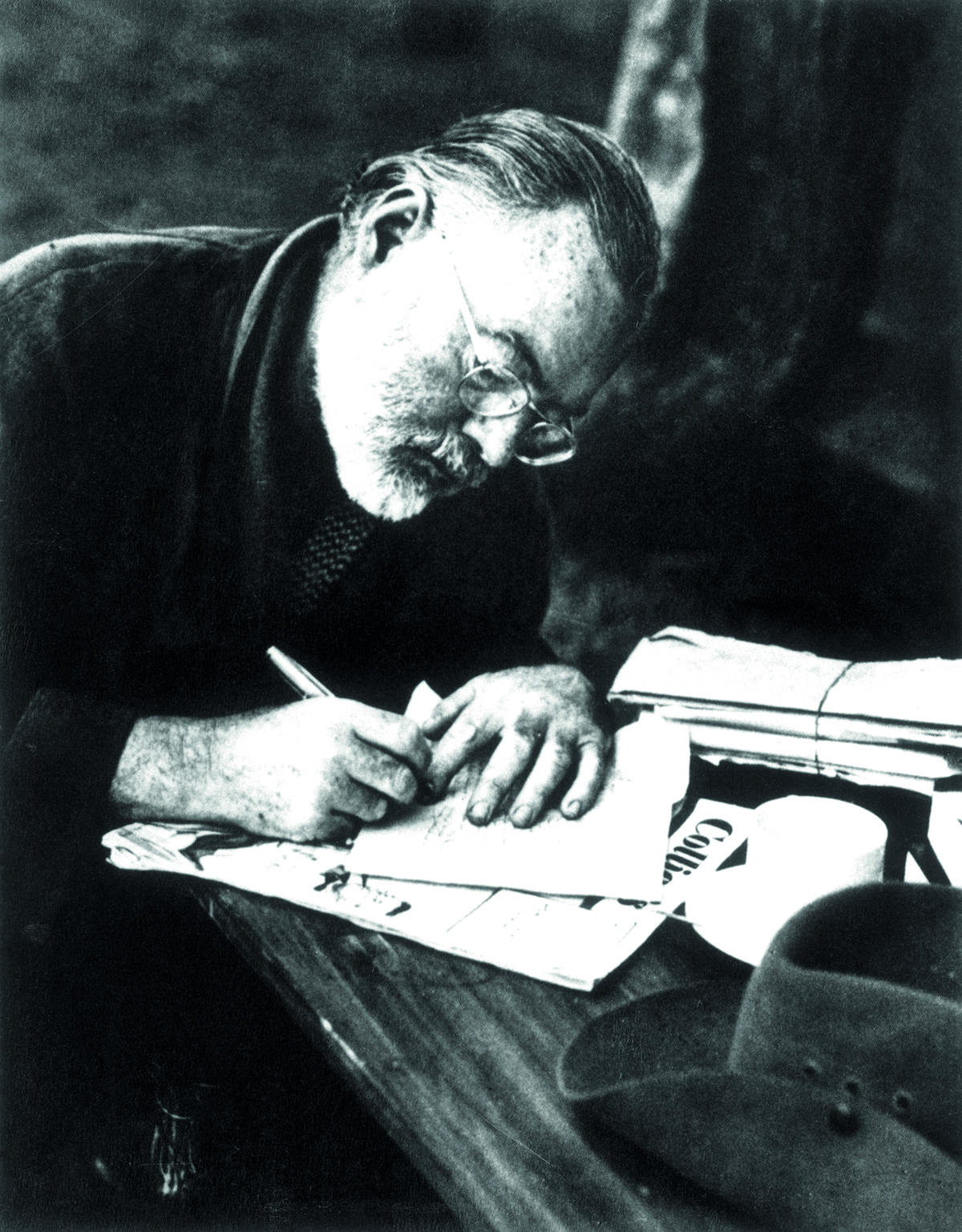

It was July 2, 1961. Ernest Hemingway was three weeks shy of his sixty-second birthday. He had been living comfortably in a cabin in Ketchum, Idaho, with his fourth wife, Mary. He liked it there. He liked the hunting and fishing and the clean air. Still he had a plan.

That morning he padded to the basement in his pajamas and bathrobe. He unlocked the gun closet. He selected a favorite shotgun, a double-barreled twelve-gauge. He put a shell in each barrel. He put the muzzle of the gun in his mouth.

Why pull the trigger now, after so many years of defying death?

