Two weeks ago, VJ day (Victory over Japan day) celebrated the end of the Pacific War. On August 15, 1945 Emperor Hirohito, with his high-pitched voice and arcane royal language, which was heard by his people for the first time, announced Japan’s surrender. Huddled around their radios the Japanese heard Hirohito say:

“We have ordered our government to communicate to the governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that our Empire accepts the provisions of their Joint Declaration [The Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945, signed by President Truman, Winston Churchill and Chiang Kai-shek, ordered Japan’s unconditional surrender or face ‘prompt and utter destruction’]… The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage… the Enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb [the atom bomb used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki]… should we continue to fight, it would result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but it would also lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

Thus, Hirohito’s curmudgeonly acceptance of defeat ended with the implication that Japan’s surrender was not only to save itself but also “selflessly” to save mankind. The emperor’s description of America’s “cruel bomb” also helped set up Japan’s post-war narrative of victimhood.

So, the Pacific war and indeed World War Two ended on August 15, 1945? Wrong. Heavy fighting continued until September 2 and incurred, in just three weeks, the deaths of an estimated 350,000 to 400,000 people, including tens of thousands of Japanese civilians who died of illness and starvation. In aggregate, this was about the same number of British people who died during five years of war in Europe.

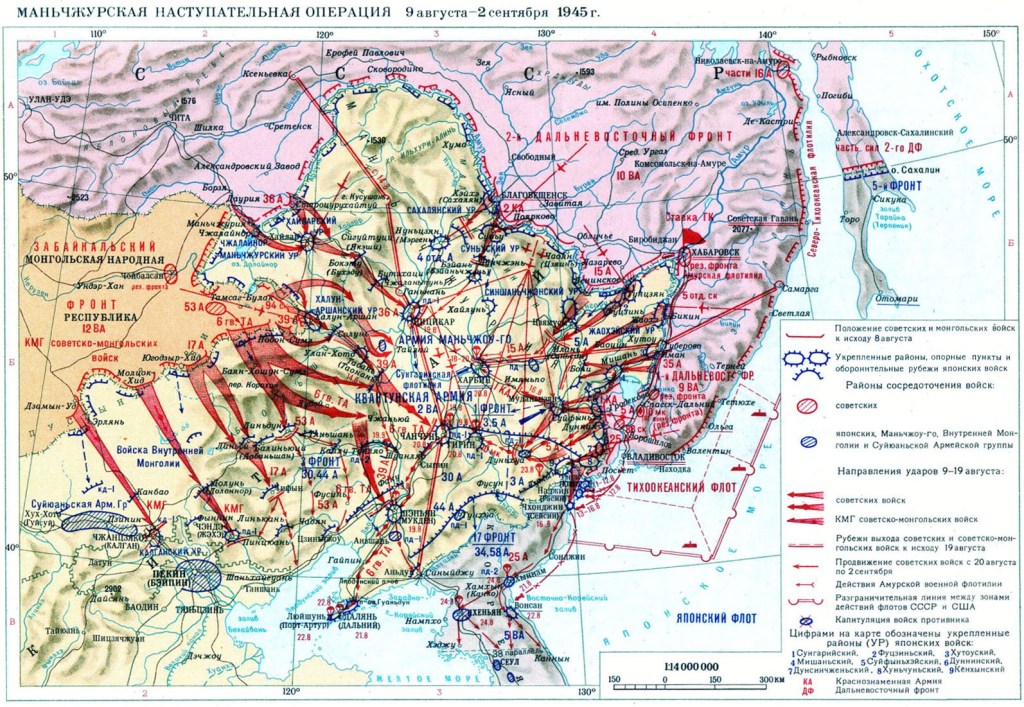

Reflecting the usual western-centric view of World War Two it is largely forgotten in the narrative of World War Two that our allies, the Soviet Union, continued to fight Japan after August 15, 1945 in areas as far afield as Mongolia, Siberia, Manchuria (Manchukuo), North Korea, the southern half of Sakhalin and the Kuril islands.

It may come as a surprise to some that allies who fought together to fight Hitler were not united against Japan. The Soviet Union remained determinedly neutral with regards to Japan until August 8, 1945. Although Japan and the Soviet Union, as well as its predecessor Imperial Russia, had been geopolitical rivals throughout the twentieth century, they came to an unlikely standoff agreement in 1941. After a five-month war fought along the disputed border between Mongolia and Manchuria, the warring nations signed the Japan-Soviet Neutrality Pact. It was an agreement for five years.

Their historic Asian rivalry would be put on hold as they both had other fish to fry; the Soviets were engaged in the Winter war with Finland and, under the auspices of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, annexing Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. Later, of course, Stalin had to concentrate on the little matter of dealing with Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s invasion of Russia in June 1941. Meanwhile, Japan needed to focus on a total war effort to subjugate China. For the next four years it suited both sides to stick to the neutrality pact.

As it finally dawned on some of Japan’s leaders in 1945 that their war with America and Great Britain was in danger of wreaking complete destruction on their country, Tokyo sought Stalin’s help to negotiate a face-saving surrender to the allies. The mooted offer was to leave the Chrysanthemum throne and the Japanese army intact while putting the prosecution of war crimes trials in Japanese hands. However, frustratingly for Ambassador Naotake Sato in Moscow, Japanese leaders in Tokyo, split between doves and hawks, could not provide him with clear instructions. Japan did though begin to negotiate an extension of the neutrality agreement with the Soviet Union that was due to end in April 1946.

But Stalin was stringing them along. Japan’s impending defeat by Britain and America was an opportunity he could not miss. A Soviet invasion of Manchuria, a prize possession of Japan’s empire, would provide ample revenge for Japan’s crushing defeat in 1905 of the Russian army at the Battle of Mukden and the sinking of virtually its entire fleet by Admiral Togo at the Battle of Tsushima. As Stalin noted in his VJ day speech, celebrated in Russia on September 2 not August 15:

“The defeat of the Russian troops in 1905 during the Russo-Japanese war left bitter memories in the minds of our people. It lay like a black stain on our country. Our people believed in and waited for the day when Japan would be defeated and the stain would be wiped out. We of the older generation waited for this day for forty years, and now this day has arrived.”

All the while, after the defeat of Nazi Germany, Stalin was planning to break the neutrality pact by a treacherous invasion of Japanese-controlled Manchuria, the Chinese province that they had ruled since 1931. Stalin’s planned intervention was made easier at the Yalta conference in Crimea in February 1945. President Roosevelt arrived with a clear agenda; the Soviet Union had to be brought into the war with Japan. Roosevelt did not want American troops to bear the burden of invading Japan alone. At this point it should be noted that the success of the Manhattan Project was considered far from certain.

Roosevelt may not have realized that by persuading the Soviets to invade Manchuria, he was pushing on an open door. Both Stalin and Roosevelt left Yalta happy. Stalin had agreement for his control of Eastern Europe while Roosevelt had Stalin’s promise to attack Japan. “This makes the trip worthwhile,” Roosevelt told his chief of staff, Admiral Leahy.

As the war in Europe ended in the summer of 1945, Stalin began to transfer troops and materiel eastwards. A blinkered leadership in Tokyo refused to believe reports from the frontline in Manchuria, where increasing Soviet patrols and exercises alarmed Japanese officers. A single Japanese spy alone counted 195 trains laden with 120 tanks, 2,800 trucks and 500 fighter planes heading for the Mongolian border with Manchuria. His report was ignored.

As Japanese officers later noted, reports of Soviet activity were “utterly inconsistent with the optimistic information received from high command.” Thus, when Japanese foreign minister Shigenori Togo was woken at 3 a.m. on August 9 to be informed of the Soviet surprise attack, he was completely astonished. It was a “Pearl Harbor” moment.

Although the Japanese army in Manchuria, which had been depleted of their best troops and equipment to shore up the defense of Japan, was able to put up a 700,000 strong army, its fighting effectiveness was rated at 35 percent at best. Against this force Stalin had massed 1.5 million troops around Manchuria’s borders under the command of Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky who had distinguished himself at the Battle of Moscow.

Japanese border defenses were quickly overrun. A withdrawn defensive line provided stiffer resistance. At the Battle of Mutanchiang some 60,000 Japanese troops held up 290,000 Russian troops for four days. The battle ended on August 17, two days after Emperor Hirohito’s surrender speech.

Elsewhere, Japanese defensive bunkers held out underground until August 26 before the Soviets brought in gas to finish off the holdouts. By then other Soviet forces had reached North Korea five days ahead of schedule. Meanwhile Japanese resistance on southern Sakhalin island, which was invaded on August 11, ended on August 25 when the capital city of Toyohara fell after fierce resistance. On August 18 Soviet amphibious forces landed on Shumshu island, the northernmost of the Kurils, the chain of fifty-six islands that stretch in a gentle curve from Hokkaido to the tip of the Kamchatka peninsula. The Kuril islands were quickly rolled up.

