The media are abuzz these days about a purported “return to the 1970s.” Generally speaking, such chatter is not intended kindly, for many today would likely agree with the sardonic assessment of the Seventies made by the editors of New West magazine as that decade wound down: “It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times.” And not just because of the popularity of bell-bottom pants, platform shoes, and disco music. In the Seventies, we had problems far more troubling — more troubling even than the pop group ABBA.

For starters, we saw a quadrupling of real oil prices between 1973 and 1979. We suffered high rates of both inflation and unemployment, which hitherto varied inversely, leading to the creation of the portmanteau “stagflation.” Recessions marked the beginning (1969-1970) and end (1980) of the decade, with another — longer and even more serious — recession (November 1973-March 1975) in between.

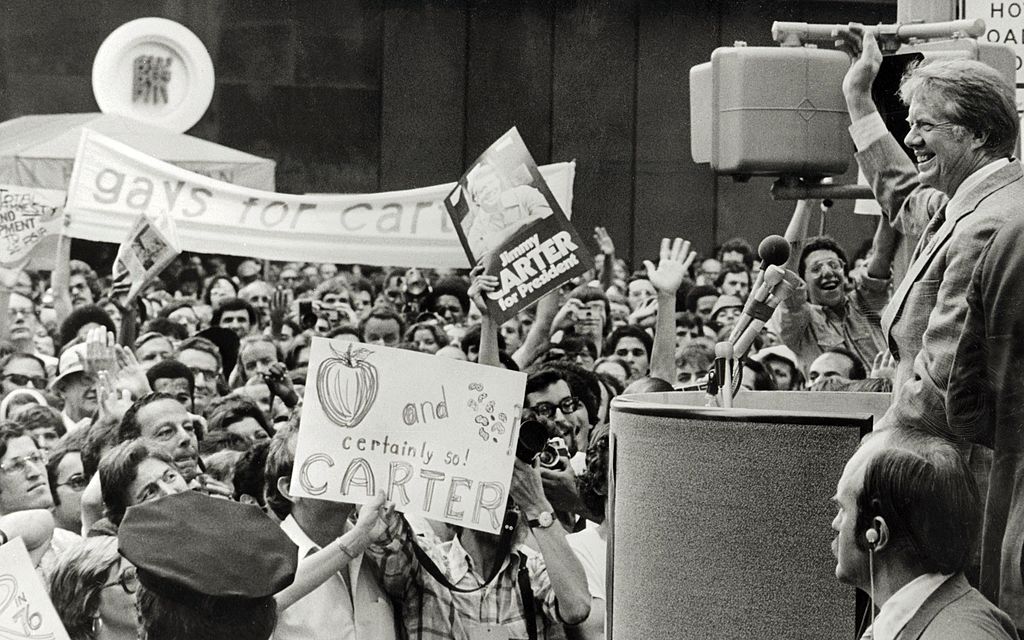

Rising crime rates, racial protests, social fissures. An unpopular foreign war that ended badly, problems with Russia, fear of a rising Asian economic powerhouse. Iran being a pain in the ass. A sense of cultural pessimism, exacerbated in the latter part of the decade by a weak Democratic president, who suggested in 1979 that the United States was suffering from “a crisis of confidence,” implying that the country was in a state of malaise, even as he felt our pain.

Cut to the situation today. On the surface, at least, there do in fact seem to be a number of similarities between our present predicament and that of the 1970s. Oil prices are again on the march, inflation is proving increasingly problematic, and in 2020 we went through a short Covid-19 recession. Crime rates are again rising, race relations are tense, and the social rift has become a chasm. Another unpopular foreign war has ended badly, we’re again having problems with Russia and, once more, we are alarmed by a rising economic powerhouse in Asia. And Iran is still a pain in the ass.

According to Pew, the US population is becoming increasingly pessimistic, and another weak Democratic president, Joe Biden, is at the helm. The president’s first major speech to the American people — on March 11, 2021 — has become known as the “empathy” speech, focused, as it was, on Mr. Biden’s assurances that he, like Jimmy Carter forty-odd years earlier, felt our pain. And earlier this year, veep Kamala Harris acknowledged to journalist Judy Woodruff that the American people were experiencing a “level of malaise.” Déjà vu all over again?

