Attending a business summit in Shanghai earlier this year, I was struck by how downbeat the mood was. China’s stagnant economy, in particular the slow-motion meltdown of the property market, had clipped investor confidence across a number of industries. One Italian businessman told me the event had many fewer international attendees than previous years. But the apprehensive mood was cut through by the bolshiness of one senior executive from a leading Chinese electric car company: “America, Europe, Japan and South Korea are our high-potential markets,” the exec beamed as he set out a plan for what seemed like world domination.

His optimism was not misplaced. In post-pandemic China, electric cars have come out on top as a national success story. The market leader, BYD, sold more cars globally in the last three months of 2023 than Tesla. Chinese brands are expected to take a quarter of European new EV sales this year. The Chinese are so chuffed with the success of their electric cars that they are dubbed one of the “new three” (xinsanyang): EVs, solar panels and batteries. Past the age of mass production of clothes and toys, these are China’s champions in the 2020s.

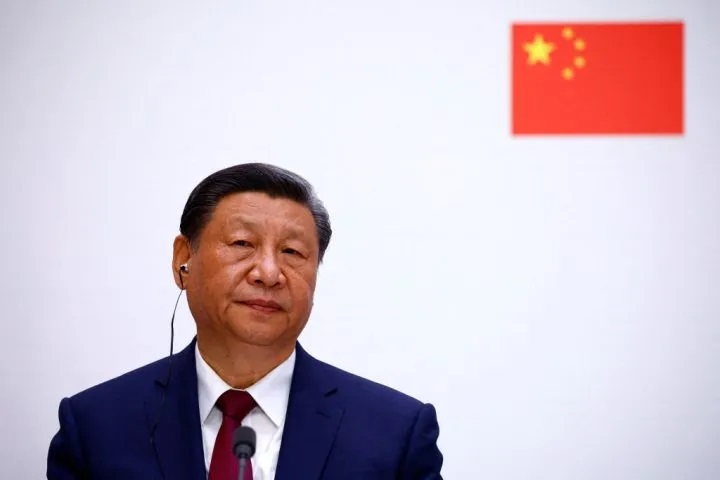

The Chinese government under Xi Jinping is not one for taking provocations lying down

This competitiveness is exactly what sows fear amongst American and European rivals. Last week, Joe Biden announced a raft of new tariffs on Chinese goods, the most eye-catching being a 100 percent tariff on Chinese electric cars, four times the current rate. In Brussels, the European Commission has begun a number of anti-dumping probes into Chinese EVs, solar panels and medical equipment. The commission’s president, Ursula von der Leyen, has so far resisted American entreaties to present a united front on tariffs, but has pledged to penalize Chinese companies if these investigations prove their low prices damage the EU economy. A new trade war has begun.

The Chinese government under Xi Jinping is not one for taking provocations lying down. To punish France for taking a leading role in the commission’s investigation into Chinese EVs, and for favoring French carmakers with subsidies not available to the foreign, China began an investigation into brandy imports (99 percent of which comes from France). On Sunday, China also launched an anti-dumping investigation into imports of a thermoplastic widely used by the US, EU, Japan and Taiwan in its car industries.

But ultimately, Beijing is limited in how much damage it can inflict. Its fundamental problem is that it exports much more to the US and EU than vice versa. What’s more, with its economy already in the doldrums, any revenge will hurt it too. China could go after German and American automakers, for example, who make up three fifths of its car imports, but that would hurt Chinese consumers, as well as the Chinese joint ventures that the foreign automakers partner with. Or it could target American grains and oilseeds, which account for two thirds of US exports to China by value and are protected by a powerful lobby in Washington, but that would also only hike prices for consumers and businesses at home. Protectionism hurts both sides, and in this case, as in Trump’s trade war, the West can afford to go lower.

It has also been suggested that China could target key electoral states in the US, hitting Biden where it matters in this crucial election year. A Swedish trade NGO has calculated that more than a quarter of Biden’s 2020 winning margin could be put at risk in Arizona, Georgia and Wisconsin if China blocked exports from those states and hurt local jobs. But would a Trump victory really be better for China, considering the former president is the original mastermind of a trade war against Beijing?

Ursula von der Leyen has repeatedly suggested that if China took a harder line on Russia, Europe’s relationship with Beijing would be better. But even if Russia surrenders tomorrow thanks to Chinese help, the scale of the economic and security challenges emanating from China have become too large for Washington and Brussels to ignore. In reality, this trade war has many more years to run.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply