The EU is building a wall — and they’re going to make Belarus pay for it. This week, the tiny Baltic nation of Lithuania began erecting a barbed-wire border fence on its frontier with its neighbor, Europe’s most notorious autocracy. Meanwhile, Brussels is ramping up economic sanctions against Belarus.

Lithuania’s parliament has declared a state of emergency, citing a sharp rise in migrants attempting to illegally cross the border. More than 800 made the journey in the first week of July alone, coming from countries like Iraq, Iran, Syria and the Congo. In response, hundreds of troops have been deployed and construction of a 340-mile barrier is underway. The EU’s newly established border agency, Frontex, has also agreed to step in to deal with the ‘urgent and exceptional pressure’, dispatching its own officers and patrol cars.

It seems Brussels’s former refugee policy is now ancient history. In 2015, member states were divided by Hungary’s decision to erect an electrified fence on its border with Serbia and Croatia. Budapest pitched the initiative in response to thousands of migrants fleeing conflicts in the Middle East, describing it as essential for the ‘defense of Europe’. Thousands turned out to protest against the move, insisting that refugees were welcome in the bloc. Those voices now appear to have lost the argument. The acute European migrant crisis of 2015 has passed, but cracking down on illegal migration is now an accepted part of European politics.

Officials in Vilnius accuse the Belarusian government of shipping desperate people across the border as part of a deliberate policy. Belarus, they argue, is trying to destabilize the bloc. While a more muscular border policy is broadly accepted in Europe, it still has the potential to cause ruptures. Speaking at a meeting in Brussels, Lithuanian minister for foreign affairs warned that Minsk is using refugees as a ‘hybrid weapon’ and called for fresh sanctions against its government.

The country’s officials have struggled to cope with a 20-fold increase in migrants since last year. A number of those claiming asylum are complaining of poor conditions, with hundreds packed into a converted school. One young Afghan told the Associated Press that he had handed over $1,400 for a flight to Minsk after ‘a friend pointed out this new way to Europe’. Others say they were offered buses to the border upon landing.

Minsk’s airport was the setting for a major international incident just a month ago — a likely cause of Belarus’s newfound ‘humanitarianism’. Authorities ordered a Ryanair plane in Belarusian airspace to land, detaining the editor of an opposition-backing media site and his Russian girlfriend. The move sparked outrage and fresh sanctions from the EU, with one commissioner describing it as ‘state-sponsored piracy’.

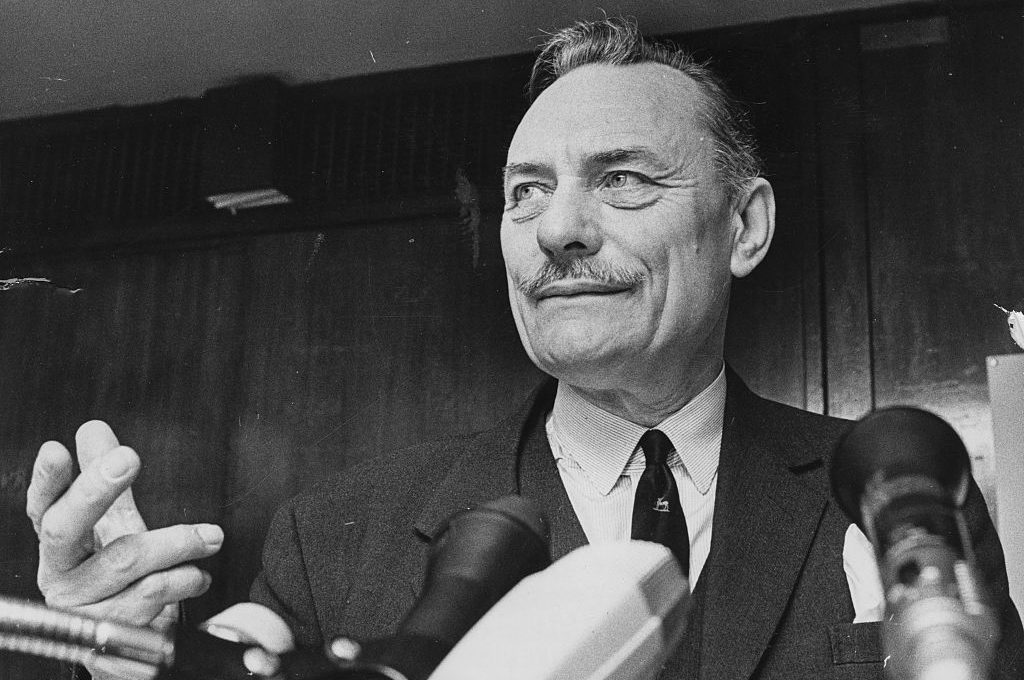

The journalist, Roman Protasevich, stands accused of organizing the colossal street protests that rocked Belarus in the wake of last summer’s presidential election. The opposition, and most international observers, say the poll was rigged in favor of authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko, who has held the country’s top job since the fall of Soviet Union. Tens of thousands took to the streets to demand a fresh vote. They were met with a violent police crackdown while the Lukashenko flatly refused to step down.

Brussels explicitly supported the protest movement and championed its leaders, such as former presidential candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, who has since fled to the EU. Lithuania has, in fact, played host to almost all of the exiled opposition, including both Tikhanovskaya and Protasevich, as well as leading the charge in Brussels for harsher sanctions.

However, despite its explicit support for the opposition, the bloc has found itself effectively unable to influence the situation in the Eastern European nation. In the past, Lukashenko had cultivated a relationship with Brussels, playing its officials off against those in Moscow for favorable economic deals in exchange for influence. Sanctions, however, have effectively killed any leverage the EU might have had over Minsk and, far from dislodging Lukashenko, have driven him to seek unequivocal financial and political support from Russia.

The latest row is an uncomfortable one for Brussels. While Lithuania has welcomed Belarusian political activists with open arms, they appear unwilling to accept the steady stream of African and Middle Eastern migrants crossing over from the country.

Just two years ago, Europe celebrated three decades since the fall of the Iron Curtain. Now, the EU is dividing the continent once again. If that really was Belarus’s plan, it’s working.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.