Elon Musk revels in the role of “free speech absolutist.” Last week, for instance, he jumped to the defense of Pavel Durov, the head of the messaging and social media app Telegram, after he was arrested by the French police. But while Musk claims he is a defender of free speech, he frequently kowtows to the Chinese Communist Party, for whom the concept is alien.

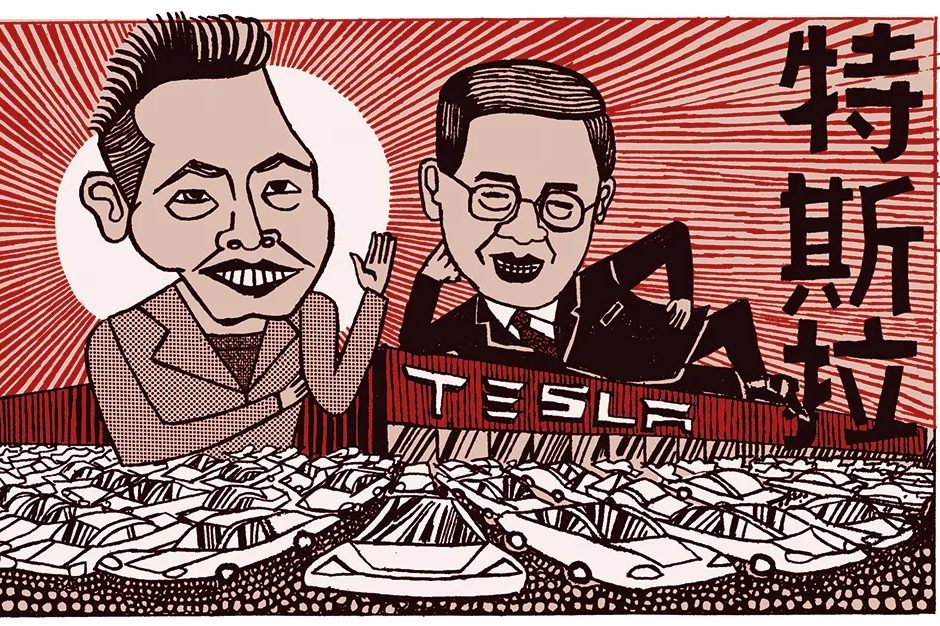

Musk is now the CCP’s favorite western capitalist. So although he is eager to tell his 196 million Twitter followers that “Britain is turning into the Soviet Union,” he has avoided antagonizing China. He has echoed CCP talking points on contentious issues, such as Taiwan and artificial intelligence, while remaining silent on China’s human rights record.

He is afforded all the trappings of a head-of-state visit during his trips

As such, he is afforded all the trappings of a head-of-state visit during his trips to China. Top ministers, corporate bigwigs and other party functionaries are all ready to greet him. State media fawns over him (one report even included a blow-by-blow account of a sixteen-course meal he enjoyed in a top Shanghai restaurant).

In April, when Musk last jetted to Beijing, he was taken to meet the Chinese premier Li Qiang, from whom he reportedly won an agreement to offer Tesla’s most advanced self-driving software on cars in China — software seen as critical for the future of the company, but which had been greeted with caution by American regulators.

The following month, Tesla broke ground on a vast new manufacturing plant in Shanghai to make batteries. It’s close to Musk’s existing car plant, which produces a million electric vehicles (EVs) a year and is the company’s most important export hub, responsible for more than half of worldwide sales.

“Honored to meet with Premier Li Qiang,” Musk enthused on Twitter during that visit. “We have known each other for many years.” Li, China’s most senior official after Xi Jinping, is the matchmaker in Musk’s China romance. As CCP boss of Shanghai in 2018, he eased Tesla’s way into the city.

The factory was approved and built at astonishing speed, constructed in under a year, aided by tax breaks from Beijing and cheap loans from state-owned banks, while Tesla was allowed to wholly own its Chinese operations. The company was even permitted to begin production before securing all its permits. “China rocks,” declared Musk, shortly after the factory opened, praising the “smart, hard-working people of China,” whom he contrasted with the “complacent” and “entitled” Americans.

During the disruption of Covid lockdowns, the authorities helped Tesla continue running, bussing in workers from secure dormitories and ensuring a generous supply of masks and other protective gear. While Musk criticized “fascist” lockdowns in America, which amounted to “forcibly imprisoning people in their homes,” he had nothing to say about those in China, which were the world’s most draconian. Instead, he thanked Beijing for the “support and protection.”

Tesla’s China investments go well beyond production facilities. In June 2022, Grace Tao, Tesla’s global vice president, told the third Qingdao Multinationals Summit, a business forum, that the Shanghai Gigafactory, as Tesla’s EV factory is called, was not only set to source more components locally but would also establish research and development and data centers in China. “The R&D center will be Tesla’s first vehicle innovation R&D center outside the United States,” she declared.