Fighting stopped on September 2. However, the Soviets occupied the lesser Kurils on September 3-5. These islands, adjacent to the northeast of Hokkaido, remain a sticking point in Japanese-Russian relations today. Although Japan renounced its claims to Sakhalin and the Kuril islands at the Treaty of San Francisco in 1951, it maintains that the lesser Kurils were not included. The result is that Japan and Russia are yet to sign a formal peace treaty — although a joint declaration in 1956 did acknowledge that the state of war had ended. Talks for the restitution of the lesser Kurils remained ongoing until last year. After Japan’s publicly declared support for Ukraine, President Putin withdrew from all negotiations.

The costs of the invasion were staggering. Some 12,000 Russian troops were killed while Japanese forces suffered 84,000 deaths. Of the 620,000 Japanese troops taken into captivity more than a third died. On top of that there was mass starvation and death wrought on Japan’s 2.6 million inhabitants in Manchuria.

The West’s ignorance of this bloody end to World War Two is par for the course as far as the historiography of the conflict goes. For many historians in Europe and America, the Pacific war was a sideshow to the main event — the war in Europe. In general coverage of the war, Asia occupies less than a third of most histories of the subject. Compared to the copious studies of World War Two in Europe, there are just a handful of histories of World War Two in Asia.

Yet the casus belli that brought America into the war, thus precipitating a world rather than another European war, were in China not Europe. America’s embargo of oil exports from Standard Oil of California to Japan because of the Roosevelt administration’s abhorrence of Hirohito’s occupation of China, precipitated the attack on Pearl Harbor and concurrent attack on Malaya, which was a stepping stone to the oil fields in the Dutch East Indies.

It was America’s policy of defending China that turned an Asian war into a world war. Thus, any objective narrative of the conflict should have it starting with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937, which heralded the start of Japan’s bid to conquer China, not the invasion of Poland in 1939.

Moreover, the scope of World War Two battlegrounds was significantly greater in Asia. Fighting there took place over 28 million square miles compared to 3 million square miles in Europe. The great naval battles of the war were fought in the Pacific, not Europe. The Battle of Leyte, the largest naval battle in history, spanned 100,000 square miles (more than the size of the United Kingdom) and involved over 1,000 ships.

By some estimates more people, combatants, and civilians, died in Asia than in Europe. An estimated 20 million people died in China alone, largely from starvation as well as the genocidal practices of the Japanese army. The infamous Rape of Nanking (250,000 dead) in 1937 was just a minor component of this slaughter.

As in Germany and Eastern Europe, Japan, under the leadership of Surgeon General Shiro Ishii, built a network of extermination camps in China; special medical equipment was imported from Germany via Bordeaux, using Japan’s uniquely outsized cargo submarines. Human experimentation comparable to that carried out at Auschwitz was done at Unit 731 in Harbin, Manchuria. In terms of casualties the Chinese holocaust was significantly greater than the Jewish holocaust.

Extensive war crimes were committed in every country that Japan touched. As for prisoners of war, some 30 percent of Allied POWs died in prison camps. Some did not get that far. In the Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia) Australian POWs were squeezed into bamboo pig baskets and dumped into harbors to drown. Meanwhile death rates of Indian POWs, by far the largest racial group captured by the Japanese army, were much higher at over 50 percent. Civilian suffering throughout Asia was extraordinary, particularly as Japan’s thin logistical supply lines meant that its armies had to live off the land. An estimated 60 million war refugees in Europe can be compared to 100 million war refugees in China alone.

The understanding of Asia and particularly China’s preoccupations today are impossible without an evaluation of its role in the second world war. As Oxford professor Rana Mitter, the leading expert on modern Chinese history, has noted in Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945:

“Contemporary China is thought of as the inheritor of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, or even of the humiliation incurred by the Opium Wars of the nineteenth century, but rarely as the product of the war against Japan.”

The misrepresentation of the date when World War Two ended may seem a minor point of correction. But it speaks to the wider issue of the West’s minimization of the Asian component of World War Two. Now more than seventy-eight years later, is it not about time that British and American historians, who have dominated the historiography, start to revise their western-centric narrative and change the date of the end of World War Two?

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.