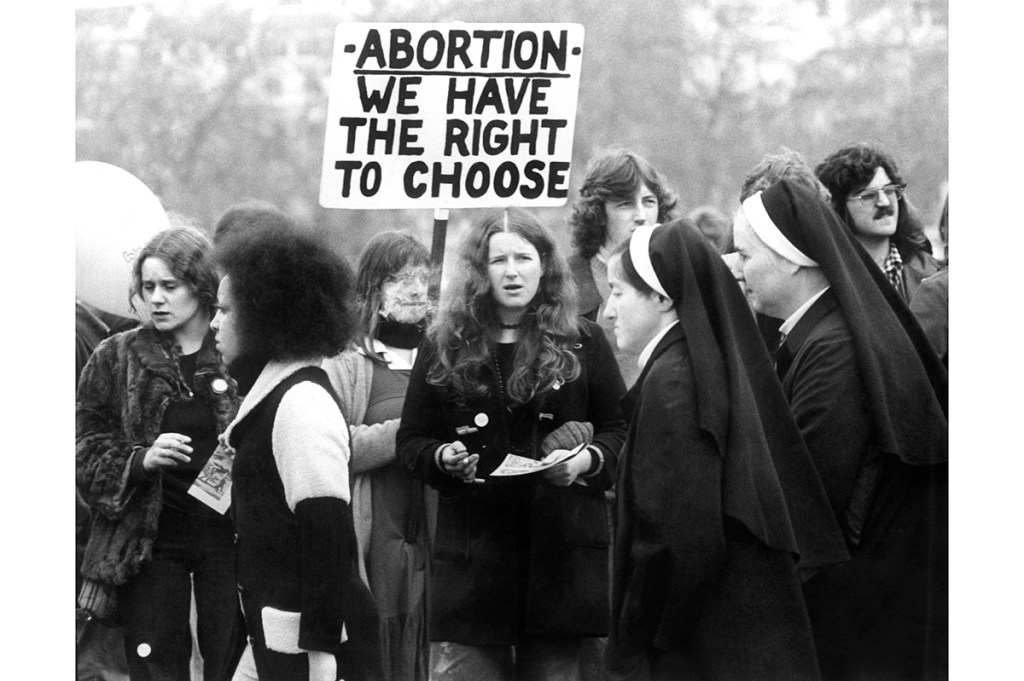

For nearly half a century, American politics has been defined according to the strictures of a single Supreme Court decision: Roe v. Wade. The 1973 case determined abortion policy for the entire nation, striking down state rules and creating a political movement in response which played out in unexpected and completely polarized ways.

It drove southern evangelical Christians and northern Catholics into unorthodox political partnerships. It cut across the Democratic Party coalition, leading to constant squabbling even through the passage of Obamacare. It led directly to the creation of the conservative legal movement, the elevation of prospective judicial nominees as of the utmost importance in assessing presidential candidates. And, due to the unexpected pragmatism of social conservative voters, it led to the election of Donald Trump.

With the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, all of that is now gone. What remains is a political landscape where the rules of the abortion battle are returned to where they were in 1972, a matter for states and local legislators to decide. It is a rare instance of a politically accepted status quo, presumed permanent by the political and consultant class even among those advocating for its change, being swept away in the blink of an eye.

For approximately half the states, little will alter in the short term. In major population centers like California and New York, the abortion regimes installed by Democratic politicians might push even further in the direction of taxpayer funding and permissiveness up until birth. But in the other half, limits will be pursued; they are already being installed by Republicans in the state legislatures, many of whom have waited eagerly for this moment. Some will likely pursue limits much earlier than the fifteen-week Mississippi ban that has become the default — and, according to the polls, generally popular — position. Several politically key purple states such as Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan will have to thrash it out in ways that could upend Republican chances in the midterms.

For Joe Biden, this is a moment where his doddering inability to find a path toward compromise or statesmanship is most apparent. Biden is a perfect example of the partisan devotion to abortion that is a matter of religious fervor for the current Democratic Party. When he began his career in the wake of Roe, he was an outspoken Catholic critic. He called for legislation to effectively reverse the decision and return the matter to the states. Throughout his career in the Senate, he opposed federal funding for abortion, reliably supporting the Hyde Amendment. He echoed the Bill Clinton language of “safe, legal and rare.”