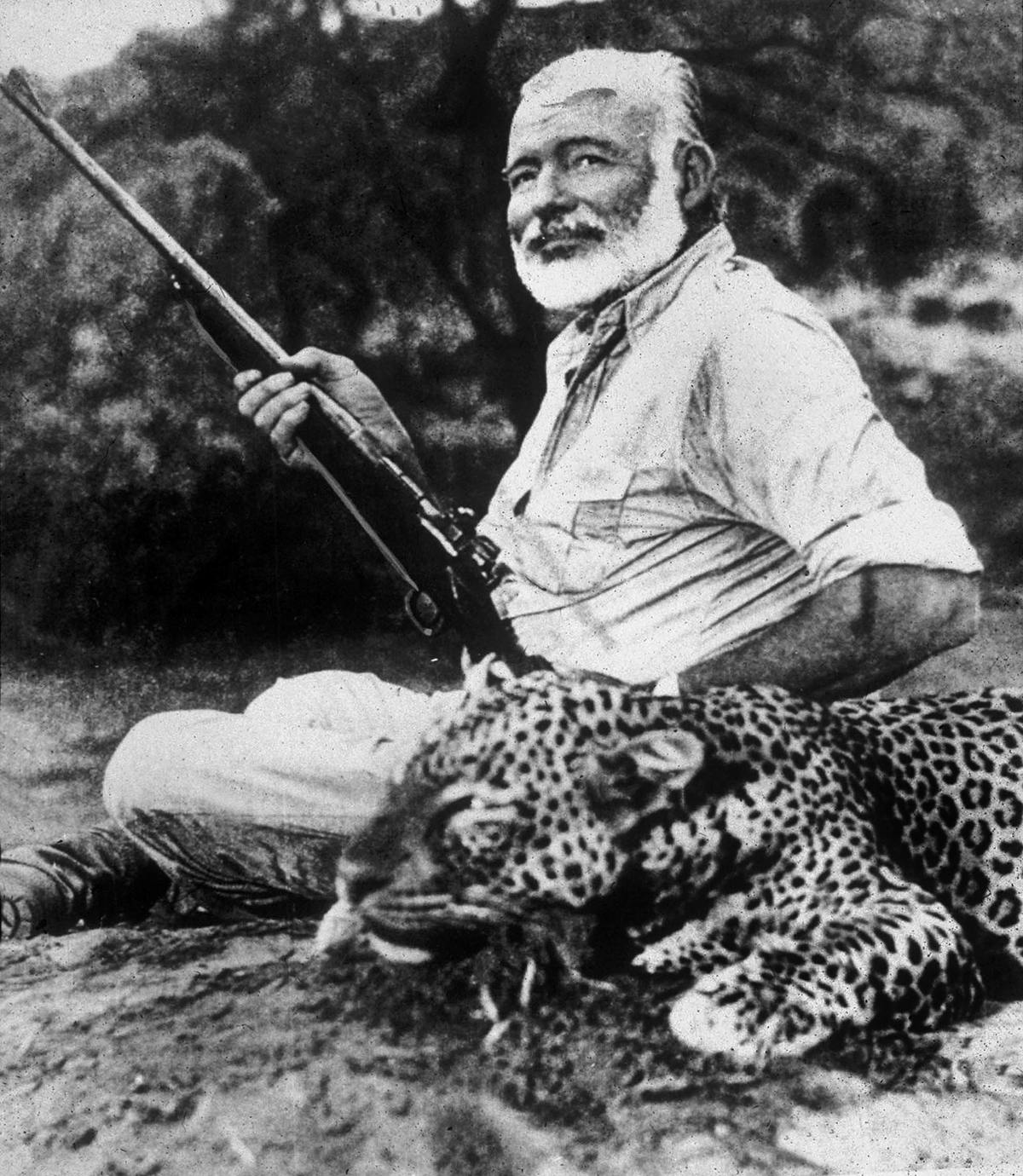

Eight months earlier he had checked into the Mayo Clinic as “George Saviers,” the name of his elderly doctor in Ketchum. The sixty-one-year-old Hemingway was thinner and frailer than the barrel-chested celebrity the world knew. Doctors diagnosed a mild case of diabetes and an enlarged liver. He was “depressive,” they said, and “potentially suicidal.” As the famed big-game hunter once told Ava Gardner, “I spend a hell of a lot of time killing animals so I won’t kill myself.”

He endured more than a dozen electroshock treatments at Mayo. After that, he claimed he felt better. “People reported seeing him on his hikes,” one psychiatrist noted. “He answered their greetings with smiles and nods.” But he felt his vocabulary shrinking. His memory was full of holes.

