I stepped through a hole in the chainlink fence surrounding Portland’s O’Bryant Square and saw four people nodded out and three smoking fentanyl. The man who had supplied them was standing nearby; he gave me a nod and continued with his business.

Built in 1973, the park is mostly brick and concrete with its dominant feature a bronze fountain in the shape of Portland’s iconic rose. It was permanently closed and fenced off in 2018. The city blamed “structural issues,” but the real reason for closing the park was that it has long been a well-known place to use drugs. As a teenager in the late 1980s I used to skateboard there. As I practiced ollies, I often observed LSD and marijuana deals.

I’ve been a drug and alcohol counselor and outreach worker for almost thirty years, so I’ve witnessed drug-use trends up close: the crack epidemic, the rise of heroin, then ecstasy, then meth. These are drugs that my colleagues and I researched extensively. They all brought their challenges and we found ways to help. But all this experience could not prepare us for the arrive of fentanyl.

Fentanyl was introduced in the 1960s as a legitimate intravenous anesthetic to treat patients experiencing severe pain. If you’ve had surgery in the past several decades, or even an epidural when you were having a baby, you may very well have been given it; it’s very good at what it does. Then drug cartels learned how to manufacture it cheaply and on a massive scale and it spread faster than anything I had seen before, starting around 2017. Now it plagues the streets of America’s cities and cuts a deadly swath in rural areas as well.

Fentanyl is fifty times stronger than heroin and ruthlessly addictive. What starts as a desire to use quickly becomes something more desperate. Clients describe to me spending every waking moment hustling to get enough pills for the day. When I ask them where they see themselves in a week, a month, a year, they can only describe today. They are entirely entwined in their addictions and can only see a few hours ahead — to their next fix.

The most common way to use street fentanyl is by placing a pill on a piece of tinfoil, heating the foil with a lighter and inhaling the smoke through a plastic, glass or metal straw. The effects, I’m told, are euphoric — many of my clients describe using the drug as feeling like they are closer to God or to Heaven. The effects last about an hour and a half, meaning a heavy user must smoke several times a day to avoid withdrawal. A homeless man recently described the discarded foil he saw all around him as “blowing like autumn leaves.”

Addicts tell me fentanyl has changed everything. It is cheap and extremely potent. Its effects are unlike anything else they have ever experienced. As a homeless woman sitting on a log behind a convenience store underneath a large “No Loitering” sign explained to me, “When I first tried ‘blues’ [a nickname for fentanyl] everything changed. I found something cheap that made me closer to God.” Another told me he became addicted after accidentally using meth laced with fentanyl. “Something was different. I felt more alive. Better than I thought possible. I’m different.”

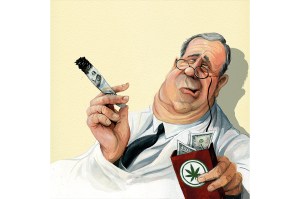

But while addicts recognize fentanyl to be a gamechanger, our policy response does not. In response to this deadly new street drug, the official response, from the city to the federal level, has been to stick with the logic of harm reduction – the idea that the goal should be reduce the damage done by drug use rather than treat and cure addiction. In reality, this response means making more posters and manufacturing more straws, and more foil. It’s like putting a Band-Aid on the arm of someone with cancer and thinking you are treating them. It ignores the real problem and will never cure them.

Walking through O’Bryant Park that day, I noticed graffiti and far-left activist propaganda — “ACAB” (All Cops Are Bastards), “die pigs,” “fuck Ted Wheeler,” “votes don’t work,” “stop the sweeps,” “kill Andy Ngo” and so on. I approached the first person who made eye contact. Wearing a t-shirt that read “I’m with Spooky,” he was leaning against the brick steps, his head nodding up and down as he struggled to stay awake. I sat next to him, he perked up and we started talking. He called himself “the Dragon” and said the fun of using fentanyl has worn off but he uses it several times a day because he’s afraid of getting dopesick. He told me he started using it to “most definitely drown myself in my own sorrows.”

