It was Argentina’s “liberation day,” Javier Milei proclaimed last week after meeting US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent in the Pink House, Argentina’s presidential palace. On Friday, he had shocked the country by lifting the cepo – “clamp” in Spanish – which has restricted currency trades in South America’s second-largest economy for so long. “After 15 years of capital controls, we have cast off the anvil to which we were chained,” Milei said.

Lifting the cepo was a key part of Milei’s policy agenda. Nevertheless, few expected him to do anything before mid-term elections in October. But doing so was a key requirement of the disbursement of $20 billion from the International Monetary Fund, also announced on Friday. While Milei has taken huge strides in improving Argentina’s fiscal position – running a budget surplus last year for the first time in decades – he still desperately needed cash to continue with his political project of reshaping Argentina’s politics.

First introduced in 2011 by then-president Cristina Kirchner, the cepo placed a range of restrictions on the trading of the peso. Argentines were restricted in the number of US dollars they could buy each month to just 200, while Argentine companies were largely blocked from sending profits overseas. This was seen as necessary to stabilize the economy, but was criticized for placing restrictions on businesses, limiting profits. Anathema to an “anarcho-capitalist” libertarian like Milei.

Among other things this has led to the bewildering array of different exchange rates. Check Google for how much your pounds are worth in Argentine pesos and you will see the official exchange rate – but no one pays that. Instead foreigners pay the “black market” rate, also known as the “blue dollar.” You get this by sending yourself cash via Western Union or exchanging cash on street corners. A large industry has been established around off-market currency exchange. One WhatsApp group dedicated to buying and selling cash has nearly 1,000 members.

Friday’s announcement caught Argentine financiers off-guard. Banks were reported to be racing over the weekend to update their systems to be ready for opening time on Monday and there was fevered anticipation as to where the dollar would open. Markets have reacted with delight to the news. The Argentina stock index was up by more than 5 percent, while the price of Argentine banks soared by double-figure amounts. Earlier this week, Milei mocked Martin Rapetti, the director of the think tank Equilibra, who had predicted a devaluation of the peso, calling him an “econo-swindler… who devotes himself to poisoning the population’s blood.”

A key part of Milei’s plan involves boosting foreign investment in the country. There are certainly investors sniffing around Argentina’s lithium and natural gas reserves – and Milei has offered large tax breaks to further entice them. But it is entirely possible that the positivity currently being trotted out by Milei and financial commentators is overblown.

Foreign investors know there is opportunity in Argentina. They also know that political instability and inflation has long been a fact of life. Milei is doing his best to institute neoliberal economics and achieve stability. But long-time Argentina observers know that there is every chance a Peronist victory in two years could see the country hurtle into another neck-breaking about turn. Milei remains popular, but he has virtually no support in Congress and relies on a coalition to support his agenda. The mid-terms could change this, but that will not alleviate Milei’s immediate problems.

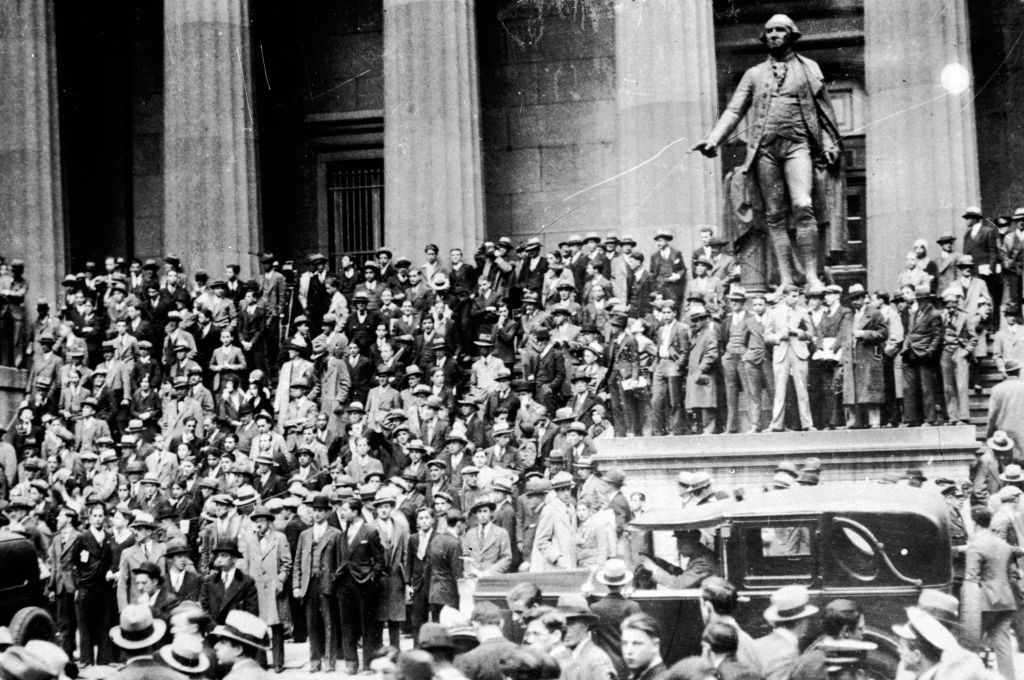

The IMF deal, meanwhile, is a vote of international confidence in Milei’s leadership and policies. It has allowed Milei to lift the cepo, but only by relying on debt. Argentina was already the largest debtor to the IMF by some distance before it borrowed a further $20 billion – and it has defaulted before. The IMF has drawn criticism globally, but certainly in Argentina for supposed meddling in domestic politics. It was a key supporter of the currency-pegging policies that in part led to the 2001 economic collapse – the worst in the country’s history. Milei himself has been highly critical of the organization in the past, telling the Financial Times in 2023 that the IMF are a “bunch of bureaucrats who know that a bank’s business is to charge interest.”

But what do regular Argentines think? In truth many will be largely unaffected. Partly as a consequence of the 2001 crisis, few trust banks with their savings, instead stuffing their mattresses full of US dollars. A viral clip on Instagram perhaps held the answer. Asked what he thought of the lifting of the cepo, a young man clutching a hot dog at 7 a.m., said: “I’m 28 years old. I swear, I don’t know what color [a dollar] is. Green I imagine.” Another says: “What cepo? I’ve just come from the nightclub.” The news isn’t quite cutting through.