Donald Trump has never lacked confidence. “I’m here to get the thing over with,” he said last week when announcing the meeting with Vladimir Putin. “President Putin, I believe, wants to see peace. And Zelensky wants to see peace. Now, President Zelensky has to get… everything he needs, because he’s going to have to get ready to sign something.”

To many, that sounded like a variation on Trump’s much repeated election claim that he would end the Ukraine war in 24 hours: a grandiose statement that will probably bear little if any fruit this week. Indeed, the smart money is on the Alaska summit resulting in claims of a “historic breakthrough,” which will change little on the front lines.

One of the challenges when assessing Trump’s administration has been how to separate the signal from the noise. The President’s personality and his stream of consciousness comments often give the impression of a man operating on instincts. Trump’s transactional instincts, though, made him think Putin would behave in a logical way – that the Russian leader would welcome the chance of a reset to calm an overheating economy, move Moscow away from the horrors of an estimated million men killed or wounded, and bring Russia back into the family of nations.

The fact that, until now, Putin has rejected Trump’s overtures is revealing about the former’s view of the strength of his hand – as well as a misreading of his opposite number, something that is regularly reinforced in the Russian media’s lampooning of Trump.

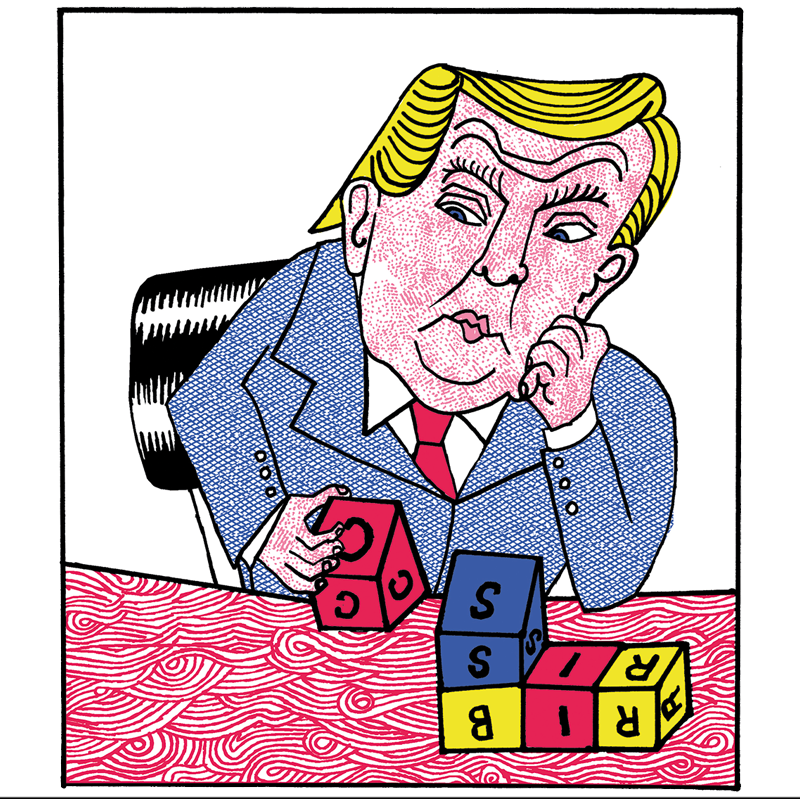

The President may have taken his time to play his cards, but he’s chosen a good time to play them – and not only in the case of Russia. The Alaska summit isn’t just about Ukraine: it’s a key point in an elaborate, even existential game of geopolitical chess that will define the coming decade, if not longer. It’s about Trump vs BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

Few paid much attention when the foreign ministers of Brazil, Russia, India and China first met on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York in 2006, at the first summit in Yekaterinburg in Russia three years later, or when South Africa joined in 2010 to form the BRICS grouping. This has subsequently expanded to ten full members, with Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates joining as full members last year and Indonesia joining in January.

