Seventy-five years ago this week, Clement Attlee became prime minister of the most radical government in British history. In office, Attlee faced unprecedented problems created by the need to turn a near-bankrupt wartime economy back to the requirements of peace while finding work for millions of demobilized soldiers. Under his leadership and despite these problems the Labour administration nationalized 20 percent of the economy and created a cradle-to-the-grave welfare state, one his Conservative opponents said the country could not afford. At the heart of this new welfare state stood the National Health Service, which guaranteed free healthcare to all in need.

During the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher reversed many of Attlee’s economic reforms but even she, through gritted teeth, had to publicly promise that the NHS was safe in her hands. Thatcher was enough of a pragmatist to recognize that the NHS was one of Britain’s most popular institutions. Today it remains more highly regarded than the royal family. Some even claim the NHS has become the country’s ‘national religion’ and it certainly shapes how many Brits think of themselves and their nation, most notably expressed in the opening ceremony to the 2012 London Olympics. The COVID crisis has only strengthened the emotional bond between the British and their health service.

It is probably principally for this reason that, when historians and other informed observers are asked who was Britain’s greatest Prime Minister, Attlee is often ranked first — and rarely lower than third. But who cares for experts? In terms of popular thinking, it is Winston Churchill — the man Attlee replaced in No. 10 in July 1945 — that many Britons regard as their country’s most significant historical figure. Most egregiously, when in 2002 the BBC asked the public to name the Greatest Briton, it was Churchill who came top while Attlee — unlike David Beckham, Bono and Bob Geldof — did not even make it into the top 100.

Given he helped ensure Britain fought on against the Nazis in the summer of 1940, Churchill’s position as a central character in modern British history is undoubtedly justified. It was the moment in which Britain played a uniquely critical role in international history: had the country buckled, the world would be a very different and even darker place. But if Churchill made Britain safe from Hitler, Attlee made Britons safe from the dire consequences of ill-health, the fear of which gripped all but the most well-off.

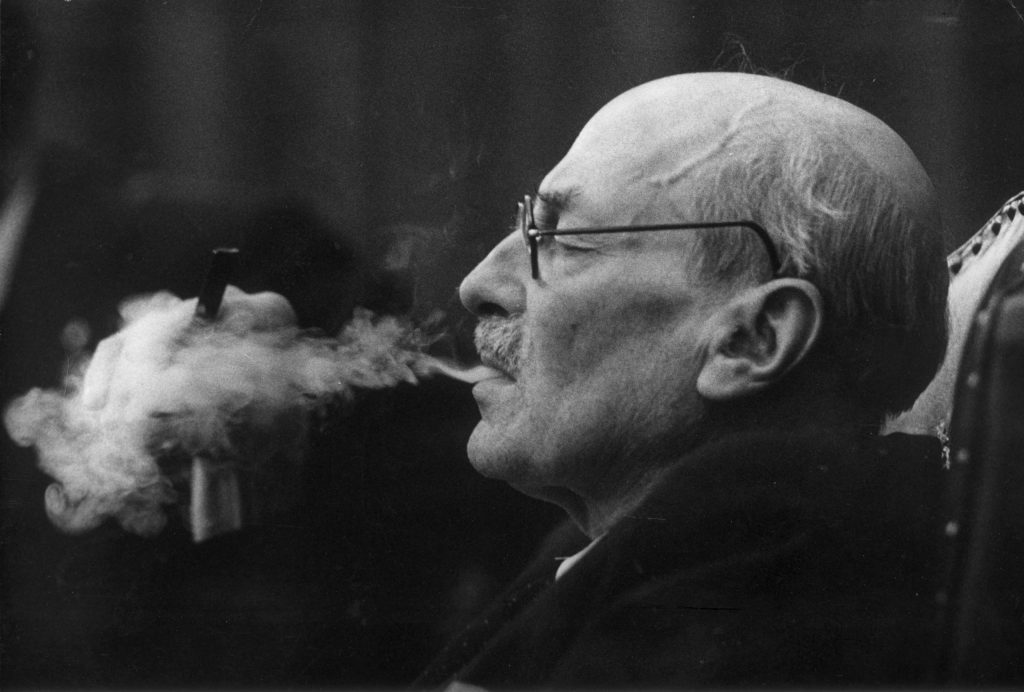

Churchill and Attlee are, then, comparable in terms of their historical significance. To make this point Leo McKinstry recently wrote a dual biography of the two figures. But his was a rare attempt. For the most part, in terms of biographies, TV documentaries, biopics and statues, Churchill beats Attlee hands down as a figure who is repeatedly memorialized. Indeed, I have co-written a book which attempts to account for the complex and multifarious ways in which Churchill has been mythologized, to such an extent during the 2016 Brexit campaign both Leave and Remain claimed him for their side. But no similar book could be written about Attlee: the material is simply not there. In contrast to Churchill, Attlee has failed to become a figure of popular national significance.

Churchill’s prominence owes something to his facility with words: ‘History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it’ he once said. And if Churchill is famous for his rhetoric Attlee is best known for his lack of it, which together with his modesty was not exactly an advantage when it came to establishing a popular reputation. But the former’s stature also says much about many Britons’ continued regard for martial virtues as the purest expression of their national character rather than values more associated with nurturing, as embodied in the NHS. How many films, for example, have been produced about World War Two compared to the making of the health service? There is, to make an obvious point, no equivalent to the 1955 film The Dam Busters and Eric Coates’s theme tune that will be familiar to millions.

[special_offer]

Critically, Churchill was also adopted by Americans who — especially after his 1946 ‘iron curtain’ speech — saw him as a useful soldier in the gathering Cold War, especially as they could draw parallels between his opposition to interwar appeasement and warnings about Stalin’s post-war ambitions. By contrast, many in Washington saw Attlee — despite Labour’s leading role in forming Nato — as the unwelcome progenitor of ‘socialized medicine’. There has therefore never been a bust of Attlee in the White House, nor Hollywood cash for an Attlee biopic, while we have yet to see an equivalent of the transatlantic International Churchill Society.

It is, then, culture more than actual achievement that accounts for Attlee’s popular obscurity. And, for that, Attlee is partly to blame. For while his government wrought, to the eyes of some, an economic revolution, it left the leading institutions of British national life — private schools, grammar schools, Oxbridge along with the BBC and the monarchy — untouched and in the hands of the pre-war traditional elite. Scion of Haileybury and University College Oxford, Attlee called himself a socialist but was deeply imbued with conventional upper middle-class values. His Labour party was economically radical but culturally conservative and unwilling to challenge the forces that would ensure it was Churchill who emerged to be regarded as the country’s leading national figure.

History never repeats itself. But today Labour’s Keir Starmer — whose (lack of) charisma some see as Attlee-like — confronts a Conservative party led by someone who fancies himself as having a touch of Churchill about him. Starmer also faces calls to make his party more culturally conservative while remaining economically radical if he wishes to win the next election. Meanwhile, the COVID crisis has made guaranteeing the UK’s health a critical political issue. Will the ghost of Attlee finally emerge out of Churchill’s shadow?

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.