Firefighters do not run into a blaze like you see on TV. We crawl with purpose like rats in a maze, which is what a well-involved structure fire feels like, the smoke so thick our high-powered flashlights can’t cut through it. We are trained to locate windows and leave furniture in place as reference points while we conduct search and rescue then scurry to the nearest walls. It makes it all the more vital to have another firefighter with you.

The fire was consuming a construction site on Yale’s campus. “The security guard’s inside.” The water company hadn’t arrived yet. No matter, we were going in. I ordered the firefighter to grab the forcible entry saw. He didn’t know where it was. Precious seconds gone. I found it myself and cut my way in. “Let’s go.” He wouldn’t. I went in alone.

The next morning’s Yale Daily News was optimistic: the fire would not prevent students from moving into the dorm that fall; only three firefighters were hospitalized. They didn’t ask who or why. I fell fourteen feet down that stair shaft obscured by smoke. I would have died there had a captain from another fire company not fallen on me. He still calls me “Cushion.”

The man who abandoned me to that shaft owed his job to disparate impact, a legal concept that places all hiring and recruiting at the mercy of statistics. Disparate impact mandates that if a favored class of people fails a test, it is the fault of the test rather than the test-taker. DEI is not a modern phenomena but a direct consequence of disparate impact. On Wednesday, Attorney General Pam Bondi announced that the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division would no longer sue fire and police departments to force them to hire underqualified candidates into their ranks.

The harm that DEI has done to public safety cannot be overstated. For decades fire departments have been sued by women arguing that the job requirements focus too much on physical aptitude. The same trial lawyers then turned around and sued because the fire department’s exams focused too much on mental acuity when it comes to minority hires. The only consistency in a disparate impact case is that the fire department must sacrifice public safety for the sake of politics. There will be no cushion to break the fall.

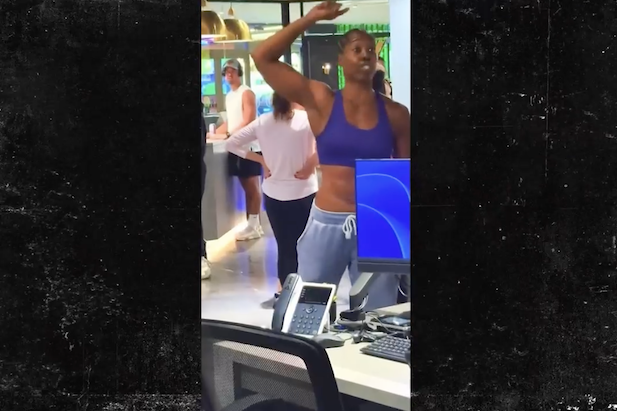

Common sense crept back into the fore before Bondi’s announcement, but it took a tragedy. The Los Angeles wildfires showed the incompatibility of operational readiness with the LA Fire Department’s focus on DEI. Chief Crowley siphoned millions of dollars and countless hours from the budget, diverting resources from the critical missions of life safety, incident stabilization, and property conservation. HR departments seem more preoccupied with diversity metrics than they are ensuring candidates possess the physical strength, mechanical aptitude and cognitive skills essential for emergency services. LAFD assistant chief Kristine Larson, in a recorded statement, responded to a query about her ability to rescue someone from a fire by saying, “Am I able to carry your husband out of a fire? Well, my response is he got himself in the wrong place if I have to carry him out of a fire.” I was forced to attend enough DEI classes during my firefighting career to recognize victim blaming when I see it.

Department of Justice prosecutions played an outsized role in the weakening of public safety for political goals. The Trump administration recognizes this trend is not isolated to Los Angeles. Fire departments nationwide took note when the George W. Bush administration launched an investigation into why the FDNY’s firefighting exam did not yield enough minority and female applicants. Federal attorneys, some of whom may have spent time living in the dorm I nearly died in, have dismissed our concerns as abstract bias rather than the reality that a fire does not discriminate.

Leave a Reply