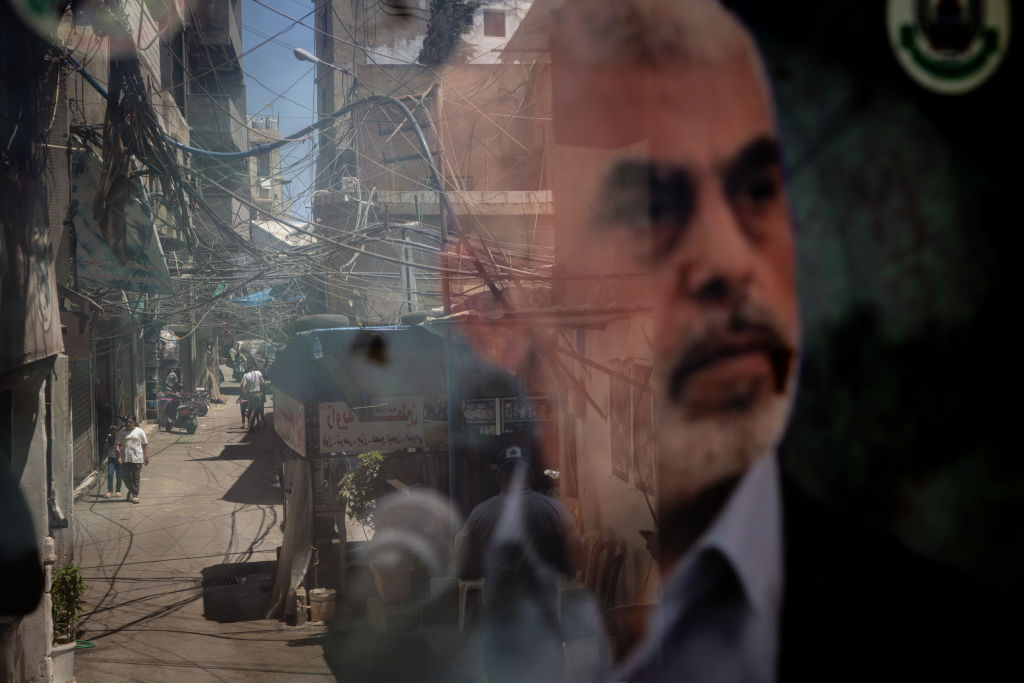

Yahya Sinwar, the Hamas leader and strategist responsible for the largest massacre of Jews since the Holocaust, is dead, killed by the Israeli Defense Forces in a tunnel beneath his hometown of Rafah in Gaza.

Although the Biden administration (rightfully) congratulated Israel, both President Biden and Vice President Harris had previously demanded Israel not stage a major military operation in Rafah, where Sinwar and other Hamas leaders were killed. That advice matched the administration’s strategic wisdom throughout the conflict.

With Sinwar gone, the key questions now are: what is the endgame in Gaza? And how does Israel’s success in Gaza affect the current battle against Hezbollah in Lebanon and the future battle against the Islamic Republic of Iran?

Answering those questions requires some background on Israel’s strategy and the foes they are fighting.

For months, the Biden administration and most Western countries have demanded a ceasefire in Gaza. Israel has always rejected that demand, even if it included the release of the roughly 101 remaining hostages. Hamas, too, rejected ceasefire proposals unless Israel made major concessions, which it refused to make.

Why is a ceasefire a bad idea, according to Israel’s government and most of its population? Because they believe it would allow Hamas to rebuild its terror army, continue its tyrannical rule over the Gaza Strip and block anyone else from governing. Once they rebuilt, there would be no guarantee they wouldn’t launch another deadly attack.

Remember, Hamas had a ceasefire with Israel until October 7, 2023, when Sinwar and his terrorist army struck, killed, raped and kidnapped innocent civilians. Gaza was not occupied at the time and had not been occupied for years. It was wholly controlled by Hamas, which allowed residents to cross the border and work in Israel. It was a “cold peace.” The Iranian proxy group chose to break it by launching an unprovoked, lethal attack on Israeli civilians.

In the aftermath of that attack, Israel had no choice but to strike back. The main aim was not revenge or even recovering the hostages. It was more ambitious than establishing deterrence. Israel’s fundamental decision was that Hamas, committed to killing Jews and destroying Israel, had to be destroyed. It could not be allowed to rebuild or govern Gaza.

The capstone of that effort is the elimination of Yahya Sinwar, who planned the October 7 attack. Nearly all other Hamas leaders had been killed before him. Nearly all their weapons stores and most of their tunnel structure had been destroyed.

That does not end the fighting unless Hamas’s surviving leaders (or perhaps isolated groups) accept Benjamin Netanyahu’s latest offer: give up the hostages and we will let you live. Israel has already shown what will happen if they refuse.

Still, their leaders may be willing to fight to the death, perhaps led by Sinwar’s surviving brother, himself a terrorist leader.

Whatever Hamas decides now, they have lost control of the vital border crossing to Egypt, the Philadelphi Corridor. Hamas used tunnels under that corridor to bring in weapons and advisors from Iran. Israel has taken that area, bordering Rafah, and has no intention of relinquishing it, no matter what Western nations demand or Egypt publicly proclaims.

Israel’s problem in Gaza now is less finishing the military operations in the area and more figuring out how to govern, or at least pacify, that truculent, Jew-hating territory. No Arab state wants any part of it and never has. The UN is not capable of governing it and is untrustworthy, in any case. They failed to police the UN resolution that established southern Lebanon as a demilitarized zone. UN forces let Hezbollah reoccupy that neutral zone on Israel’s northern border and dig military tunnels next to UN outposts.

In its fight against Israel, Sinwar and Hamas had powerful allies, all of them Iranian proxies. It is those proxies and their state sponsor that preoccupy the Jewish state now.

The head of the snake is Iran. Its support not only meant weapons, cash and technical support for the terrorists in Gaza, it meant activating another proxy, Hezbollah, in southern Lebanon, to divide Israel’s defense. Hezbollah was far better armed than Hamas and helped govern Lebanon as an equal partner of the “official” government. It effectively controls southern Lebanon and the southern suburbs of Beirut and has turned them into armed camps beneath civilian structures.

The day after Hamas struck Israel, Hezbollah launched its own strikes. At Iran’s direction, it begin firing thousands of missiles and lethal drones into Israel. That onslaught has continued until now. It will stop only when Israel takes out Hezbollah’s vast stores of weapons.

Hezbollah’s attacks on Israel had two major effects. First, they forced over 60,000 residents to flee their home in northern Israel and remain displaced until now; and second, they forced Israel’s military to divert resources from Gaza to deal with Hezbollah

Iran did more than activate its Lebanese proxy. It supported another proxy, the Houthis in Yemen, in their missile attacks on Israel and international shipping.

Finally, Iran decided to attack Israel directly, firing a massive missile and drone barrage at Israel from its own territory, first in April and then in October.

The US, Israel’s only real ally, responded in two contradictory ways. They supplied Israel with ammunition and defensive (anti-missile) systems, but urged restraint against Iran after the April barrage. The Israelis complied with a soft, symbolic strike. It was more mistaken advice from Washington. It merely convinced Iran that Israel was weak, overwhelmed with multiple adversaries and unable to confront its gravest threat. Israel’s feeble response did nothing to deter Iran from striking again, which they did in even great force on October 1.

For Israel, the strategic problems posed by Iran and its proxies are the most complex facing any nation on earth. Why? For two reasons. First, they come from multiple directions, all at once. Second, meeting them requires dramatically different kinds of military organizations and strategies. Striking terrorists embedded among civilians in Gaza or the West Bank requires on-the-ground counter-terrorist forces, capable of fighting hand-to-hand and building-to-building. Dealing with Iran is completely different. It is a peer competition, over 2,000 miles away, equipped with long-range missiles and deeply-buried military facilities. Hezbollah’s capabilities fall somewhere between Iran’s and Hamas’s.

Israel’s basic decision, after the Hamas attack on October 7, was to fight its enemies sequentially, if possible. That’s a standard military strategy. Germany did it in both World War One and Two. Thinking they had enemies on both their east and west, they chose to hit France first and try to postpone a full-scale war with Russia (the Soviet Union) until France was defeated. That worked in 1940 but not in 1914. In World War Two, the United States approached its enemies in the Atlantic and Pacific the same way. Well before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt met with Winston Churchill and agreed the US would make the war in Europe its top priority. It would merely try to hold off the Japanese until the war in Europe was finished. As it happened, the US proved strong enough to fight a full-scale war in both theaters, even while devoting more resources to Europe. The US Navy’s unexpected victory at Midway, which decimated the Japanese carrier fleet, meant it could defeat Japan even as it was devoting more resources to defeating Nazi Germany.

