This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

What would a Michael Bloomberg foreign policy look like? A total smoking ban across the Middle East seems imminent, even if it does risk spawning a new generation of pro-hookah jihadists. Fresh sanctions would likely be imposed on enemies of the West, including Iran and salt. Air superiority would be prioritized, especially as it pertains to illegally landing one’s personal helicopter in midtown Manhattan.

Beyond that, it’s anyone’s guess. Bloomberg has spent most of his career codifying class snobbery through petty regulations, and, while that’s a potent recipe for being annoying at home, it doesn’t really lend itself to a coherent agenda abroad. Perhaps also curious, the New York Times recently asked Bloomberg which world leader he admires most. His answer: Emmanuel Macron, whom he has praised for running a ‘stable government’. This isn’t technically true — Macron is so controversial that French firefighters are literally self-immolating in protest of his policies. But what Macron does do is to cut a figure of what elites like Bloomberg think a leader is supposed to look like, which they then conflate with stability. Crucially, Macron isn’t Donald Trump. Better yet, he subscribes to the liberal internationalist consensus that Trump rejects and has sought to curb.

So perhaps we can say this much about a Bloomberg Doctrine: it would be defined, at least in part, by its opposition to Trump. That might sound familiar — the same theme runs through the foreign policies of most of the other Democratic candidates as they weave through debate answers about Iran and Hong Kong. It’s an irony of the current presidential race that in trying to distinguish themselves from Trump, his opponents have become dependent on him for antithesis. If he’s for it, chances are they’re against it, and vice versa. In fact, to the extent that there is a Democratic foreign policy in the year 2020, it’s this: everything Trump does is wrong, including the things that are right.

This is most clearly seen in the current Democratic hostility towards Russia. Once upon a time, Democrats were eager to leave the Cold War in the past. Hillary Clinton had her famous (and famously mistranslated) ‘reset’ button, which she presented to the Russian foreign minister in one of her first acts as secretary of state. During the 2012 presidential campaign, President Obama ridiculed Mitt Romney for claiming Russia was America’s ‘number one geopolitical foe’, snarking: ‘the 1980s, they’re now calling to ask for their foreign policy back.’ (Even when he had a good line, Obama always seemed to chew on it a bit too long.) After Russia invaded Crimea in 2014, Obama’s response was largely restrained. Speaking later with the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg, he came off as a coldhearted realist, sighing that Ukraine ‘is going to be vulnerable to military domination by Russia no matter what we do’.

But that was before the Russians purchased $100,000 in pro-Trump Facebook ads, and before the Kremlin became a fig leaf behind which Democrats could hide from the policy failures that motivated voters in 2016. Today, the left views Russia as a kind of 11-time-zone-sized MAGA hat, a sprawling Trumpistan where right-wing authoritarians scheme under sinister onion domes. Trump has replaced Marx as the prism through which Moscow is seen, and the Democratic candidates have responded accordingly. Pete Buttigieg characterizes Russia as awash in ‘nationalism, xenophobia, homophobia, and the repression of the press’.

Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, ever a fan of doomed interventions into hostile territory, recently barged into the Democratic primary to announce that Tulsi Gabbard, the candidate most committed to peace, was being ‘groomed’ by the Russians. That Clinton wasn’t immediately laughed out of polite society shows just how far her party has gone. To be fair, the Democrats are hardly calling for nuclear war with Russia; many of them, Joe Biden leading the way, support an extension of the New START arms control treaty and other diplomatic initiatives. Still, the road from Obama-era optimism to present bellicosity is a long one, and it’s been paved by Trump, whose perceived coziness with the Kremlin — nonsense though that might be — has greatly shifted Democratic thinking.

