Boris Johnson failed to break the Brexit negotiations deadlock over dinner with European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen on Wednesday night. But while the continuation of talks suggest that neither side favors no deal, something needs to give if a deal is to be reached. It’s here that Germany holds the key.

France appears to be the major obstacle to a deal, particularly over fisheries, but also over the level-playing field. France and the UK have similar-sized and structured economies; both are major military powers and maritime nations. Paris is more likely than Frankfurt to threaten London’s crown.

But Germany — the ever-pragmatic manufacturing titan of the EU — will be the final arbiter of any decision. It is Germany which has frustrated French attempts at transforming the EU into a coherent geopolitical force. Meanwhile, Berlin has a more complex relationship with Russia than the average western European country, while its relationship with China is more influenced by the need to maintain trade ties.

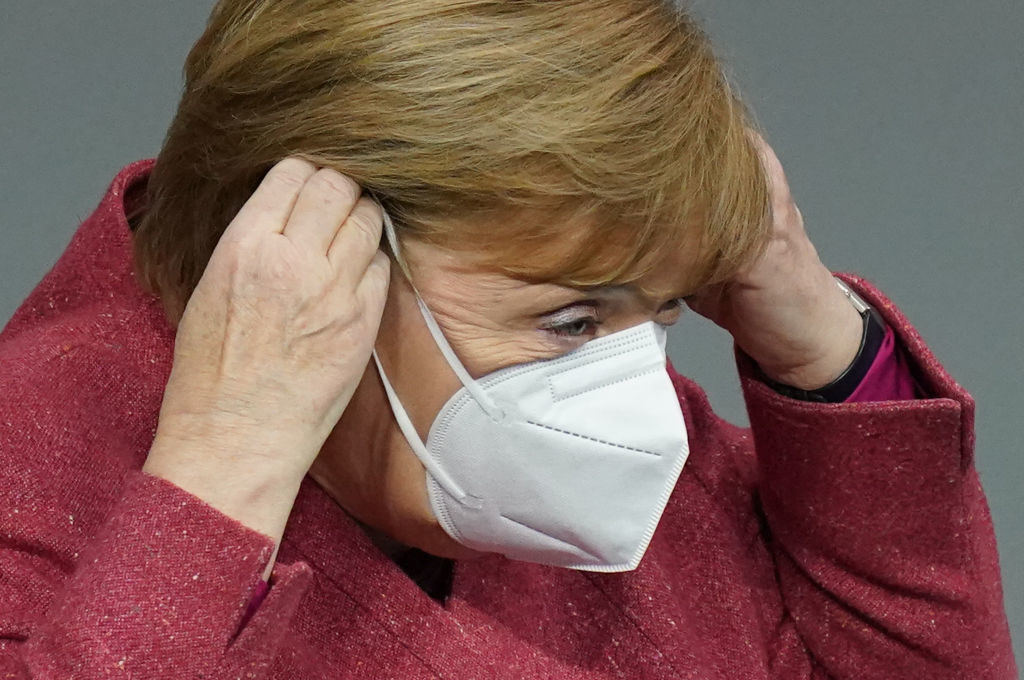

Germany generally acts less in a spirit of passion and principle, so much as reason and pragmatism, even to the frustration of its allies. True, Chancellor Angela Merkel told the Bundestag her Government was willing to let negotiations collapse if Britain continued to reject the EU’s position. But near-landlocked and export-oriented Germany could be unwilling to risk the economic hit to itself or the EU of no deal. Such an outcome could cost the EU €33 billion ($40 billion) in annual exports, with Germany suffering the biggest blow (€8.2 billion or $10 billion), followed by the Netherlands (€4.8 billion or $5.8 billion) and France (€3.6 billion or $4.4 billio).

A recent development is instructive here in showing what could happen over the next few weeks. A revised plan — negotiated by the German presidency of the Council of the EU — now means a solution could be (temporarily) reached between the EU on the one hand, and Hungary and Poland on the other — the latter having objected to tying funds in the EU recovery fund and budget to the ‘rule of law’. Frustration with Hungary and Poland is nothing new. Earlier this year, Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte even asked if a new EU could be created without them. The EU contemplated proceeding with the package without the two countries.

But ever-pragmatic Germany compromised, with the rule of law mechanism set to be delayed. Under a new plan, leaders would approve asking the Commission to refrain from implementing the mechanism while a member state challenges its legality at the Court of Justice of the European Union. The proposed deal would stipulate that the mechanism applies solely to the 2021-2027 budget and recovery fund. This is can-kicking, of course, but the EU has a track record of such things, and Germany knew too much was at stake, both for itself and the bloc.

According to Konrad Popławski for the Center for Eastern Studies — in a paper also published by the University of Pittsburgh — Visegrád countries have actually helped the competitiveness of the German economy. Between 2003 and 2014, the German share in the Visegrád countries’ foreign trade fell from 30 percent to 25 percent. Over the same period, the participation of these states in Germany’s foreign trade rose from 7.9 percent to 20 percent. Germany has been a beneficiary of investments in these states from the EU cohesion policy. Germany knew central and eastern European countries are in relatively strong financial positions, so forcing their hand would not be so easy.

According to the European Commission, GDP forecasts for 2020 suggest that Hungary (-6.4 percent) will fare better than both France (-9.4 percent) and Italy (-9.9 percent), and even the EU27 (-7.4 percent). Meanwhile Poland (-3.6 percent) will fare better than Germany (-5.6 percent).

[special_offer]

In terms of Government debt as a percentage of GDP, Hungary’s figure for 2020 (78 percent) is not only lower than those for France (115.9 percent) and Italy (159.6 percent), but the EU27 as a whole (93.9 percent). Poland (56.6 percent) again fares better than Germany (71.2 percent). While central and eastern European countries are generally net beneficiaries of the EU, even at the highest end the contribution to GDP is around 1.5-3 percent. There is no guarantee the likes of Hungary and Poland will qualify for the same level of funds in the future.

Germany appreciates that the EU cannot afford to isolate Budapest and Warsaw (not yet at least) — potentially undermining the EU even further, especially given Brexit and the coronavirus crisis — nor can it afford to scupper the recovery fund.

Yes, Germany will want to avoid undermining the single market. But if Germany can hold its nose with Budapest and Warsaw, it will likely try to do the same with London, confident that the UK is not really willing to risk no deal. Whether this is in Britain’s interest is another matter. However, it is Germany’s pragmatism rather than France’s intransigence which will likely drive any final decision.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.