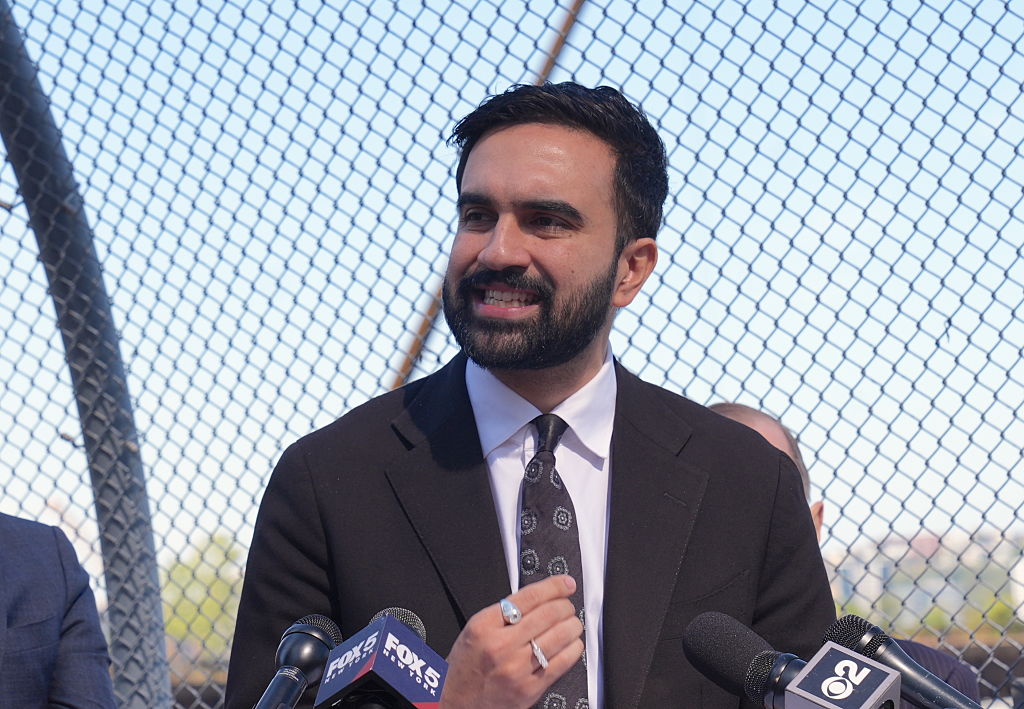

As fire-breathing counter-revolutionaries go, Christopher Rufo seems notably mild-mannered. Perhaps it’s his northern California roots and Pacific Northwest home that keep him from embracing the based lifestyle pursued by so many conservatives in the Trumpian era. He doesn’t like sports. He doesn’t enjoy UFC. He allows his four kids to watch Disney movies and admits he was once a vegetarian. Yet it’s also possible that the Georgetown-educated PBS documentarian turned right-wing iconoclast is effective precisely for that reason: he knows the people he is criticizing.

No individual activist has come to prominence in recent years as much as Rufo, who went from doing relatively low-level work within the sphere of conservative think tanks to being a fierce critic who leads the charge, across multiple media platforms, against the institutions and figureheads of the world of higher education. He is a recipient of the Bradley Prize, one of the most significant awards in the world of conservative non-profits, in recognition of his work. Rufo weaponizes his audience, informs them and updates them on his targets – and is often surprisingly open about his plans.