Musk’s support has been eagerly leveraged by Beijing at a time when western politicians and other corporate bosses are becoming more circumspect about their relationship with China and American technology curbs are beginning to bite. Shortly after Musk met China’s foreign minister last year, a ministry statement said that Tesla “is opposed to decoupling and cutting off supply chains and is ready to continuously expand business in China.” Musk praised the “vitality and potential of China’s development… despite Washington’s reckless technology decoupling maneuvers,” according to a Chinese government readout of the meeting.

Musk also says Beijing is “on Team Humanity” as regards artificial intelligence, despite AI’s ability to turbocharge China’s disinformation, surveillance and cyberspying. He told the opening ceremony of a Shanghai AI conference via video link: “I’ve always been a tremendous admirer of the sheer amount of talent and drive that exists in China. So, I think, really, China’s going to be great at anything it puts its mind to.”

When Xi visited the US in November, Musk posted a photograph of himself shaking hands with the Chinese leader, alongside the caption: “May there be prosperity for all.” He has waded into China-Taiwan tensions too, claiming Taiwan is an “integral part” of China. He suggested it should become a special administrative region of the People’s Republic, a view that was criticized on the island as dangerous and naive. Tesla has also opened a showroom in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang province, where the CCP has been accused of slavery and genocide, leading to Musk being accused of complicity in the repression of the Uighur people. Tesla posted pictures online of staff at the opening ceremony holding signs reading “Tesla Loves Xinjiang.”

In his biography of Musk, published last year, Walter Isaacson describes a conversation in which Musk said there are “two sides” to China’s repression of the Uighurs. The conversation took place between Musk and Bari Weiss, a journalist who’d been hired by Musk but was increasingly uneasy about her boss. When Weiss quizzed him about whether his business interests might conflict with his 2022 purchase of Twitter, “Musk got annoyed,” writes Isaacson. “Musk said that Twitter would indeed have to be careful about the words it used regarding China, because Tesla’s business could be threatened.”

Although Twitter is banned in China, the CCP makes considerable use of the platform for propaganda and disinformation, both through the accounts of its diplomats and party-run media, and via the widespread covert use of an army of fake profiles and bots. In what seemed to be a shot across Musk’s bows, Chinese state media, usually so flattering, attacked the Tesla boss for retweeting a post appearing to endorse the highly plausible theory that the Covid pandemic might have originated with a leak from a Wuhan lab. The Global Times warned Musk against “breaking the pot of China” — a saying akin to “biting the hand that feeds you.” The “free speech absolutist,” so quick to the draw when confronting his western critics, did not respond.

Musk’s stewardship of Twitter has caused anxiety among high-profile Chinese dissidents in the West. Ai Weiwei, the exiled artist, has been scathing, cutting down on his use of the site and mocking its new X logo as authoritarian. He posted an animation in which the X spins and then turns into a swastika, which was promptly deleted from the platform. “[Musk] wants to show his ambition, you see his performance here is really about a lot of personal ego I think,” Ai told me at the time.

According to Musk, there are ‘two sides’ to China’s repression of the Uighurs

While the CCP is very grateful to have such a high-profile cheerleader, its motives for showering favors on Musk go deeper.The decision to host the Gigafactory in Shanghai has brought arguably the world’s most innovative company to China. It has also hastened the development of local EV supply chains and galvanized China’s own industry in a technology where the CCP wants to lead the world. To seasoned China-watchers, it is a familiar strategy — a foreign partner becomes infatuated with the Chinese market, and Beijing is willing to grant selective favors in an area where it needs tech and expertise.

And it is all going according to plan. China’s EV industry now threatens to devour the company that helped create it. The Chinese giant BYD, once mocked by Musk for its poor technology and ugly cars, is challenging Tesla for global supremacy. Price wars triggered by massive overcapacity (in part the result of enormous state subsidies) are eating into Tesla’s market share and profits. Net income for the second quarter of this year fell 45 percent to $1.47 billion.

Tesla is also beginning to face other familiar challenges. It recently accused a Chinese chip designer of stealing technology secrets, and Tesla cars were banned from military and government facilities because of security fears over the vehicles’ cameras and sensors. In fact, these restrictions reveal a greater awareness by the CCP than in the West of the dangers (or opportunities) that fully connected EVs, essentially computers on wheels, represent for surveillance and espionage. Musk gave only a muted response, insisting that his company would never use the technology for spying.

It would be easy to dismiss Musk’s China infatuation as a common case of corporate Stockholm syndrome. In fairness, that syndrome masks a range of other conditions. Fear, pragmatism, opportunism, cynicism, greed, naivety — you will find them all in corporate dealings with Beijing. Musk is perhaps the perfect embodiment of that complexity.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.