Recently, a friend of mine found himself having a bad day for a reason I now forget. I made a lousy attempt to cheer him up. “Omnia in bonum,” I said to him – all things work together for good. The Latin phrase has served as a salve for me in hard times. Little did I know that I had just made things much worse. He was visibly shaken. I asked him what was wrong. I had unknowingly stirred memories of his parents’ difficult and traumatizing divorce, during which that same phrase had been used by them in a pointless attempt to assuage their children’s sadness.

The idea that a phrase, a memory or an object can be simultaneously cursed for one person and blessed for another had never occurred to me. It has occurred to the Finnish filmmaker Joachim Trier. In his most recent feature, Sentimental Value, the Borg family home in Oslo is a haunted place for some and a beloved object for others. For some, it is imbued with the memory of a mother’s suicide; for others, with the happy memories of family life before a divorce. The house has a structural crack that threatens to bring down the entire edifice – much like the family.

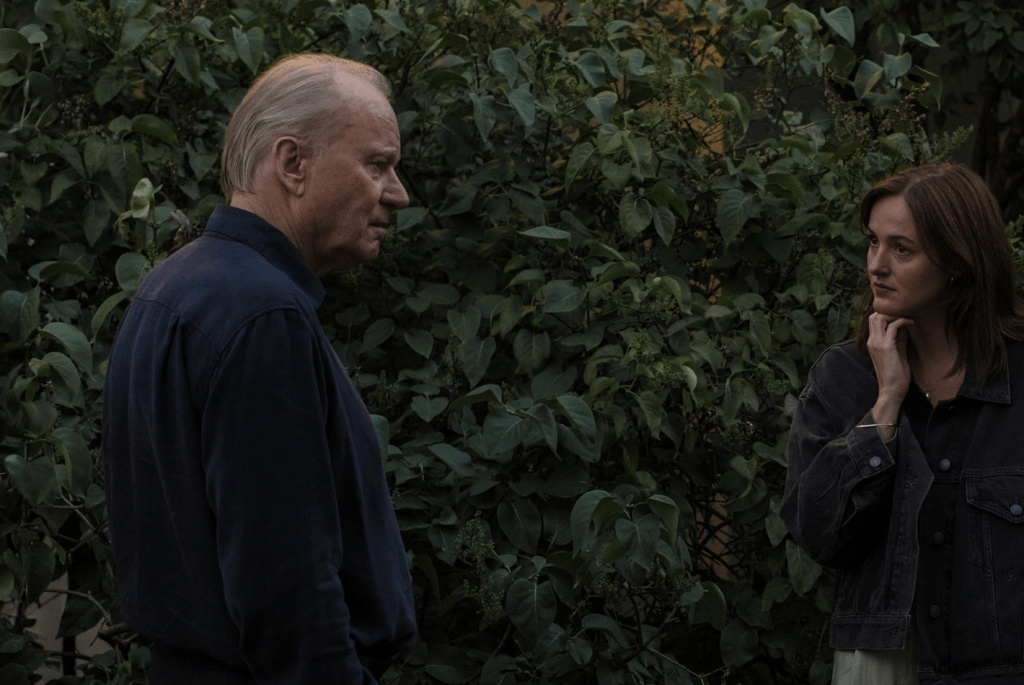

The film follows Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård), a once-celebrated film director, who, after the death of his former wife, attempts to reconnect with his estranged daughters Nora (Renate Reinsve) and Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) by making a movie based on the life and death of his own mother. He attempts to recruit Nora, now a successful but troublesome stage actress, to play the leading role. Once she refuses, he strives to find a suitable replacement, fixing on American superstar Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), although he has clearly written the role for Nora.

Stellan Skarsgård stands out. His role as Gustav is a career best. The film, in more ways than one, falls on his shoulders. He’s an actor who’s become so ubiquitous that we seem to have forgotten how good he can be. Though he has in recent years taken to playing menacing villains, here he embodies a vulnerable, tortured artist.

Trier, who first gained international acclaim for The Worst Person in the World (2021), is concerned with the nature of art as a medium for connection and understanding. Art is frequently promoted as an instrument for communion and empathy. Whether true or not, arguments in favor of this happy view regularly take the form of new-age gibberish. “True art is about empathy and bringing us into the world of others,” we’re told. But what does this process actually look like?

After years of estrangement, Gustav’s attempts at reconnection – accompanied by seemingly trite and forced shows of affection – are viewed with suspicion by Agnes and rejected outright by Nora. “I recognize myself in you,” he tells his daughter. To which she replies that he does not even know her.

Can we know someone as he truly is? Through the writing of his film’s script, Gustav strives to empathize and understand his mother’s depression and eventual suicide. “Why did she do it? What could she have possibly been thinking?” How does one reach such levels of despair? Gustav’s script depicts the beautiful prayer of a woman to a God she’s not even sure exists. She calls God into the dock, and receives only silence as a response. Unbeknownst to Gustav, this scene closely resembles Nora’s personal experience with depression, which eventually led to a suicide attempt.

Compassion is a sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress. In art, however, as in life, compassion must go much deeper than mere awareness of another’s pain. It draws us to “suffer with” or to share in someone else’s passions. Through his journey to find answers to his own life, which was deeply affected by his mother’s depression and suicide, Gustav is unwittingly drawn into Nora’s own depression. After realizing that Rachel Kemp is not the right fit for the part, the future of the film is threatened. He has his own brush with despair, suffering as Nora has suffered, further deepening his connection to her.

After reading the script, Nora accepts the role. Living out the script that Gustav has written makes her see the house as he does. Acting allows her to do what all art should do: to see the world through the author’s eyes. In this film, Gustav and Nora play out the roles of artist and spectator.

And yet, the crack remains. It’s clear that art won’t completely seal the gap between father and daughter. Trier does not idealize the role of art. Fundamental differences between individuals are ever-present. Art cannot, as through magic, bridge all the gaps and fix all the cracks. Art initiates a process of offering consolation, if not resolution, which is all we can hope for. Through art, the family, like the house, though divided, still stands.

Leave a Reply