Israel’s new government is a daring, possibly doomed but nonetheless fascinating experiment. Headed by tech millionaire turned nationalist figurehead Naftali Bennett and TV journalist turned voice of centrism Yair Lapid, Jerusalem’s 36th government is an ideological hydra.

Bennett’s right-wing national-religious Yamina party is joined by the secular liberals of Lapid’s Yesh Atid, along with Kahol Lavan moderates, Labor social democrats, Meretz socialists, and the Likud breakaway faction Tikva Hadasha, plus Yisrael Beiteinu’s secular right-wingers and Ra’am’s Islamic conservatives. This unwieldy rabble is held together by a coalition agreement to focus on areas of consensus — more investment in education, bumping up defense spending, cutting bureaucracy and regulation, tackling crime and unemployment in the Arab sector, getting more ultra-orthodox youth into work — and swerve thornier matters, especially religious affairs and IDF service.

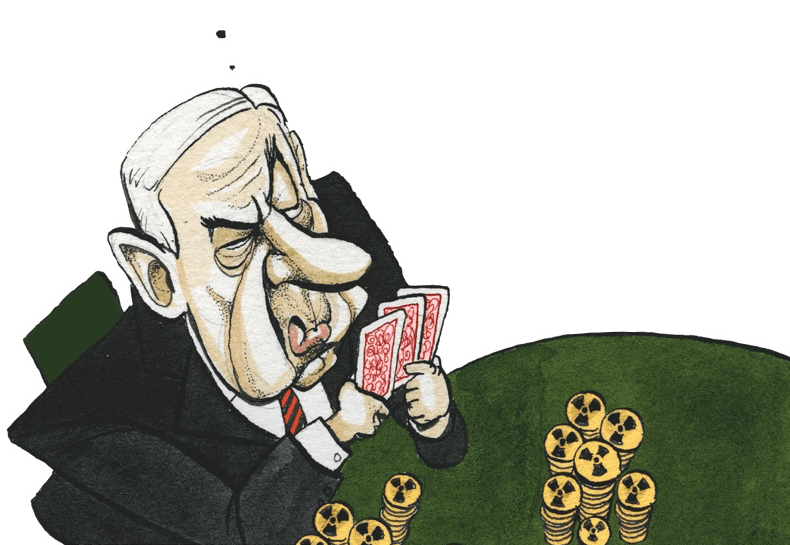

They’re also held together by something even more binding than their governing pact: the desire to oust Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s longest-serving prime minister. Bibi didn’t go down without a fight, warning: ‘We’ll be back soon.’

It may not be an idle threat. Bibi has been ousted before with the tacit (and not-so-tacit) support of a Democratic White House, though in 1999 he was at least beaten at the ballot box. This time, he has gone after two-and-a-half years of political stalemate and with a corruption trial pending. His street-fighting ways, which had served him so well in the past, eventually convinced enough of his natural right-of-center allies that he had to go — not least his railing against the police, prosecutors and the judiciary. He is 71 and awaiting his day in court, which makes it less likely that Israel’s comeback kid will stage another return, though throughout his political career one of Bibi’s greatest strengths has been his opponents’ tendency to underestimate him.

Bibi’s legacy is mixed. Much like Boris Johnson in Britain, he handled the initial months of the pandemic poorly but got the vaccine program right: Israel is now all but free again. He steered a strong economy, though his critics say he simply benefited from the economic reforms of the early 1990s. On his watch, Israel enjoyed improved diplomatic relations with Russia and China, broader recognition for Jerusalem as the capital city and a recent surprise turnaround in European attitudes. His foreign policy record will be best remembered for the Abraham Accords and Israel’s other normalization agreements with Arab and Muslim countries.

However, his greatest foreign policy failure is Iran. Bibi saw the threat of the Islamic Republic as a nuclear power years before other world leaders and Middle East experts, yet while he put up a tremendous fight, he failed to stop the Obama administration authorizing the Iran deal, which the Biden administration looks set to rejoin. If you want an indication of how sore he feels about this, he used his final speech yesterday to draw a parallel between Biden’s Iran stance and FDR’s refusal to bomb the railroad tracks to Auschwitz when American Jewish leaders begged him to.

Bibi talked a good game on Eretz Yisrael but action was less evident. His pledge to apply Israeli law to the Jewish communities in Judea and Samaria came to naught. While settlement expansion picked up eventually, his record on building over the Green Line was for a number of years more sluggish than even past left-leaning governments. Perhaps the most damning verdict on his ‘land of Israel’ policy is that the new government has adopted it as its own, the Netanyahu position on settlements being so rhetorically heavy and construction light that even leftist and Arab parties can’t get worked up about its continuation. There is a lesson here for the contentless conservatism of Boris Johnson, which may win elections but does little to move the country in a lasting rightwards direction.

Bibi also leaves behind a sectorally divided Israel and if the new government looks like the model UN, it is because a period of intense cooperation is now needed between sectors and factions. The necessity of this was underscored during the recent unrest, which saw not only Palestinians rioting in Jerusalem but Israeli Jews and Israeli Arabs clashing in cities like Lod.

All of this is rather a lot for Bennett and Lapid’s rotation government (Bennett will be PM until 2023 and Lapid from 2023 to 2025) to be getting on with. Bibi has already hit Bennett on leadership, claiming his former chief of staff lacks ‘international stature’, which is true not only of Bennett but of Lapid too. The two men will be extended some good will from foreign capitals, elated to finally be rid of Netanyahu. But that won’t do them a whole lot of good when Israel next has to bomb Hamas in Gaza or take out a nuclear reactor in Syria — or even Iran. The challenges facing Bennett and Lapid, domestically and internationally, are towering and neither has been sufficiently tested to be confident of how they will handle them. This will be a learn-on-the-job affair.

There is every chance this experiment could fail and Israelis end up missing Bibi. (He may have been a demagogue but you knew where you stood with him). Yet if Bennett and Lapid can make it work, they will have initiated a new era in Israeli politics and national life, not just a different government but a different way of governing, one that includes Israelis from all sectors and strives towards a greater national unity.

Urging his celebrating supporters not to ‘dance on the pain of others’, Bennett yesterday pledged his would be ‘a government that will work for the sake of all the people. We will do all we can so that no one should have to feel afraid. We are here in the name of good and to work.’ There is much good and much work needing done.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.