“Life to me has been bigger than any Hollywood film,” says legendary photojournalist Don McCullin when we meet to discuss his latest exhibition A Desecrated Serenity at New York’s Hauser & Wirth. But when I broach the subject of actual film in the works – a big Hollywood biopic involving director Justin Kurzel – McCullin would rather I didn’t: “I feel ashamed even thinking about it. If you celebrate your success, it’s damaging. I’ve always done what I’ve done because I wanted my father’s name to be important. I’ve done my best to tread the path and behave myself because his name belongs to whatever I do. He didn’t have a very long life, you see. He died at 40 when I was 13.”

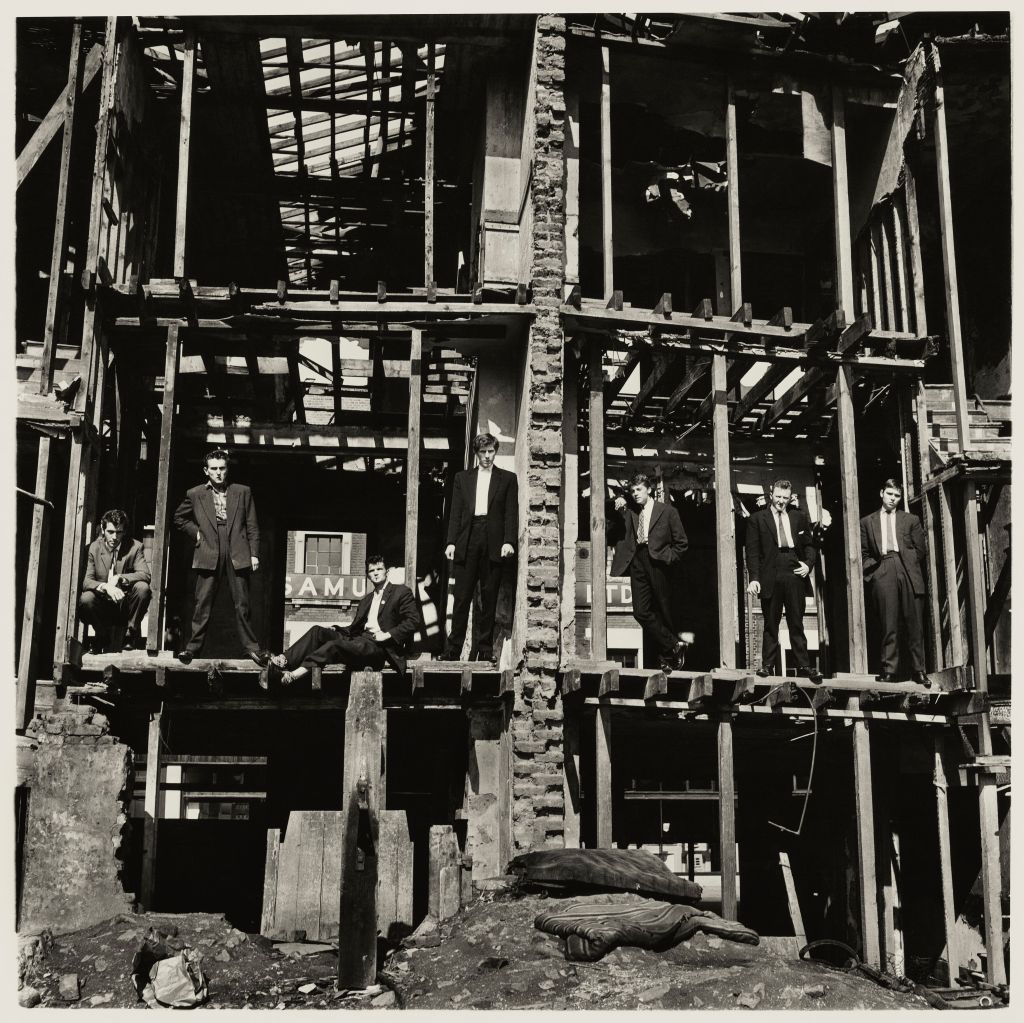

Sir Don McCullin CBE, who celebrated his 90th birthday last month, is rightly regarded as Britain’s greatest living photojournalist, renowned for his unflinching documentation of war, famine and human displacement. Born in Finsbury Park, North London, in 1935, he first picked up a camera during National Service in the Royal Air Force while working as a photographic assistant in aerial reconnaissance. But, having failed the RAF trade test to become a photographer, he didn’t get his first professional break until 1958 when his first published picture of a London gang called “The Guvnors” appeared in the Observer newspaper. This led to a contract with the paper, and in 1963 he was dispatched on his first official war assignment to Cyprus, where he experienced his “baptism of fire” as a photojournalist.

Between 1966 and 1984, McCullin worked for the Sunday Times as a staff photographer, a tenure that took him to the frontlines of war across Greece, Vietnam, Cambodia, Biafra, Bangladesh, Northern Ireland and Beirut. He produced some of his best-known work during this period, images that once seen are hard to unsee, such as “Starving Twenty-Four-Year-Old Mother with Child, Biafra,” and “Shell Shocked US Marine 1968.” He also experienced several close brushes with death – one item on display in this exhibition is the Nikon F camera he was holding to his eye when it absorbed a bullet from a Khmer Rouge soldier’s AK-47.

A Desecrated Serenity, McCullin’s most comprehensive US presentation to date, brings together over 50 works and rare archival materials. Harrowing images of war and suffering hang alongside stark industrial landscapes of Northern England in the Fifties and Sixties, portraits of The Beatles from their “Mad Day Out” photo session and compositions from his personal travels across India, Indonesia and the Sudan. Later work includes landscapes of France, Scotland and Somerset, where McCullin was evacuated as a child during the Blitz and where he now lives.