Maybe, maybe not, for glib media comparisons seldom withstand closer scrutiny. Admittedly, a few of the parallels do hold up reasonably well: our sour relationship with Iran is one example, and the shambolic way in which we quit unpopular wars in Vietnam and later in Afghanistan another. I’m not sure I’d call it malaise, but many people seem rather uneasy and pessimistic these days, which reminds me of the old Russian joke about an “average” year in the Soviet Union: worse than last year, but not as bad as next!

However, most of the Seventies comparisons demand qualification: rising oil prices, for example. While prices are increasing today, as they did in the Seventies, the relative importance of oil has diminished, along with the energy intensity of our economy. The amount of oil needed to produce $1,000 of GDP fell by over half between 1973 and 2019.

Similarly, while inflation plagued the US economy throughout the Seventies and has been on the rise again since November 2020, there are major differences between the forces pushing prices up in the two periods. Moreover, important promoters of sustained inflation in the 1970s — strong unions and the widespread presence of COLAs (cost-of-living adjustment provisions) in labor contracts — have been dampened considerably.

There are other differences too. Economists know a lot more today about the corrosive effects of expectations on the course of inflation. The private savings rate was generally higher in the Seventies and, while unemployment was high in that inflationary period, its level is quite low today. Thus, when high-profile economists such as Olivier Blanchard and Larry Summers speak about the possibility of “secular stagnation,” they mean something very different than the stagflation that plagued the US economy in the 1970s. And one other difference: we currently have no analogue to the WIN (Whip Inflation Now) buttons introduced by President Gerald Ford in 1974 to wear as talismans, thereby steeling our resolve.

Additional context is needed in making other comparisons as well. Although black protest was a big deal in the Seventies and is again today (at least spasmodically), the conditions informing protests are quite different. Whereas in the Seventies black protests could be seen as a continuation/consolidation of the Sixties movement for economic inclusion and basic civil rights, blacks by and large have now achieved these ends. They vote in high numbers; there are thousands of black officeholders; we’ve had a black president; and the median household income for black families in the US — $45,870 in 2020 — is now higher than median household income in numerous developed countries in the OECD.

What about crime? Here again, it is true that the United States witnessed troubling increases in the crime rate in both the 1970s and in recent years. But it needs to be kept in mind that even with the crime spikes during Covid, levels and rates of crime are much lower today than they were during the felonious 1970s and 1980s.

As for foreign policy: again, context matters. Despite the threats during both periods from economic powerhouses in Asia, the threat posed in the 1970s was less extensive, and the threatening party, Japan, was far less antagonistic and menacing than is the threatening party today, the PRC. And while our relations with the Bear were hardly warm in the 1970s, US-Soviet relations during the decade of “détente” seem downright balmy in comparison to our icy entanglement with Putin’s Russia today.

Bottom line: talk of a return to the 1970s needs to be disciplined. But how? Not to be academic or nerdy, but in 1986 — one year after the box-office smash Back to the Future was released — Harvard profs Richard E. Neustadt and Ernest R. May published a book called Thinking in Time, wherein they offered up some very useful tips for making good, quick historical comparisons. Ask what’s the story and when did it begin. Draw up a list of likenesses and dissimilarities between the situations or periods being compared. Ask what the authors call “KUP” questions: what is known? Unclear? Presumed? Doing these things can help one avoid loose comparisons, bad historical analogies — not all historical actions are subject to “domino effects” and not every negotiation leads to “appeasement” — and inappropriate or uncontrolled extrapolation.

Every time we see a spurt of inflation or a jump in oil prices we aren’t returning to the Seventies. But if you spend a few minutes googling, you’ll find glib “return-to-the-Seventies” comparisons made repeatedly since that decade ended. That said, there are, as we have seen, some real similarities between that decade and the situation today. Some real differences, too.

I must admit that I find one “similarity” particularly unnerving. ABBA, alas, is still with us: in 2021 the band released a hit LP entitled “Voyage,” which will be followed up by a “concert residency” in London featuring ABBA avatars later this year. Don’t miss it.