BRICS represent half the world’s population and 40 percent of its GDP in terms of purchasing power

Taken as a group, BRICS represent around half the world’s population and some 40 percent of its GDP in terms of purchasing power parity. Although the aims and ambitions of its members diverge on many topics – including on what BRICS can and should do – the underlying theme is that global economic power needs to be passed from the West to the developing world, and that, as a result, a more balanced global order will emerge.

Trump has had the BRICS group in his sights for a while – especially the possibility that they might act to create an alternative to the US dollar. Soon after last year’s election, he declared: “We require a commitment from these countries that they will neither create a new BRICS currency nor back any other currency to replace the mighty US dollar, or they will face 100 percent tariffs and should expect to say goodbye to selling into the wonderful US economy.” For BRICS to succeed, he said, they would need to “go find another sucker.”

Trump has repeatedly returned to the BRICS problem. “BRICS was put there for a bad purpose,” he said earlier this year, shortly before meeting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Indeed, the BRICS bloc provides, if not all, then at least a major part of the framework through which Trump’s economic policy has been constructed. Just last month, he said that tariffs would apply not only to the BRICS countries, but to any that align with what he called their “anti-American policies.” He spoke about BRICS again soon after, saying that if the original members “ever really form in a meaningful way, it will end very quickly.” He added that the US “can never let anyone play games with us.”

It’s no coincidence, then, that the efforts to push Russia into a settlement in Ukraine are taking place now. Trump announced 50 percent tariffs against Brazil – something that led to President Lula da Silva, tellingly, to say he would confer with fellow BRICS members. Likewise, the President has said he will probably “send someone else” to the G20 meeting being held (for the first time) in South Africa because of that country’s “bad policies.”

The President ’s main concern is the group might act to create an alternative to the US dollar

Trump also knows that Russia’s economy is in a bad way. The US having used tariffs to squeeze Putin’s allies in BRICS, Moscow looks increasingly vulnerable. Indeed, recent economic news coming out of Russia is bad. Elvira Nabiullina, the governor of the central bank, warned in June: “We have adapted to some external challenges [but] now we are facing very turbulent times ahead.” Putin himself expressed that Russian officials not only had to be vigilant “not to allow stagnation or recession,” but also that it was crucial for Russia to “change the structure of our economy.”

Although interest rates have been trimmed back to 18 per cent, things continue to look bleak. More than 50 coal producers have either closed or are closing. Steel production among the largest producers is down by a fifth, year on year. The chief executive of Domodedovo airport, one of the busiest in Russia – and, before the war, in Europe – is close to bankruptcy.

Unseasonable frosts followed by extreme drought have had a dramatic impact on grain and food production, which have seen prices spike. The shortfalls compared with previous years are impacting Russia’s export economy and its foreign currency earnings.

This comes on top of concerted action by the European Union to move away from Russian natural resources. A decade ago, Russia’s trade with the EU totaled around $420 billion a year. With sanctions, that had plummeted to roughly $60 billion last year; it’s projected to shrink further to only $40 billion this year. Alexander Grushko, the deputy foreign minister, warned last month that trade with the EU – once a linchpin of Russia’s economy – could “fall to zero” if current trends continue.

Perhaps the best example to show the strain that Russia is under comes from seeing who sits behind its war economy. An estimated 40 percent of ammunition used on the front lines is supplied by North Korea – and significantly more in some places. Zvezda TV, a state-owned network run by the Russian defense ministry, has shown films of teenagers working in drone factories in Tatarstan, a region which has just seen the influx of a small army of industrial workers from North Korea – estimated to be 25,000-strong – to work as technicians, machinists and electronics assemblers.

For all of Moscow’s tough talk, the reality is that minds are more focused than they have been since the start of the invasion. That’s why substantial groundwork has been done over the past few weeks – and why there’s more to the Alaska meeting than a photo opportunity.