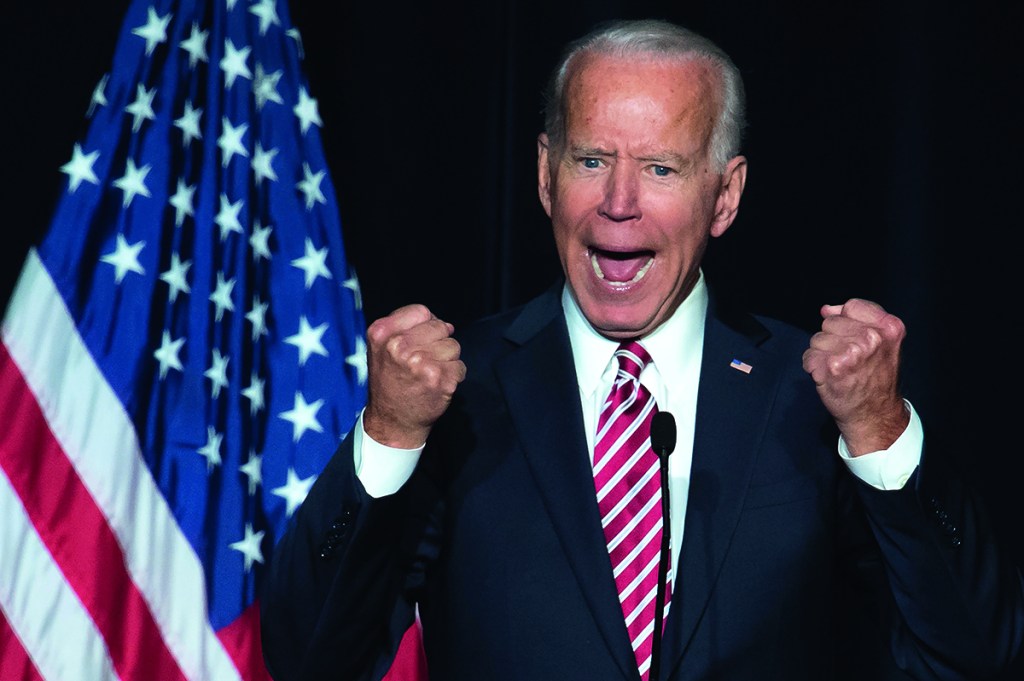

According to Bernie Sanders, it isn’t just Vladimir Putin we have to worry about, but a veritable archipelago of ascendant authoritarians, including ‘Xi in China, Mohammed bin Salman in Saudi Arabia, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Viktor Orbán in Hungary’. (Strangely Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela didn’t make the cut.) Sanders’s list sounds a bit like an axis of evil; what he means it to be is an axis of Trump. This theme of creeping global Trumpism was expounded upon by Joe Biden in an essay for Foreign Affairs, where he fretted that democracy is weakening across the globe, while dictatorship and ‘fear of the Other’ are metastasizing. The solution? The democracies of the world need to rally, with America reclaiming her natural position in their vanguard.

It’s the stuff of global ideological competition — the 1980s seem to have us on speed dial — only this time the forces of light are good liberals while the Iron Curtain enshrouds Trump, Putin and their confrères. And because Democrats think their policies are synonymous with democracy — even when they’re deeply elitist — and because democracy is seen as a global good, their domestic program gets rolled into their foreign policy, with raising the minimum wage just another way of safeguarding democratic values abroad. Thus does Biden recommend a ‘foreign policy for the middle class’, which will do everything from demolishing trade barriers to providing universal health care to assenting to the Paris climate accords. The sine qua non is stopping Trump, the left’s new enemy both foreign and domestic.

Another authoritarian regime Sanders might have listed is Iran, yet here the Democratic position becomes more nuanced. For one, Barack Obama signed a nuclear deal with Tehran, and after Trump pulled America out of it, Democrats united behind it. For another, Trump has an odd militant blind spot when it comes to Iran, which has forced the left, aligning themselves against him, into a more dovish stance. Democrats are thus more measured in their denunciations of Iran than they are of Russia, even as the ayatollahs sanction thuggish beatdowns of protesters and condone the execution of gays.

All the 2020 hopefuls agree that Iran should not be allowed to acquire a nuclear weapon. But Trump’s assassination of Qasem Soleimani proved a point of divergence among the Democrats. Biden warned that Soleimani’s killing ‘takes us a heck of a lot closer to war’ and refused to give Trump the benefit of the doubt over his claim that Soleimani was plotting imminent attacks on American forces. Elizabeth Warren was more direct, accusing Trump of a ‘reckless move’ that ‘increases the likelihood of more deaths and new Middle East conflict’. Soleimani’s demise became an opportunity for Democrats to pump up their antiwar credentials, even as this led them into a state of mortal sin: agreeing with Russia, which also condemned the killing. For a fleeting moment, it was 2004 all over again, with a Republican administration urging real men to go to Tehran, while the left, along with much of the world, looked on in alarm.

Yet two months earlier, when Trump had made another impactful move in the Middle East, the roles were reversed. That was when the President abruptly decided to withdraw American troops from northern Syria, and the Democrats reacted as though he’d just cosigned the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Biden declared Trump to be a ‘complete failure’ as commander-in-chief, while even the reliably antiwar Sanders denounced the move. America was said to have sold out its ally, ceded ground to its adversaries, undermined its credibility. The Democrats were in agreement with pro-war neocons while Trump was accused of cutting and running, the opposite of the Soleimani aftermath. We must end forever wars, except when Trump tries to end them. We must support democracy abroad, except where Trump still has troops. Such needles are too finely threaded to be about anything other than politics. And such rhetorical gymnastics are too confounding to follow without an industrial-grade funnel in one hand and a bottle of vodka in the other.

None of what the Democrats are doing here is new. Foreign policy, being a niche specialty, is often subordinated to political tribalism, as it was when John Kerry tried to portray himself as a dove-cum-dovish hawk in 2004 and George W. Bush postured as an opponent of Clintonian imperialism in 2000. And it’s not like the Democrats don’t have anything valuable to say on the subject. Biden has repeatedly repudiated his vote for war with Iraq. Warren shines when she upbraids the military-industrial complex. Sanders remains invigoratingly antiwar, even if he always colors in bright pastels.

But for those of us who want a real rethink on foreign policy, who were disappointed when Trump failed to make that happen, the Democrats don’t offer much in the way of confidence. Yes, there is a dovish current coursing through their rhetoric, but it’s too often undermined by that instinctive hostility towards the President and the illiberal bloc supposedly rising globally. It isn’t such a long path from ‘we must defend democracy abroad’ to ‘send in the bombers’ — witness liberal savior Macron deploying troops from Syria to the Sahel. The Democrats, then, have some work to do if they’re going to present a real alternative. There is, of course, one exception: queen of the islands, scourge of the Straussians, ku’uipo of the kompromat, Tulsi Gabbard. The Hawaii congresswoman hasn’t just been consistent in her opposition to stupid wars; she’s attacked, often by name, the neoconservatives and neoliberals who have brought America to the brink of imperial ruin, including those in her own party. And while she doesn’t like Trump, she seems to take a longer view of his presidency than most of his other critics. For that, she’s been smeared by Hillary Clinton as a Russian asset and excluded from CNN’s town halls. She isn’t a prophet like Macron, to be sure, but on foreign policy she does embody another P-word that gets clanged around a lot: no, not Putin — progressive.

This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.