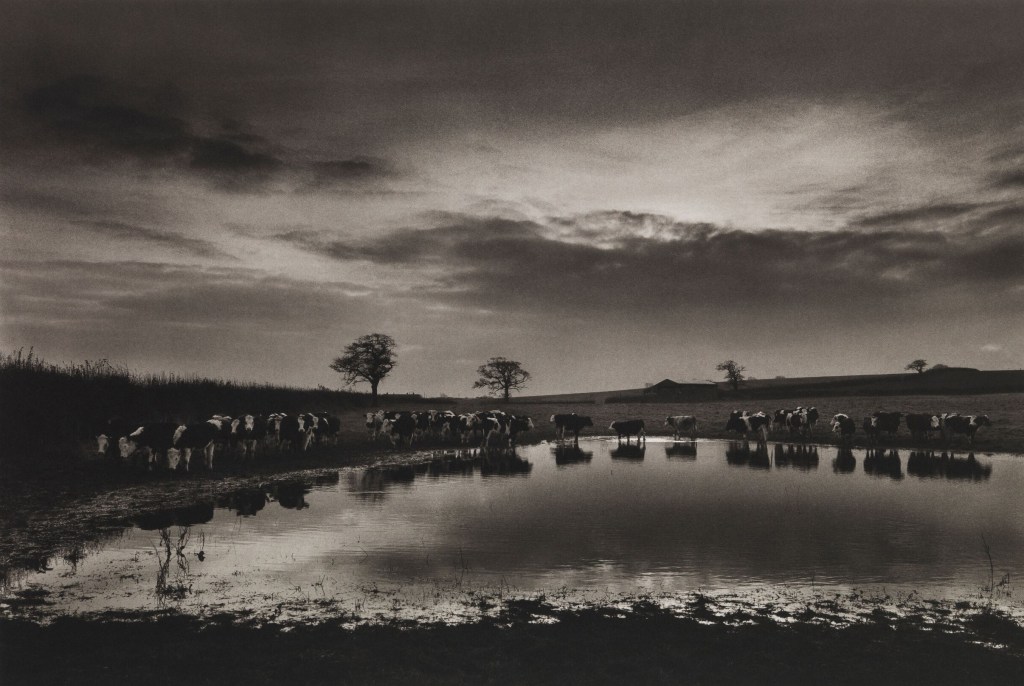

Rendered in his signature deep, dark tones, these painterly depictions of the English countryside – which McCullin has described as his greatest refuge – are worlds away from the battlefield but somehow echo his earlier work. On a windswept hill or in a flooded meadow in Batcombe Valley, McCullin has found his serenity, though it is a “desecrated serenity.” Just as McCullin is haunted by the destruction he has witnessed, so too are these calmer pictures. A sense of foreboding is never far away.

The same chromatic and emotional gravity carries over to a selection of still lifes inspired by the work of Flemish and Dutch Renaissance masters, as well as images of Roman statuary from McCullin’s “Southern Frontiers” series, his 25-year survey of the cultural and architectural remains of the Roman Empire. McCullin credits his late friend the author Bruce Chatwin with inspiring him to take on this mammoth project. With scant prior knowledge of the classical world (McCullin suffered from acute dyslexia and left school at 15) he decided to team up with author Barnaby Rogerson of Eland Books, and they began documenting all the Roman cities along the north coast of Africa, collaborating on two books: 2020’s In Search of Ancient Africa: A History in Six Lives and 2023’s Don McCullin in Turkey: Journeys Across Roman Asia Minor. It remains some of his proudest work. So far McCullin has produced over twenty books, including the 2007 autobiography Unreasonable Behaviour, and he is currently working on a big book on the Vietnam War.

McCullin is haunted by the destruction he has witnessed. A sense of foreboding is never far away.

For a man who has seen it all, McCullin is disarmingly lighthearted and modest, and he’s wary of the compliments and titles conferred upon him for his work (in 1993 he was the first photojournalist to be awarded a CBE; in 2017 he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his services to photography; this year he scooped the top prize at the London Press Club Awards). He recoils when I describe his images as iconic: “If you make a tragedy look too beautiful you’re not serving any purpose. I have a big moral question about my work. All these gongs, honorary degrees – in the end I don’t feel good because I shouldn’t be rewarded at the expense of somebody else’s suffering. Those pictures haven’t made the slightest difference to the world.”

But he will admit to one thing: a strong compositional eye. And he laments how people nowadays have largely stopped seeing the world around them, being glued to their phones. “My eyes have been the wealth of my mind, and I’ve interpreted everything through them. It’s got nothing to do with photography. People say, ‘Oh, what camera do you use?’ And I want to kick them up the backside! My photography is done purely emotionally. I’ve got good eyes; I can see things other people don’t see. They go about their lives looking at only one thing, their phone, so they’re missing the whole life around them. They think they’re getting information from their phone but it’s actually stealing their life away from them.”

As he enters his tenth decade, the veteran photographer shows no signs of slowing down. “I’m so pleased that I’m not in some old nursing home in Somerset. I can still wander over that last hill, climbing, gasping, which I’ve done a million times.” Three months ago, he was in Syria, visiting Palmyra for the fifth time. And he has just been invited to Antarctica to photograph the world’s largest icebergs: “I keep thinking about packing it in. I’m sick of going into my darkroom and standing in that lonely red light [McCullin does all his own printing]. But then someone comes along with the biggest carrot in the world and I’m like some old donkey who’s jumping in front of the others. I’m going to bloody Antarctica at 90.”

A Desecrated Serenity at Hauser & Wirth is up until November 8.

Leave a Reply