I asked him if anyone in the community was helping him; he mentioned he regularly gets “harm reduction” supplies from the nearby clinic, including new straws, foil and Narcan, an opioid blocker, in case he overdoses. I asked if they had ever offered other services such as help getting clean, help for depression or help getting off the streets. He seemed confused by my question but said, with a smile, that he had a right to use, to not be judged about it, and that it was his body and his life. I thought, “What kind of life is this?”

Early in my career, harm reduction was mostly about needle exchange for heroin addicts, to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS. But in recent years, the term has come to stand for a more radical set of ideas. The primary focus of harm-reduction advocates is now on social justice and bodily autonomy. When it comes to drug addiction, the idea that people have the right to make decisions about their own bodies (up to and including suicide) without coercion from anyone else means supporting the right to use without judgment or intervention. A recent, now infamous, harm-reduction poster sponsored by the New York City Health Department depicts a smiling woman alongside the words, “Don’t be ashamed you are using, be empowered you are using safely.” Another shows a group of five friends sitting closely together, smiling and laughing. It reads, “Change it up. Try ingesting or smoking instead of snorting.”

Is this really helping? I entered social services to make a difference, to help people break the cycle of addiction, to give them hope again and to help them recover, not to encourage bad behavior or suggest that clients deep in addiction keep using.

A few months ago I spoke to the executive director of a national harm reduction program. She admitted that fentanyl is deadly, but said she believed that offering addicts services to help them get clean would “ruin the trust.” She told me it was best to “sit quietly” when our human instinct to save a person kicks in and to “absolutely not say a word.” I told her that, when it comes to fentanyl, her preferred approach is like handing a Russian roulette player a gun with six bullets. “Everyone has to make choices and sometimes those choices lead to death,” she replied. She seemed very sure of her assessment; it was obvious I wasn’t going to change her mind.

After Dragon finished talking to me in the park, he moved to the end of the fountain to sleep. Nearby I met two young men in their early twenties. They had both been homeless for a few years and admitted it was their drug use keeping them on the streets. Randall, clutching a piece of tinfoil and a straw, told me he switched to exclusively using fentanyl after using used heroin laced with it. He told me he believes the drug is going to be the end of people and the start of a “zombie apocalypse.” His using-supplies come from the nearby harm-reduction clinic. He agrees that they are “strangely optimistic” about drug use, but feels good being there and refers to them as family. “They are like a family you love, despite knowing I am killing myself,” he said with a smirk. His friend Superman (as his t-shirt attested) was less positive. He said the clinic would never help you get clean and that while sometimes he appreciates being left alone and allowed the freedom to use, “sometimes I wish they would try.” He finished by calling fentanyl “a weapon of self-destruction.”

Despite knowing how dangerous fentanyl is many continue to use it to calm anxiety and sleep. Last year I met a young female addict with scabs all over her face who told me that fentanyl is her medication. She first learned of fentanyl from a poster in the harm reduction clinic. She described the first few “warnings” she remembers seeing that did not sound like warnings at all. I went to the clinic and found the poster. The first word was analgesia, meaning pain relief, followed by sedation, euphoria, relaxation and pupil constriction. Considering the state of most homeless people, often struggling with severe anxiety and trauma, reading words like “euphoria” and “relaxation” isn’t a warning, but an invitation.

Last year saw a record number of overdose deaths in America, most of them from fentanyl. We are, tragically, trending even higher this year. Harm-reduction activists assure us they are saving lives, but what they are doing is convincing impressionable addicts that there is nothing wrong with using, and encouraging them to feel empowered, liked and accepted when using. If an addict thinks of fentanyl as a weapon of self-destruction then harm reduction turns out to be a weapon of mass destruction. When we see a person suffering, teetering on the line between life and death, we have a responsibility to help, not to respect their “bodily autonomy.” Where do we go from here?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2023 World edition.