‘Each vote counts…come and vote and choose your president. This is important for the future of your country.’ These were the words of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Friday morning as he urged people to make their voices heard in the presidential election.

Each vote doesn’t count, of course. The regime makes sure of that. Iran ‘manages’ its elections. This year, 600 people registered as candidates. That was cut to seven. The unelected Guardian Council, which consists of 12 ‘jurists’ (clerics), is responsible for ensuring all candidates are compatible with ‘Islamic values’.

What this means is that it can disqualify pretty much anyone it doesn’t like. The real reasons the council generally disqualifies people are almost invariably to do with politics rather than religion.

In 2013, everyone thought the winner would be the hardline then mayor of Tehran, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf. Instead, the (comparative) moderate Hassan Rouhani won with over 50 percent of the vote, precluding even the need for a second round. The following eight years saw repeated struggles between Rouhani’s more reform-minded circle and those around the Supreme Leader.

They won’t make the same mistake again. Among the prominent candidates the Council barred from standing were Eshaq Jahangiri, Rouhani’s first vice-president, and Ali Larijani, a conservative former speaker of parliament.

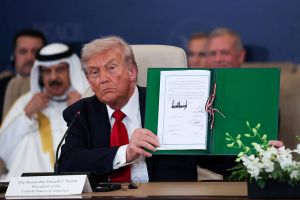

Four remained at the time of the vote: Amir-Hossein Qazizadeh Hashem, a doctor and hardliner; Abdolnaser Hemmati, governor of the Central Bank of Iran; Mohsen Rezai, secretary of the Expediency Council, which advises the Supreme Leader; and Ebrahim Raisi, chief Justice of Iran — and the overwhelming favorite.

The other three candidates conceded to Raisi on Saturday.

By clearing the way for Raisi to win, the Supreme Leader’s coterie did two things: one, they ensured their man took control of the presidency; and two: they sent a message to the Iranian people and to the world.

This is because even by the regime’s pathological standards, Raisi is a hardliner. In July 1988, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran’s first Supreme Leader issued an order (some argue it was even a fatwa — a religious ruling) ordering the execution of imprisoned opponents.

It was the beginning of what turned out to be the biggest massacre of political prisoners since World War Two. Charged with carrying out the executions was a ‘four-man commission’ later known as the ‘death committee’ — prominent among whom was Raisi.

The executions went on for five months — thousands were killed (some estimates are as high as 30,000). Most of the victims were members of the Iranian opposition group the People’s Mujahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI), or the Mujahedin-e-Khalq. To this day the regime denies the massacres took place.

Ahmad Ebrahimi was in Tehran’s Evin prison at the time. A supporter of the PMOI, he served 10 years from 1981-1991, before finding political asylum in the UK.

‘Raisi is a murderer,’ he tells me. ‘He was a mass murderer in 1988. The regime tries to say these mass executions never took place but me and people like me are doing our best to get the truth out.’

He has strong feelings about the regime — and the election.

‘It’s a sham,’ he says. ‘The regime uses these elections to legitimize the government, to say it has the support of the people. But it’s nothing to do with that. The people have proved that they do not accept the regime — indeed they are opposing it through demonstrations and protests.’

At 9 a.m. on August 1988, along with 60 others, Ebrahimi was taken, blindfolded, to a corridor in the building where the committee was in session and left there until 6 p.m. in the afternoon. Once inside the ‘court’ his blindfold was taken off, and there he saw Raisi among the four-man commission. He remembers Raisi talking about handing down death like it was nothing.

‘Back then, he wore normal civilian clothes — not the clerical garb he wears today,’ he said.

‘It wasn’t generally known that they were executing prisoners en masse,’ he continues. ‘But words had come back to a few of us that they were killing PMOI members so when it was my turn to speak, I said I had never been a full member of the group. So I survived.’

I spoke to Ebrahimi on Thursday just after he had attended a demonstration outside the Iranian embassy in London. Now he is among many campaigning for the British government to take a tougher line on Iran.

‘We hope that the British government takes note all the executions and human rights going on in Iran. We want the UK government to make any dealings with the regime conditional on it halting the executions and starting to pay due attention to human rights in Iran,’ he said. ‘This regime has gone on for 40 years, killing and torturing. The world has to do something – Iranians are being oppressed.’

With the results from Iran’s sham election, it seems almost certain that their oppression will only get worse.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.