His suicide has been seen as one of literary history’s mysteries. Biographers blamed it on his prodigious drinking, a hereditary blood condition, even a so-called “Hemingway curse” that led his father and two of his five siblings to take their own lives. But while many factors may have contributed, I am convinced that they miss the main point. I think Hemingway pulled the trigger for the same reason my friend Junior Seau, an NFL football star of the 1990s and early 2000s, killed himself in 2012: he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the now-famous brain disease that strikes down boxers, football players and other athletes. A literal bruising of brain tissue, CTE affects memory and warps personality. In the end it robs you of your self.

There is plenty of evidence that Hemingway could have had CTE. At sixteen, he was knocking heads as a leather-helmeted lineman for the Oak Park High School football team in Illinois. He wrote an English-class report about hard-hitting football.

Two years later, during World War One, he was an eighteen-year-old ambulance driver in France. A mortar shell exploded a few yards away, killing two soldiers who were standing nearby. Hemingway was blown off his feet, knocked unconscious with wounds to his legs and his head.

In 1928, after a boozy night with Archibald MacLeish, Hemingway took a bathroom break. Reaching for the chain that flushed the toilet in his Paris apartment, he accidentally tugged the cord that operated a skylight. The skylight crashed down onto his head, leaving him with what one report calls “a traumatic head injury” as well as the horseshoe-shaped scar on his forehead that he carried for the rest of his life.

During World War Two, photographer Robert Capa threw a London party in Hemingway’s honor. Refreshments included ten bottles of scotch, eight bottles of gin, a case of Champagne and a magnum of brandy. When the liquor ran out, they designated a driver who was “no drunker than Hemingway.” The driver crashed into a water tank, sending Hemingway into the windshield headfirst, hard enough to crack the windshield. He survived with a concussion and a head wound that took fifty-seven stitches. After that he reported double vision, memory lapses and headaches that came “in flashes like battery fire.”

“And that’s hardly the whole story,” says Dr. Andrew Farah, a forensic psychiatrist who has studied Hemingway’s many head traumas. In France, not long after D-Day, Hemingway was riding in the sidecar of a motorcycle when an anti-tank round sent him flying. He hit his head on a boulder. According to Farah, who wrote a little-noticed 2017 book called Hemingway’s Brain, “That was one of nine or ten major concussions we know of. There were many more subconcussive hits to his head, and we’ve now learned that multiple subconcussive blows can have the same effect as concussions.”