But when it came time for him to ascend to the presidency, he had to kiss the Planned Parenthood ring, rejecting his entire history on the issue and dropping his support for Hyde. More recently he went further, embracing the most radical legislation ever proposed on the issue, the Women’s Health Protection Act, which would have mandated a nationwide absolute right to abortion until the moment of birth.

Biden has leaned into the Dobbs decision by calling for a national political revolution on the issue. Among other things, he has suggested a “carve-out” of the filibuster for abortion legislation. It is an act of divisive desperation — and it is unlikely to succeed. He may be aware of the uphill battle ahead: on July 8 he performed a sort of end-run, signing an executive order aimed at facilitating the use of “every federal tool available to protect access to reproductive healthcare.”

It turns out that the support for the Roe status quo, consistently inflated by poll questions that inaccurately framed the ramifications of its downfall, was always politically weaker than it seemed. Most Americans are deeply uncomfortable with the idea of eliminating a child who, thanks to the era of technologically advanced sonograms, can be seen to move and wriggle and suck her thumb. As pregnancy progresses, they’re more and more aware how short the distance is from unborn to toddling around the house at breakneck speed.

This is a political revolution. But it is also an incomplete one, and it comes at an odd time for American politics, when the baby boomers who advanced “your body, your choice” are, at long last, departing the stage, replaced by a generation of millennials who are far more opposed to abortion, and grew up with those sonogram images of little brother or sister on the refrigerator.

In the partial nature of the pro-life victory, Dobbs resembles Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which freed only those slaves in states at war with the Union. Slavery in the other states would be a problem for another day. A similar challenge presents itself for a pro-life movement that, having won the argument in the Supreme Court, must remake itself to win fifty arguments and debates across the country.

The slavery analogy is popular within pro-life circles; they are people closely attuned to the movement for abolition. As author and academic Charles Camosy put it to me in a recent interview:

There are lazy “abortion is the same as slavery” arguments out there, ones that frankly aren’t aware of history. They aren’t aware of the important differences between abortion and slavery. And that’s important to note, before I say that there’s an astonishing amount of overlap in the kinds of debates that were had over chattel slavery and the kinds of debates we are currently having about abortion… debates about, “well, you know, are they really human beings? Does the federal government really have a role in telling people what to do with how they run their businesses? Isn’t this really actually good for the slaves in some way? Aren’t those people who are against this religious nutjobs and fanatics who want to impose their religion on people? Can’t we have a more moderate position, where we say let’s repatriate slaves? Or let’s have a situation where we have different laws in different states. And we have no clear policy about the fundamental value of the equal rights of all human beings.” And again, there are important differences between the issues. But… there’s just a tremendous amount of overlap. And I don’t say that lightly.