Trump’s push to get Russia to agree to a settlement – and the US’s efforts to encourage Kyiv to accept it – are part of a wider attempt to reshape the emerging multipolar new world order. Trump is not just gunning for Russia; he is trying to use US firepower against BRICS at the same time.

Of the BRICS grouping, India is one country that Trump has had in his sights for a while. In 2020, relations between Trump and Modi were unusually warm. India was “one of the most amazing nations,” Trump declared. Things were similarly sweet when Modi visited the White House in February. Just as Trump sought to Make America Great Again, Modi was seeking to Make India Great Again. “When America and India work together, this MAGA plus MIGA becomes a mega partnership for prosperity,” Modi said.

Trump has decided, however, to show that American power can focus minds. As India’s veteran external affairs minister S. Jaishankar put it, India sees its role as being to “engage America, manage China, cultivate Europe, reassure Russia, bring Japan into play, draw neighbors in, extend the neighborhood, and expand traditional constituencies of support.”

That sounds sensible; but balancing acts are tricky to pull off. Deep ties between Moscow and Delhi, which go back to before Indian independence and which remained strong during the Cold War, have been maintained since the fall of the Berlin Wall. India pointedly abstained from a vote at the UN to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and has abstained on subsequent occasions, too.

Apart from membership of BRICS, the heavy dependence on Russian military hardware – including the delivery of two warships built in Russian shipyards in recent months – and a formal agreement reached between the two countries at the end of 2023 to deepen collaboration, India has seen its trade with Russia boom in recent years.

Before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, trade between the two countries stood at around $12 billion a year; by the end of 2023, it had quintupled to $65 billion. Much of that was through the purchase of discounted oil – a great deal of which has in turn been sold on to markets elsewhere. So great have volumes been that India has overtaken Saudi Arabia as the biggest supplier of oil to Europe – impressive given that India is only a modest producer in its own right.

That realisation is why Trump turned on Delhi last week, announcing a 50 percent tariff on Indian goods. India operates “strenuous and obnoxious trade barriers,” he said.

But it was the fact that Delhi is siding with Moscow that underpinned his change of pace. The Indian government doesn’t “care how many people in Ukraine are being killed by the Russian war machine,” Trump said. Russia and India “can take their dead economies down together, for all I care”. While officials in India said the US charges were “unfair, unjustified and unreasonable,” Trump used the opportunity to announce a new trade deal with Pakistan, adding that the US would help develop the latter’s “massive oil reserves,” and that perhaps one day Pakistan will be “selling oil to India”.

This is part of a coherent effort to use US economic and political power to frame the world of today and tomorrow. There is intention, in other words, behind the lining up of different pieces of the geopolitical jigsaw at a time when, as Xi Jinping told Putin: “There are changes, the likes of which we have not seen for 100 years.”

Trump is not just gunning for Russia; he is trying to use US firepower against BRICS at the same time

Together with China and their fellow BRICS members, Putin believes that Moscow is driving these changes. Trump feels that the US needs to stand in the way.

At a Senate hearing shortly before Trump’s inauguration, the Secretary of State-designate Marco Rubio made the telling claim that “the post-war global order is not just obsolete, it is now a weapon being used against us”. He reiterated this at Nato headquarters in Brussels a few weeks later. This is why it is so essential to “reset the global order of trade,” he said.

The view that we are in an age of existential competition is shared elsewhere. The influential Chinese scholar Liu Jianfei argues that not only is there a “great game” under way between rival superpowers, but this represents “a contest between national governance systems and the direction of global governance and international order.”

The Alaska summit is a key moment in that contest – perhaps even a turning point.

Of course, there’s a giant piece of the jigsaw missing here – and with good reason: China. The shadow-boxing between Trump and Xi is more nuanced, more intense and more evenly matched. That is where the battle over the global order goes next.

For now, the question will be whether Trump’s grand strategy to break up the emerging multipolar order has enough force behind it to deliver the results he is hoping for. Or whether it might in fact strengthen, rather than weaken, those countries who feel their time has come.

Leave a Reply