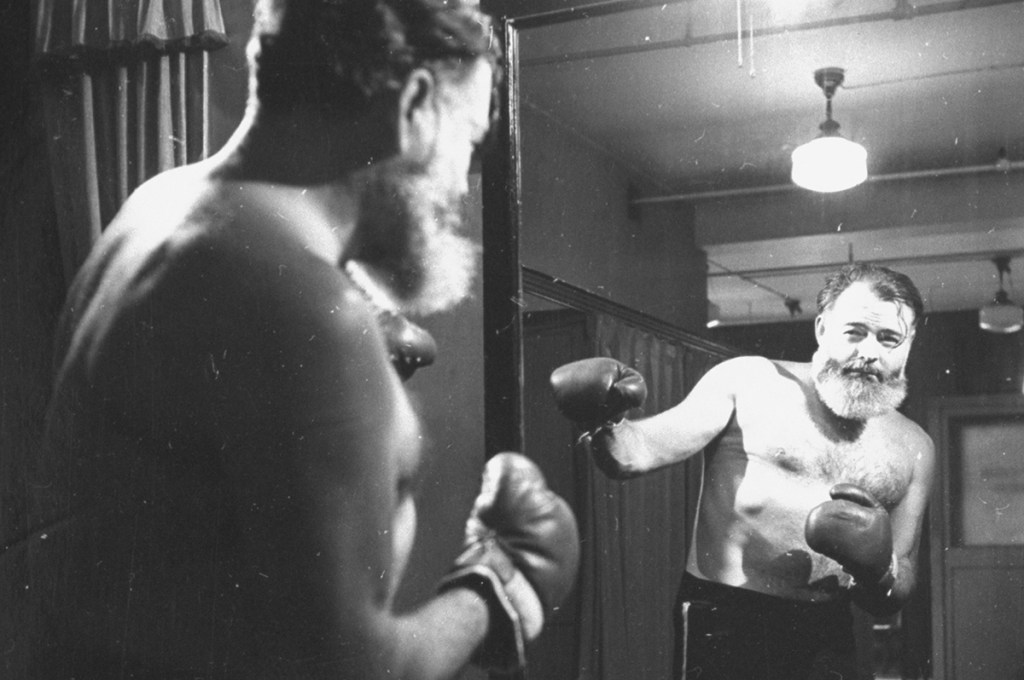

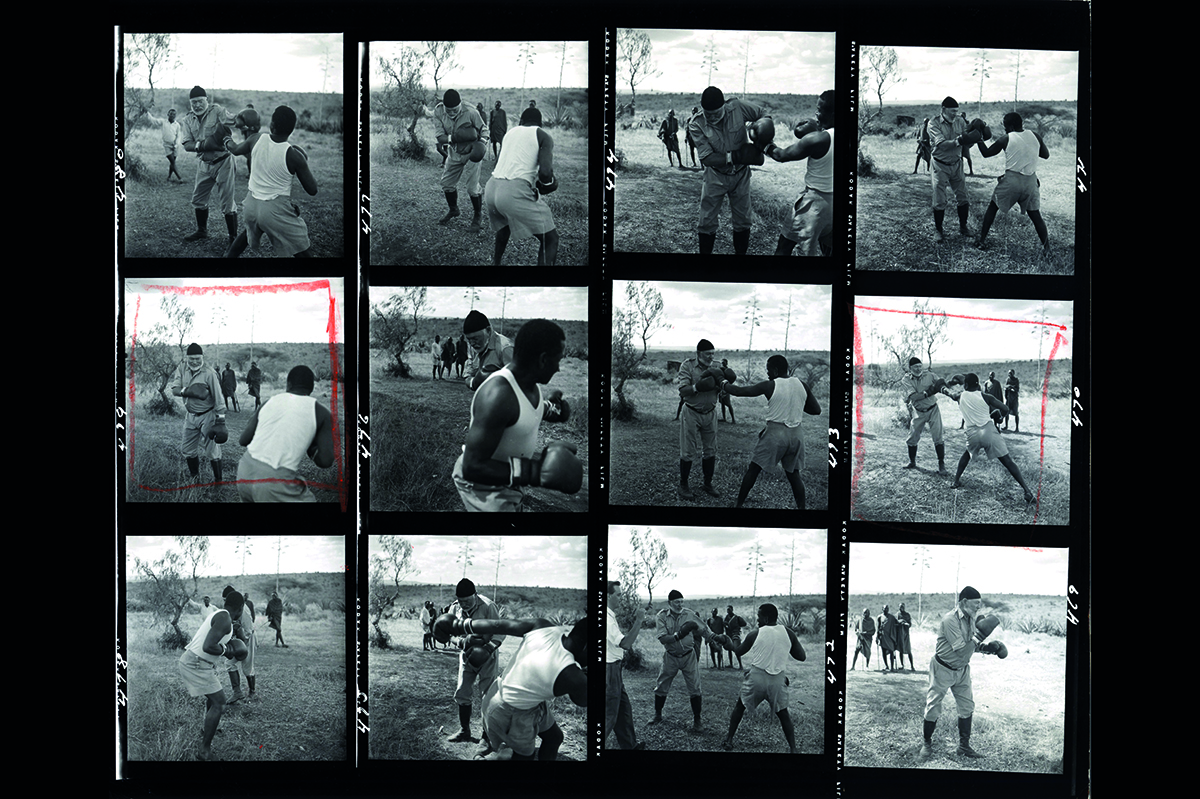

Hemingway’s boxing exploits are legend. “My writing is nothing, my boxing is everything,” he claimed. In a 1929 match — with F. Scott Fitzgerald serving as timekeeper — he was decked by a punch to the temple. Another bout went unnoticed for years: while working on a baseball book called Electric October, I ran across an account of Hemingway going skeet shooting with several Brooklyn Dodgers in 1942. The Dodgers held spring training in Havana in those days. That evening he invited some of them to his house for drinks. Everyone was soused by the time the host challenged Hugh Casey, a notoriously ornery 6’1″, 210-pound pitcher, to a boxing match. Casey was lacing up his gloves when Hemingway sucker punched him. The burly pitcher tumbled into a tray full of liquor bottles. Then he stood up. As one Dodger recalled, “Without saying a word, Casey started hitting him. Really belting him… Casey belted him across some furniture, and there was another crash as Hemingway took a lamp and table down with him… Hemingway was getting angry. He’d no sooner get up than Hugh would knock him down again. Finally he… made a feint with his left hand and kicked Casey in the balls.”

In 1949, Hemingway slipped on the deck of his fishing boat. “He hit his head and busted it down to the skull,” says Farah. Doctors told him that only the thickness of his skull had saved his life. Hemingway liked that. “Two surgeons,” he wrote, “said that I have a very thick skull. This may be literary criticism.”

