I’m owed around $680 billion. Some 77 acres of downtown Manhattan belong to the Carter family, according to a letter written in 1894. Wall Street, Broadway and One World Trade Center – they all sit on a plot that is, by rights, mine.

Yet here I am, grumbling about what ought to be in the pages of The Spectator. What went wrong? The story goes something like this. Shortly before independence, a pirate called Robert Edwards was licensed by the British to hunt down Spanish ships. He was so successful that the Crown gave him a slice of Manhattan as a reward. Edwards leased the land for 99 years to two brothers and subsequently died, lost at sea. That lease expired in 1877 and was supposed to be apportioned off to Edwards’s heirs. But that never happened.

“I simply want to know if the Foreign Office is aware that Mr. Harry Wyndham Carter is, by descent, one of the claimants to the alleged Edwards estate in New York,” wrote Lord Clifton to Sir Edward Grey, then a minister in the British government and later ambassador to America. In the document, which I found in the National Archives in London, Lord Clifton says the estate was then worth about £1 million a year. If Harry had received his 77 acres, his income would have been slightly higher than Cornelius Vanderbilt’s. What Clifton doesn’t say is how exactly my cousin, four times removed, had established that he was the rightful inheritor of the estate. The letter has an air of haste, great swishes of black ink underlining facts and names. The reason for the urgency was that poor cousin Harry was in prison.

As editor and proprietor of the Kennel Review, a magazine dedicated to dogs, he had managed to rack up some debts. His creditors planned to seize his rare books and some of his dogs from the family home in Kent. Outraged, Harry arrived just before midnight with a posse of around 20 men. They barricaded themselves in the house with “cases of champagne and other materials for conviviality,” according to one newspaper report. As well they might, given Harry was soon to be among the richest men in the world.

After some time, he appeared at the window with a revolver and asked the bailiffs to remove themselves from his garden. “Now I give you fair warning that if you do not get off my premises when I have told you three times to do so, I will shoot you.” “Three,” he counted down from the top of the house; “two,” the bailiffs watched on, maintaining the blockade; “one.” Cousin Harry managed to clip one of them, ever so lightly, somewhere around the eye, and the man promptly took himself off to the local hospital.

The police decided to get involved, also surrounding the home but not daring to interrupt the party. The next morning, Harry appeared again at the window and managed to negotiate an end to the siege. He emerged, “accompanied by two women, smoking a cigarette.” So began his sorry persecution at the hands of the British state.

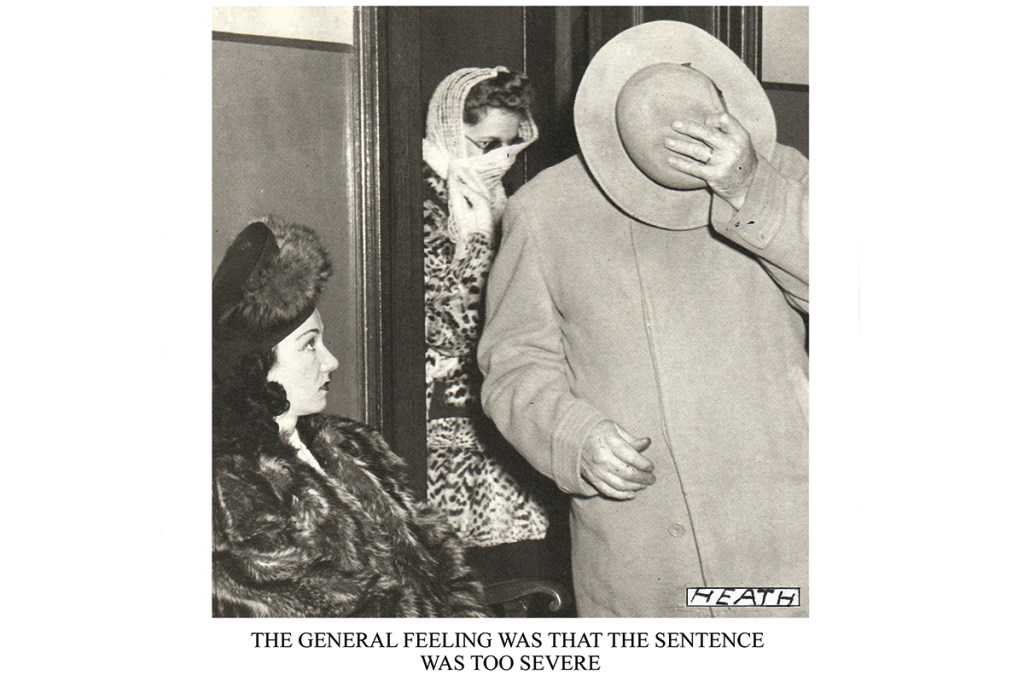

He was locked up for five years. Apparently, women swooned in the court as the sentence was read out. “It was the one topic of every club, inn parlor and bar,” explained another newspaper report, “the general feeling seemed to be that the sentence was too severe… especially among the fairer sex.” A petition to have his sentence commuted was organized. It was even signed by one of the jurors who had convicted Harry. Meanwhile, my cousin “made enquiries as to the allowance of cigars, wine and whiskey during his incarceration.” His imprisonment was less jolly than he’d hoped. Lord Clifton began campaigning for his release, bringing cases against prison officers for mistreatment. An exoneration and compensation committee was set up in his benefit, but it was no good. He was declared bankrupt while in prison. “Five years of penal servitude have made him wholly mad and he is now a pauper lunatic,” read the papers. On his release, he was sent to an insane asylum.

Yet somehow he managed to escape. He was convinced that a conspiracy had deprived him of his New York inheritance, a conspiracy that went to the very top of the British state. While on the run, he wrote a letter to Queen Victoria’s private secretary, expressing his frustration in colorful language. “I am fully swindled of liberty and money… The Queen’s life is not worth a penny until she treats me properly and meets my demands.” And then he added some slightly unfortunate bits about potentially shooting the Queen.

Royal residences across the country were put on high alert. Harry was hunted down – and found having lunch in a restaurant with a young woman. He was sent to Broadmoor Hospital for the criminally insane and, after serving 43 years, died in 1938. And with him went the proof that the Carters are the rightful inheritors of much of New York.

But Harry wasn’t the only person seeking the Edwards estate. Over the years, thousands have claimed they are the descendants of that British pirate, and thus rightful heirs to his 77 acres of Manhattan. There was the Pennsylvania Association of Edwards Heirs which in the 1990s crowdfunded $1.5 million for a suit to reclaim the land. The courts rejected their case and the association eventually collapsed amid accusations of embezzlement and fraud.

Historians today say the Edwards estate was a hoax. But of course they would. The great swindle of Harry Wyndham Carter continues to this day. His patient records will be declassified in 2038 and I’m confident that when they are, the world will know that I’m rightfully the heir of Manhattan – and I’ll shoot anyone who disagrees. You can join my posse if you like. I’ll bring the champagne and revolvers.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 15, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply