingling realism and non-representation, Di Carcaci taps into this battle of cultural mindsets – which indeed seems to stand, however unnervingly, as emblematic of larger social trends. These sculptures, in the same breath, grapple with and interweave the competing realities of the present through a kaleidoscopic reclamation of the past. As tangible culminations of so many stories we’re told about where we came from, the works as much attest to the complications behind neat, linear histories as they threaten the fragile identities based on such assailable beliefs.

Leave a Reply