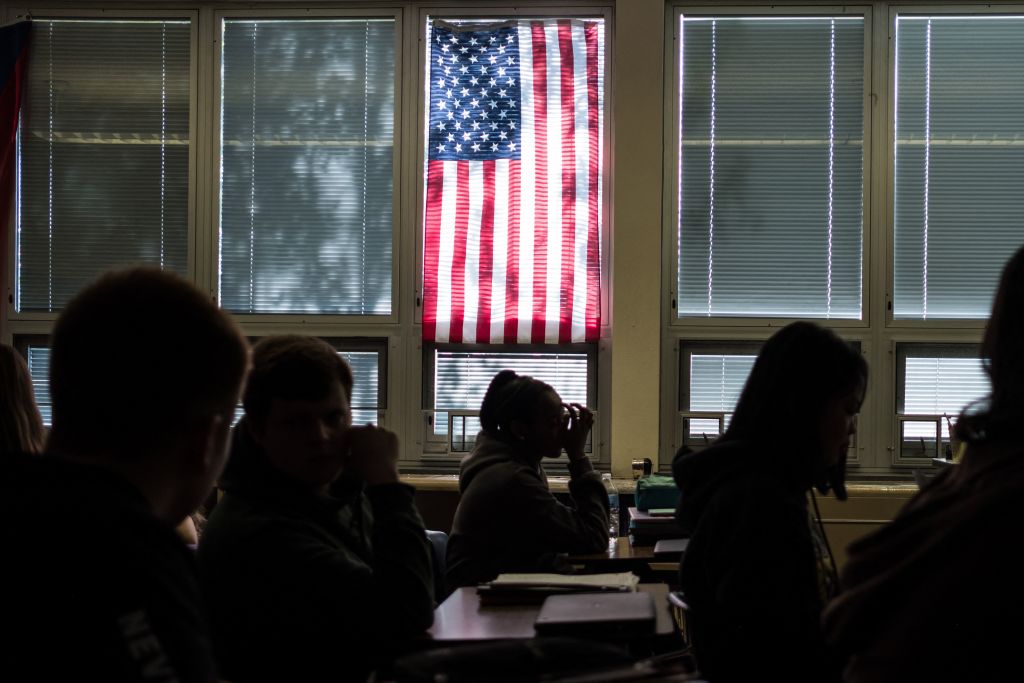

His work has upended a consensus among classical liberals and conservatives that has endured since the 1960s – that the answer to the left’s long march through these institutions was to retake them or push them to admit more right-of-center voices as professors and campus speakers, not engage in a campaign to tear them down. Rufo’s approach casts this aside for something more akin to Bane’s solution for Gotham: a reckoning.

Rufo recalls a student protest on behalf of cafeteria workers during his time at Georgetown in the early 2000s, which he attended with the intention to go into international politics for the next Democratic administration. “I remember going to this hunger strike and thinking: ‘This is a noble cause,’” Rufo says. “But then I was talking with some of the actual cafeteria workers, which no one else seemed to have done. And I realized that they were just embarrassed by the whole theater show. They didn’t want anything to do with these hyper-privileged kids dressed up in revolutionary outfits. And they were really actually scared that not only would this hunger strike fail – which of course it did – but that it would actually put their jobs at risk. It was like a reenactment of the civil rights movement [led by] all of these kids who are going to go into banking and consulting, white-shoe law firms and high finance.”

The experience caused in him “a cultural and personal revulsion from what you would think of now as the left’s professional managerial elite. I had this extremely strong feeling that the entire enterprise was preaching high-minded ideals but, in reality, was just a kind of ruthless and empty status-seeking.”

While filming a documentary about hardscrabble life in America for PBS, which looked at the struggles of life in the cities of Youngstown, Memphis and Stockton, Rufo became more interested in questions surrounding the failure of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. He turned to conservative literature, reading Charles Murray’s Coming Apart along with Robert Nisbet, Thomas Sowell and Shelby Steele, and finding in their descriptions of American life a greater understanding of the failure of the same professional managerial elite he knew from his college years – and not just on the left.

“I maintain a good relationship with most of the institutions [of the right],” Rufo says. “I think almost all of them are well-intentioned. And many of them have contributed greatly to the movement in general, and on the particular challenge of education. But what I would say is lacking, as a general matter, is not the mind, but the hand. Conservatives have imagined that politics is predominantly about intellect – developing the right philosophies or making the stronger argument with facts and logic. But what I’ve learned in practice and also in the study of history is that the good ideas don’t always win. Bad ideas often win. So you have to ask yourself not just ‘Have I adopted the right principles?’ You have to ask yourself, ‘What can I do to advance or maintain those principles?’ And I think the answer to that question is you have to do politics, and that requires courage, strength, bravery, action, conflict, controversy – all things that many conservative intellectuals are just temperamentally unequipped for.”

