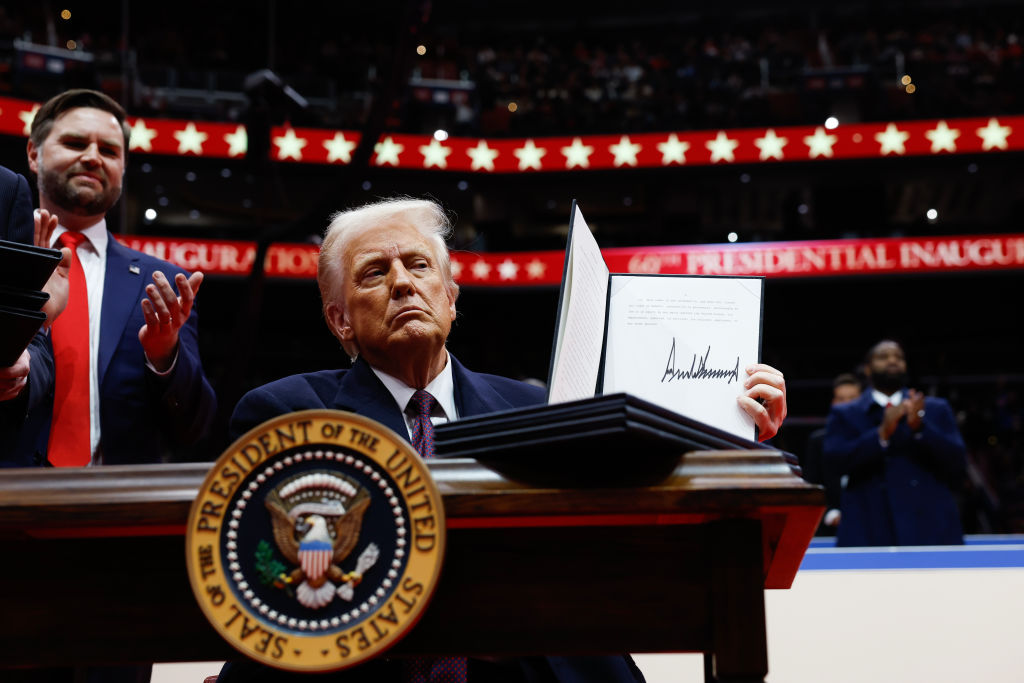

President Donald Trump wasted no time implementing his agenda after taking the oath of office on Monday. He’s issued more than two dozen Executive Orders (and counting), touching everything from immigration to affirmative action to trade.

The orders may align with his campaign promises, but underscore a broader trend in American politics: the increasing reliance on executive power over congressional votes. The attitude is far from new.

The rise in Executive Orders can be traced back to the beginning of the twentieth century. Theodore Roosevelt issued 1,005 Executive Orders from 1901 to 1909. Woodrow Wilson wrote 1,767 from 1913 to 1921. Herbert Hoover issued 1,003 from 1929 to 1933. Franklin Delano Roosevelt put it this way during his first inaugural address in 1933: with the country grappling with the Great Depression, it was time to show Americans he would “do something” about it.

“[I]n the event that the Congress shall fail to take one of these two courses… I shall not evade the clear course of duty that will then confront me,” declared Roosevelt. “I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis — broad executive power to wage a war against the emergency.” FDR issued 3,737 Executive Orders from 1933 to 1945.

By the late 1990s and onwards, White House advisors and presidents openly declared their love of Executive Orders. “Stroke of the pen. Law of the land,” quipped Paul Begala, then counselor to Democratic president Bill Clinton in 1998. “Kind of cool.” Begala was explaining how Clinton would remain an effective president despite his recent impeachment. Clinton issued 364 Executive Orders from 1993 to 2001.

President Barack Obama buoyed the pen and phone argument more than a decade later when he found himself dealing with a Republican-led Congress. “We are not just going to be waiting for legislation in order to make sure that we’re providing Americans the kind of help that they need,” he told reporters in 2014. “I’ve got a pen… to sign Executive Orders and take executive actions and administrative actions that move the ball forward…” Obama issued 277 Executive Orders during his two terms in office.

Executive Orders may be an easy way for presidents to direct their agenda; however, Gene Healy with the Cato Institute explained their use causes wild vacillations in federal policy. The ban on US foreign aid dollars from being used to promote or perform abortions. It was implemented in 1985 by Republican president Ronald Reagan via Executive Order but rescinded by Clinton in 1993. Since then, GOP and Democratic presidents have played a game of EO hot potato — reimplementing and rescinding it as the White House changes parties.

“At some point you have to ask yourself, ‘Is this any way to run a country?’ because we’ve always heard that elections have consequences,” Healy told me. “It really raises the stakes of presidential election, I think, in a way that’s very dangerous.”

Meanwhile, Congress acts more like elected advisors versus policy makers. It’s true they’ll vote on continuing resolutions to keep the government open and certain popular bills like the Laken Riley Act.

But they’re mostly absent from proposals that could be seen as controversial — including bills that cut spending, reduce the $36 trillion national debt or reform mandatory spending programs like Social Security and Medicare.

“These are real problems that will determine the prosperity of the United States in the next decade. The failure to act now on these and other issues is a dereliction of duty,” said Jason Pye, a senior policy advisor at the Independent Center.

Pye said it used to be a joke that Congress was unwilling to move on difficult issues, but that’s no longer the case. He warned the country will have to pay for its spending largesse at some point. “We may not like it when the bill comes due.”

What caused Congress’s cowardly lack of action is up for debate. For Pye, it’s the hyper-partisan nature of American politics. “Most members of Congress, Republican and Democrat alike, are completely held hostage by the base of their party. Fall out of line? You’ll get a primary challenge,” he said. Healy said activist groups have been part of American politics since “time immemorial” and that no one is going to find a single cause. “That’s what makes it a particularly thorny problem.”

It’s worth noting that some of America’s earliest political commentators worried the president would become akin to a king. Virginia governor Edmund Randolph, who became the first US attorney general, called the proposal for a single executive “the fetus of monarchy” at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. “The world is too full of examples, which prove that to live by one man’s will become the cause of all men’s misery,” opined the Antifederalist “CATO” that same year.

The Federalists swore there was no way the US would descend into tyranny due to an unrestrained presidency. Their ghosts are choking on those promises. The only way to avoid this would be for Congress to do its job and govern. Unfortunately, they don’t appear willing to risk their political careers. That puts America’s fiscal footing and its position as a “Shining City on a Hill” to the rest of the world at risk.

Leave a Reply