Five years later he was on an African safari with Mary, flying in a single-engine Cessna. Their pilot swerved to avoid a flock of ibises, struck telegraph wires and crash-landed between beside what the New York Times called “a sandpit where six crocodiles lay basking in the sun.” Pilot and passengers spent the night in the jungle, hearing elephants stamping through the brush.

The next day they boarded another plane, which caught fire and crashed. With smoke filling the cockpit and the door jammed, “Hemingway was too big to get out the window,” says Farah. “So he chooses very unwisely to bust open the door with his head, giving himself a skull fracture and another concussion.” News reports had him emerging from the jungle “swathed in bandages… carrying a bunch of bananas and a bottle of gin.” According to United Press International “the novelist, who is fifty-five years old, quipped, ‘My luck, she is running very good.’”

That fiery second plane crash spurred reports that he was dead. Hemingway enjoyed reading those stories so much that Mary once told him, “Turn off the light, go to bed, you can’t read your obituaries all night.”

By the mid-1950s, says Farah, “his cognition was not the same. His memory was getting worse. His headaches were persistent.”

CTE would not be named for decades, but the author was familiar with “punch-drunk syndrome” or dementia pugilistica. In “The Battler,” a 1925 short story, hero Nick Adams asks about a once-famous boxer: “What made him crazy?” The old fighter’s friend replies, “He took too many beatings, for one thing.”

In The Sun Also Rises, published a year later, Nick describes losing a street fight: “He hit me and I sat down on the pavement. As I started to get on my feet he hit me twice. I went down backward under a table.” Being decked three times reminded Nick of a schoolboy football game. “I had been kicked in the head.” After the game, “I was carrying a suitcase with my football things in it, and I walked up the street from the station in the town I had lived in all my life and it was all new… all strange.”

Reading Hemingway’s description of what football players call “getting your bell rung” rang a bell for me. In thirty years as a sportswriter I got to know Jim McMahon, the “punky QB” of the 1986 Super Bowl champion Chicago Bears, who was diagnosed with dementia at age fifty-three, as well as Seau, an All-Pro linebacker who was as jolly off the field as he was fierce on it. At forty-three, after years of increasingly erratic behavior, Seau shot himself. His brief life story had two postscripts: his brain showed clear signs of CTE, and he was posthumously elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Pittsburgh Steelers immortal Franco Harris died at seventy-two last year with no signs of brain damage — perhaps because he preferred to run out of bounds rather than bang heads with tacklers. But like other contact-sports veterans, Harris worried about the effects CTE may have had on him. He told me he’d spent years wondering when he might “lose my marbles.” If he misplaced his car keys, he would think, “Is this how it starts?”

Hemingway went through that and more. By 1960 he felt he was a shell of his former self. Asked to write a short comment for John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in January 1961, he wept and said, “It just won’t come anymore.” Six months later he said to his wife Mary, “Goodnight, my kitten.” She was asleep when he padded downstairs to the gun cabinet.

“He wasn’t the same after the second plane crash. You can hear the difference in his 1954 Nobel Prize acceptance speech,” Farah says. “Genetic factors and alcohol-related cognitive decline surely contributed. But I believe at least eighty percent of his trouble was CTE.”

There is no way to be certain. Unlike Seau and other football players who shot themselves in the chest in order to preserve their brains for postmortem exams, Hemingway’s suicide destroyed his brain.

But CTE provides an explanation, even a sliver of comfort, to his granddaughter.

“It makes a lot of sense,” says Mariel Hemingway. “I hadn’t realized he played football.”

Now sixty-one, the same age her grandfather was when he died, the Oscar-nominated star of Manhattan, Personal Best, Star 80 and other films grew up hearing about the so-called Hemingway curse. “As I child I heard, ‘here’s a family and they’re cursed!’ But I never said that. I don’t believe it. I think we can break genetic patterns.”

Like Farah, she attributes her grandfather’s decline to various factors. “He lived life very hard. That’s a factor for sure. Look at how he looked at sixty-one — like he was in his eighties. I think a lot of things contributed. He had amazing qualities — such insight! — but when that starts to go away, where are you? Who are you? He had paranoia late in his life, and at the time there was no way to understand the science of what was happening to his brain. Eventually you can’t fight it. The depression took over. He was known for courage, but how do you go up against those demons?”

Did Ernest Hemingway have CTE? “Yes,” she says. “I think so. And it helps explain some things about our family. It makes total sense that getting hit in the head has effects on the brain. It’s kind of a comfort to think it wasn’t just genetics.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2023 World edition.