This aggressive stance toward pursuing dramatic change has gotten results. Rufo’s campaign against former Harvard president Claudine Gay, spurred on by her stunningly tin-eared performance in a House hearing on anti-Semitism on campus, led to the exposure of nearly 50 instances of plagiarism and citation flaws in her work across multiple papers and her dissertation – and ultimately to her resignation. When Rufo identifies a target, he doesn’t hold back – even if that target is sometimes seen as being on his side of the ideological fray.

“I’ve gotten calls and texts from various people who are all well-intentioned, saying, ‘Hey, you should really lay off.’ I’ve challenged a number of highly respected conservative or classical liberal figures in academia, people like Jeffrey Flier at Harvard Medical School, Alex Tabarrok at George Mason University, Robert George at Princeton University. All these individuals, in theory, have mostly aligned principles with me. But all of them have offered criticism of the work that I’m doing.

“What I have really tried to raise in reply is, it’s very easy to say ‘I’m a principled conservative and I have all of the right ideas, and this is how it should be.’ But the actual test is, well, did you get those ideas into power at your own institution? The answer in all three of those cases is no.”

Rufo’s larger purpose, as he sees it, in every aspect of his work – whether as an online fomenter of dissent or alongside Florida Governor Ron DeSantis at the New College of Florida – is to bring the American right into a new headspace. He hopes to impart to them an understanding that they cannot allow the institutions captured by the left to define them out of the conversation, or limit them in their use of power.

“I think conservatives have really delegated their own perception of their own self-worth to their enemies – that you have to be legitimized by the New York Times and Princeton University,” Rufo says. “My big fight is to actually deny the legitimacy of America’s elite institutions, to deny my enemies the power to define how I see myself.” Yet there is still a limit here for Rufo: this doesn’t mean, from his perspective, burning down the very concept of American elites.

“What does burning down the elite or having an elite-less society or a classless society do? It starts to sound like a kind of Marxist utopia. It was impossible in 1775, and with the proliferation of a complex economy and complex institutions and complex knowledge production, it’s even less possible now. So the only responsible position is to say we either capture the elite, or at least we capture the values of the elite so that we reorient how people think.”

During Donald Trump’s second term, Rufo has gone from outsider to insider. His ideas are being applied not just because he forces issues into the public square, but because there are key people in positions of power who agree with his thesis and are ready to put it in motion via policy.

“Our federal government is already the most powerful institution in the country and arguably in the world. We are already using this power as a people, as a government, as a state. And I think conservatives who insist, on principle, that the use of power is somehow always corrupting are not recognizing the status quo, which is that the current organization and orientation of power in the United States has been corrupting for the past century,” Rufo says.

“And so the question is: what to do about it? I think that the fantasy that we can have a libertarian nightwatchman state sounds wonderful. But even if we agree that that’s the goal, how do we get there? What do we have to do in the meantime? That’s a harder question. And you can’t just retreat to abstraction.”

When asked about Allan Bloom’s 1987 book, The Closing of the American Mind, Rufo calls it a “cultural touchstone” that “really set the stage for what’s happening now… that moment come to full fruition.” But he also identifies in it some of this same unwillingness to wrestle with the need to enact radical change – change he now views as possible. “The book was this massive cultural moment, then America kind of fell asleep on the academy for a generation. And now it’s back.”

What Rufo sees in American conservatism at the moment is a debate in which leading figures are “driven to apoplexy about liberal versus illiberal, and the assumption that anything liberal is good and anything illiberal is bad. I think it’s the same question of an open and closed mind.

“I think one of the problems is that our minds have been too open, that our brains are spilling out. And so part of the mind should be closed a bit more. Part of the mind should be opened a bit more. Part of our society should be a little bit more liberal. Part of our society should be a little bit less liberal.”

He adds, with a firmness that suggests he would not be unafraid of that UFC octagon after all: “We all play the game. I play the game and I recognize that I play the game. When I go at it in these campaigns, I truly want to win and I want to win in a material way, not just an abstract way. I’m convinced that you have to win materially. Moral victories are just a rough consolation.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply