When the first shot rang out at dawn on Lexington Green, a decade of frustration and growing alienation between the American colonies and the British government boiled over into armed conflict. By the time the British staggered back into Boston on the evening of April 19, 1775, having fought a running battle for twenty-five miles from Concord’s North Bridge and losing at least 73 killed, the American Revolution had begun.

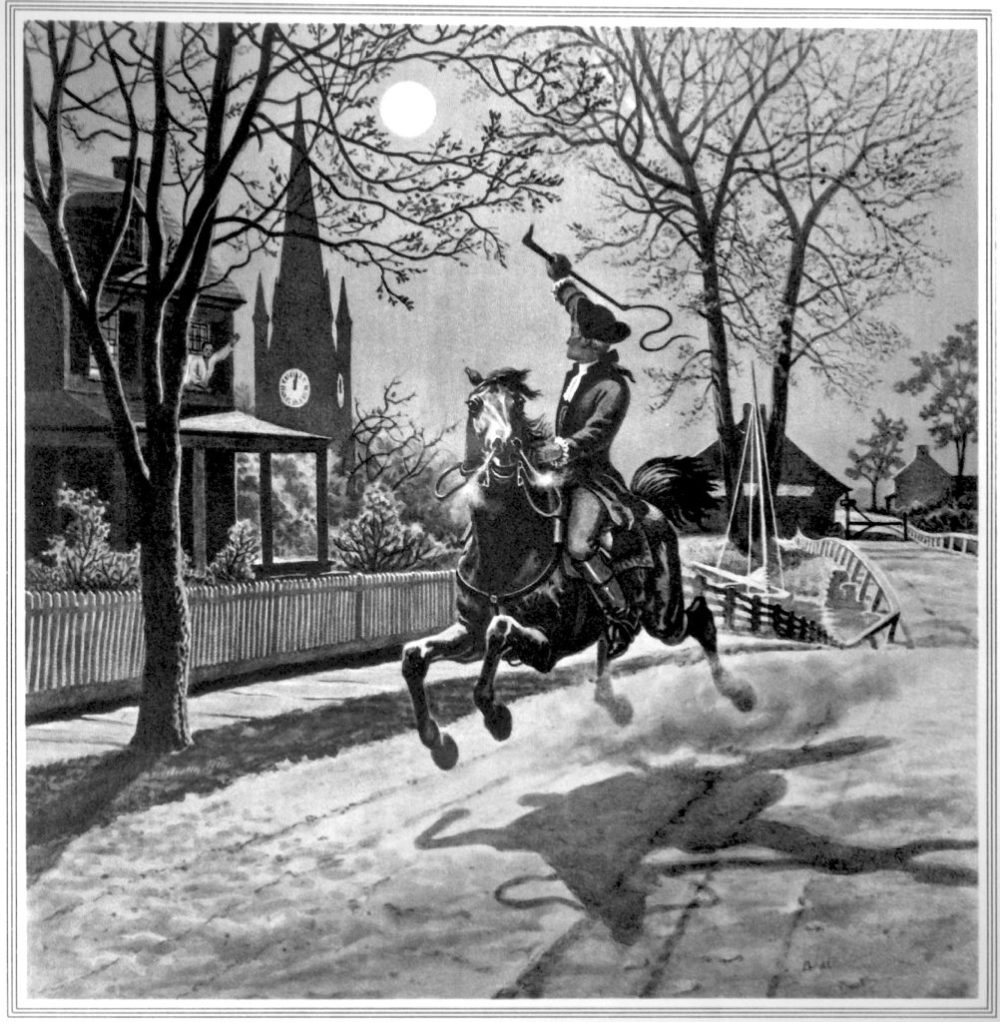

Like many turning points in history, the encounter at Lexington Green was not planned. British troops acting on the orders of General Thomas Gage were on their way to capture arms and munitions stored by the Massachusetts militia when they ran into Lexington’s “Minutemen” drawn up on the Green. Yet though both sides stumbled into the clash, Paul Revere’s warning that the British were coming seemed proof to the Americans that only by resistance could they preserve their liberty.

Since 1765, Britain had been flexing its muscles over the colonies, ending its age-old policy of “salutary neglect.” London had imposed duties – taxes, essentially – first on stamps, and then on paper, glass, and most gallingly, tea. All were designed to raise revenue to help pay off the costs of the French and Indian War, which had made Britain the dominant power in eastern North America.

Up to that fateful morning, Americans, whether in Massachusetts or Virginia, may have been proud subjects of King George III, but they also considered themselves free. For almost 170 years, since the first settlement at Jamestown, they had largely governed themselves through elected councils. That slavery had grown throughout the colonies, especially in the South, and that women did not have the same legal rights as men, reflected the realities of 18th-century norms, but did not negate the fundamental belief of colonial leaders that they had all the rights of Englishmen. It was with no hypocrisy in his mind that the Virginian Patrick Henry had uttered his immortal words less than a month before: “Give me Liberty or give me Death!”

In protesting against taxation without representation, the colonists set the stage for the fundamental American political philosophy, that all persons have natural rights that no arbitrary power can trample. It would take more than a year for Thomas Jefferson to encapsulate the American ethos in his eternal words that “all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

John Adams wrote late in life that only one-third of the colonists supported war against Britain. But even most Loyalists, who opposed both revolution and Independence, cherished their individual liberties. Long before July Fourth, Americans were marked by an unshakeable belief in freedom, derived equally from their religion, from Enlightenment thought, and from the experience of carving out a new society on a largely pristine continent.

The questions that would bedevil American history, foremost among them slavery, but also women’s rights and the rights of American Indians and later immigrant minorities like Asians, do not negate, but rather reaffirm the principles for which the Minutemen stood their ground on the early morning of April 19. In fighting for their own freedom, the colonists opened the door to remedying inequalities that later generations would consider incommensurate with the promises laid down in the Declaration of Independence.

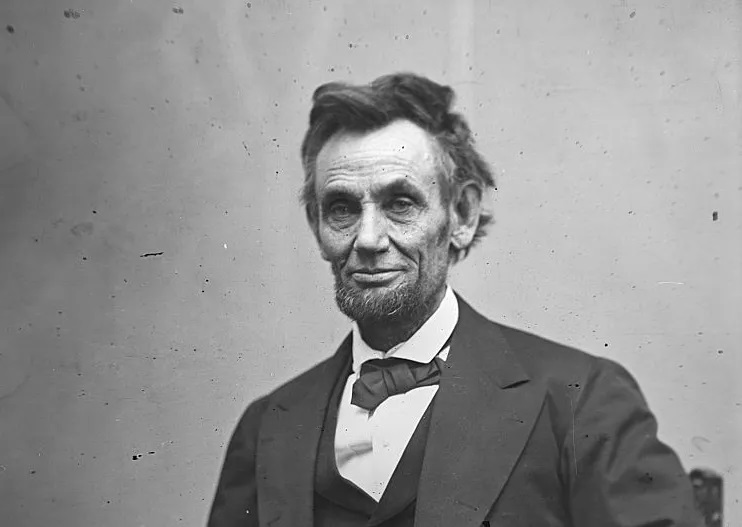

It was for that reason that Abraham Lincoln prized the Declaration above all else, and why he called it an “apple of gold” set within the silver frame of the Constitution.

America now embarks on eight years of commemorating the War for Independence, which ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. In a country badly divided by political partisanship, can the Declaration’s promise of equal rights, ensured by ordered freedom, serve again as the bonding agent for the most heterogenous society on earth, as it did 250 years ago? The need today is no less urgent than it was in 1775, but we have the wisdom of a quarter-millennium of success and failure to guide us through the woods.

Freedom is still the Revolutionary War’s legacy

Colonists fought for fundamental philosophy that all persons have natural rights

Paul Revere (1735 – 1818) rides to warn the people of Massachusetts that the British troops were advancing by boat, April 1775. (Getty)

When the first shot rang out at dawn on Lexington Green, a decade of frustration and growing alienation between the American colonies and the British government boiled over into armed conflict. By the time the British staggered back into Boston on the evening of April 19, 1775, having fought a running battle for twenty-five miles from Concord’s North Bridge and losing at least 73 killed, the American Revolution had begun. Like many turning points in history, the encounter at Lexington Green was not planned. British troops acting on the orders of General Thomas Gage were…

Leave a Reply