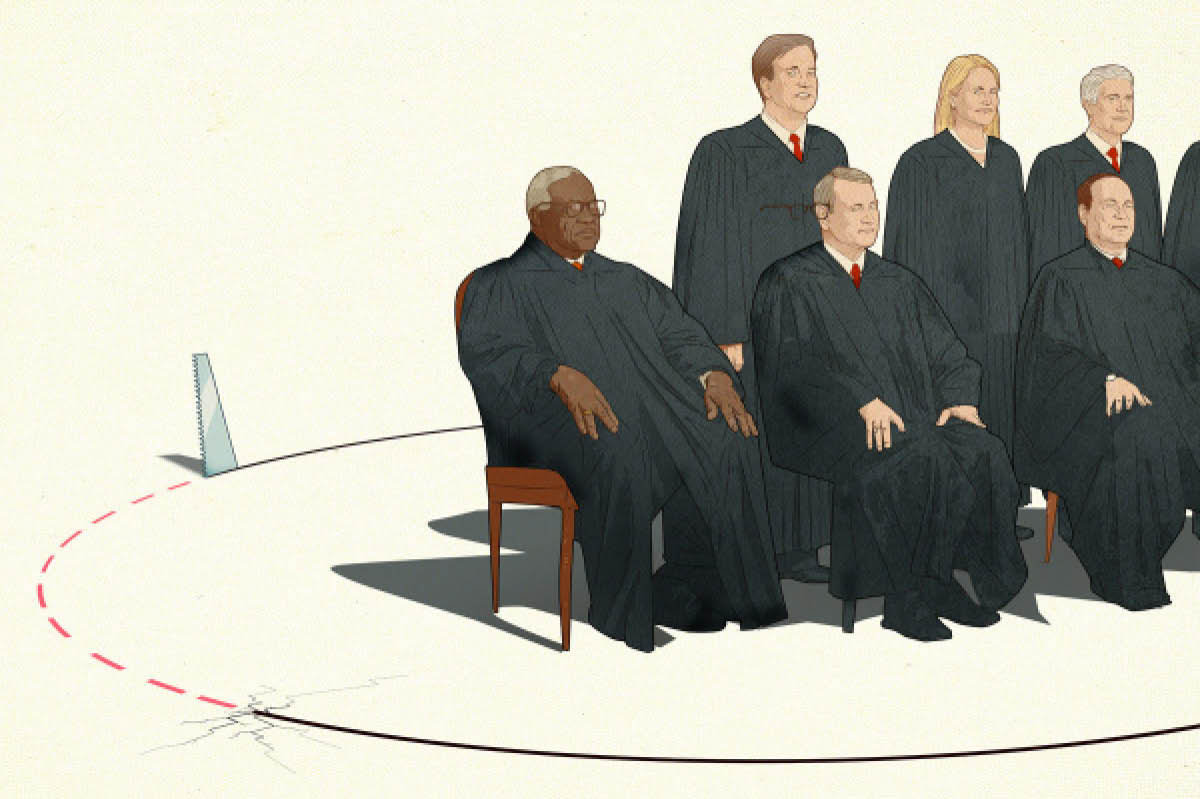

Yet just as with slavery, this was a triumph not of the inheritors of the fire-breathing John Brown, but of diligent workmanship in the spirit of Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. It was not the abolitionists who won the Dobbs victory, but the gradualists. The project began in earnest after the disappointment of Planned Parenthood v. Casey and the betrayal of Republican Supreme Court nominees Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor and David Souter. Achieving institutional change was the work of hundreds of devoted pro-lifers and their allies.

It is fitting that Dobbs’s author, Samuel Alito, was appointed to the court only after George W. Bush’s reckless decision to nominate White House counsel Harriet Miers was rejected by the conservative base en masse. Alito can be understood as the fulfillment of the gradualist conservative effort to change the judiciary — embraced not just by pro-life groups, but by the Federalist Society and the Heritage Foundation and their ideological allies in the Senate — and a rejection of stealth nominees as fundamentally untrustworthy.

It sounds like an exaggeration to say that everything will change. But everything will change. Within a decade, the abortion issue may very well be put in play as an issue for moderates within the Democratic coalition. Their extremism on the subject earned them the votes of suburban white women, but seems to have damaged them significantly with American Hispanics, a significantly larger and growing force. The opportunity for a Democrat who rejects abortion orthodoxy will be real.

And on the other side, the dedication of evangelical Christians and Catholics to the Republican Party can be questioned in the wake of a decision that largely eliminates the need for a single-issue pro-life voter to automatically pull the lever for the GOP. If you are a churchgoing Christian who cares about climate change, or rejects a hardline view of immigration policy, or believes in more social spending on healthcare for the poor, do you still owe your vote to the Republican Party with abortion no longer an issue at the national level?

This is a critical question for the coalition of the right to answer. It raises the possibility of new coalitions that appeal to the mythical center of American politics. This is why Biden, Nancy Pelosi and the rest of our octogenarian generation of Democratic leaders are so short-sighted and wrong. They thought unrestricted, taxpayer-funded abortion was an essential item of their policy agenda. It may turn out to have been holding them back all along.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.