Israel is following the same path, approaching its enemies sequentially. The war against Hamas is not entirely finished, but it is nearing the end. The one against Hezbollah will continue a little longer, until Israel has decimated the weapons stores in Lebanon. The military goal is to strike Iran without fearing a major missile and drone attack from the north.

The strike against Iran is likely to come when the job in Lebanon is finished, even if there is no long-term guarantee against Hezbollah returning. Israel has selected its initial Iranian targets and taken out most of the enemy radar in Syria and Iraq, the path Israeli jets are likely to take when they attack Iran.

The Israelis have also deepened their tactical coordination with the US. The good news for Jerusalem is that Washington has sent naval forces to the region and supplied Israel with a high-altitude missile interception system, known as THAD, plus a hundred or so US soldiers to man it. Those transfers give Israel crucial defensive assets, send a message to Iran, and pose a danger for Tehran if their attacks kill Americans.

The bad news for Jerusalem is more than the sharp constraints the Biden administration has put on Israeli targets in Iran. It is also the unconscionable action of leaking highly secret targeting information to the Washington Post, as soon as the Israelis shared it with the White House. That leak tells Iran where to concentrate their defensive efforts and where not to bother. The words that best describe that leak cannot be uttered in polite company.

How seriously will Israel take Washington’s advice on what to strike? Very seriously, even though Israel will ultimately decide what’s best for its own security. In making those decisions, though, it has good reasons to listen closely to Washington. The US is Israel’s only real backer and a major source of vital military aid.

If Israel does accept Biden’s constraints and avoids hitting Iran’s deeply buried nuclear facilities or its vulnerable oil infrastructure (averting a gas-price spike before the US election), those promises are likely to apply only to Israel’s first strike. If Iran hits back hard, then all targets will likely be on the table for Israel.

When Israel does strike, it will begin with a cyberattack and comprehensive campaign to take out all air defense radar systems in Iran and its neighbors. Once that is done, the IDF will focus its initial kinetic attack on Iran’s military installations and leadership of the regime and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Israel will try its best to distinguish between regime targets and the civilian population, both for ethical reasons (they never target civilians and try to avoid collateral damage) and political ones (they want to weaken the regime and fear that hitting civilians could strengthen it).

Once Iran’s radar is taken out and Israel has air dominance, it will certainly go after military installations. The 64,000 Shekel question is: what else beyond that?

It is still unclear if it will attack oil installations, starting with Karg Island, refineries and perhaps ports. Oil is the regime’s only real source of foreign currency. It should have been neutralized by sanctions, as it was under Trump, but the Biden administration had a different idea (essentially appeasement in hopes of cooperation). That failed abysmally and allowed Iran to refill its coffers, fund the Revolutionary Guard and its proxies across the region and pay off some domestic actors to retain their political support.

If Iran strikes back in force, which seems likely, then Israel must decide whether to take on the nuclear installations. A deliverable nuclear weapon from Iran could wipe the Jewish state off the map. But taking out Iran’s nuclear facilities is extremely difficult and taking them out without American support is even harder.

On the other side of the ledger, the threat is great, the timing is growing short before Iran has nuclear bombs, and Israel will never have a better chance to destroy that program. If Israel’s government decides that striking those facilities would be in their national interest and if it thinks it has a decent chance of success, it will go forward, no matter what the Biden administration says.

Israel might go after the nuclear sites as part of the earlier strikes, if they cannot disrupt them with cyber. The uncertainty that creates for Iran is a big plus for Israel. That’s why telegraphing Israel’s targets — taking those sites off the table — was such a blunder by the Biden administration.

If it all sounds uncertain and dangerous, that’s because it is. The stakes are as high as any since the end of the Cold War. They include Israel’s safety, the survival of the Islamic Republic, the stability of the world economy, and the United States, Europe, and Russia, which don’t want to be pulled into a major war in the Middle East.

Leave a Reply