Like millions around the world, I have spent recent days watching — sometimes forcing myself to watch — these images coming out of Afghanistan, as the nation has fallen to the triumphant warriors of the Taliban with their untamed beards and M4 rifles.

They are the kind of images that come along once in a generation, but remain seared in the collective memory for decades. Many have compared these scenes of American defeat to the famous choppers-on-the-US-Embassy images of Saigon on April 30, 1975. And there are obvious, uncanny echoes.

For me, however, the better comparison is with the fall of Phnom Penh (which happened just two weeks before the collapse of Saigon), when the rural Maoists of the Khmer Rouge marched into the Cambodian capital, ready to inflict their atavistic communism on a roiled and helpless country.

A few brave photographers lingered in Phnom Penh that first appalling day, and what they captured, above all, was the growing, bewildered terror of many Phnom Penh citizens (and trapped westerners). And that is exactly what we are seeing in Kabul: the Afghan parents so desperate to save their children they hoist a baby into the arms of an unknown soldier. Or the crush of Afghan and western escapees at the airport perimeter, broiling in the sun, and slain by Isis bombers, or by simple dehydration.

Above all, I have been hypnotized by one extraordinary sequence: the young men who desperately jumped on the wheels of that speeding C17 cargo plane, and then, inevitably, fell to their deaths moments later, as it ascended. And the reason these particular images strike me is that I cannot easily explain them.

That is to say: I can certainly see why you would flee to an airport from an advancing army. I can also see why you might, in extremis, hand your baby to a potential savior, however anonymous. But I do not, at first glance, understand the men jumping on the fuselage of an accelerating cargo jet.

It is a basic question of odds. If you leap on to the landing gear of a plane heading for the skies, you are virtually certain to die soon after. So why do it? Why not just turn around, and grab your chances? Why not, in fact, take up a gun, a sword, a spade, and fight the Taliban? You might have only a 10 percent chance of making it through, but at least that’s a real chance. And if you die, you die with pride: defending your honor, your country, your women.

So, why did Afghans cling to planes? One reason might be the howling terror induced by the Taliban. They are notoriously cruel, and they use this as a tactic to make larger, better-armed opponents flee or surrender. Isis did exactly this in Iraq and Syria. And yet even Isis in Syria did not invoke the bizarre behavior seen in Kabul airport.

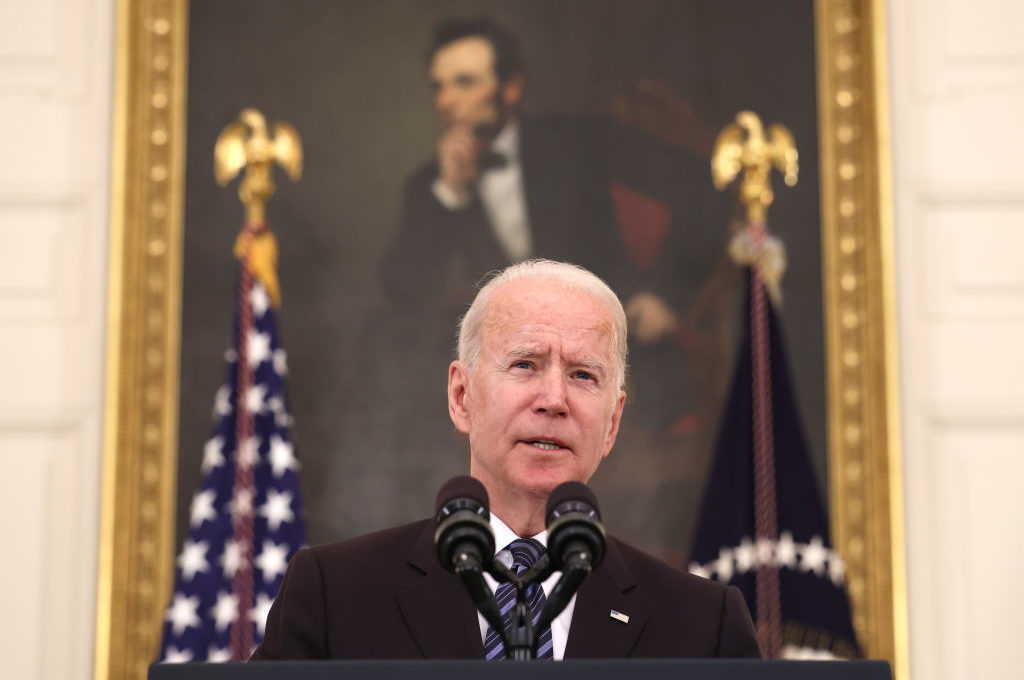

An alternative explanation is that Afghan men — and it was 100 percent men jumping on the landing gear of that plane — lack the fortitude to fight (as President Biden, rather shamefully, has implied). Yet this is belied by history: Afghan is the ‘graveyard of empires’ — it is known for its militaristic spirit. And 70,000 Afghan soldiers have already died fighting the Taliban, so the idea that they have suddenly all become cowards doesn’t work.

Instead, I think the answer is God.

The origins of the Taliban are explicitly religious. When they were founded in 1994, by the one-eyed cleric Mullah Omar (with much assistance from Pakistani intel: the ISI), they took on a name, Taliban, which evokes holiness, as it derives from the Pashto word meaning ‘students’ — i.e. students of the faith, holy scholars. Ever since, the Taliban have styled themselves as an Army of God. They march with the Koran and they pray between skirmishes. They are akin to Christian crusaders, only with looted American night-goggles.

Therefore, in fighting the Taliban, you are not just fighting an enemy, you are fighting Allah. And for highly religious Afghans (and Afghans are some of the most religious people on earth), this must create enormous psychic dissonance.

For a start, you are likely to lose to the Taliban: because Allah, in the end, always wins. As an old Afghan proverb, rehashed by the Taliban, presciently says: ‘you have the watches, we have the time’. To make it worse — for a conflicted Afghan — by fighting Allah, even in the perverted form of the Taliban, you are possibly sending yourself to Hell. Therefore, even if you loathe and fear the Taliban, you should not fight them.

And so, gripped in this gruesome psychological trap, you are guided towards the only other option: you run away from them, even if that ‘escape’ means near-certain death, as you plunge to the earth from a C17 cargo plane.

That, perhaps, explains the horrible mystery of the doomed Kabul stowaways. I also think it has a wider and more ominous lesson for the west, especially America.

The US had so many advantages in Afghanistan: more money, better guns, faster missiles, all the tech you could want. But the Taliban had absolute cultural self-confidence (just like the Khmer Rouge in 1975), and America does not have this innate self-confidence, not any more. Not in Asia, not at home.

This really matters, because around the world we face rising enemies with the Taliban’s level of self-regard. The Russians have a nationalist spirit untroubled by futile, divisive culture wars. The Chinese firmly believe they are the Middle Kingdom, destined to rule the world as they did before. Islamists everywhere think Allah is on their side and we are doomed materialists, and the fall of Kabul will only encourage them.

What can we do? We need to find the muscle memory of Western greatness. For all the flaws of the West, no civilization on earth has delivered, to its citizens, so much freedom, so much prosperity, so much human happiness. Until we rediscover this true faith in ourselves, we will flee in fear before those with a cruder yet stronger creed, like the terrified citizens of Phnom Penh and Kabul.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.