It’s understandable that, in a crisis, politicians reach for wartime metaphors — but they don’t always fit. There was the ‘war on terror’. Now we have politicians talking about the need to vanquish COVID-19. This is about more than language. There’s a big difference between a COVID-19 eradication strategy and one that seeks to find a way to live with this virus, in the way we learned to live with Swine Flu (or, as it’s now called, flu.)

In the second term agenda announced by his campaign ahead of the Republican National Convetion last month, Donald Trump pledged to ‘eradicate COVID-19’.

The British prime minister is also leading by example. Addressing a committee of Conservative MPs on Thursday, Boris Johnson said: ‘We have to make sure that we defeat the disease by the means we have set out.’ Later he said: ‘We must, must defeat this disease.’

Last week, Johnson’s rival Sir Keir Starmer told the PM that, among other things, he should ‘get on with defeating this virus.’

Are they all aiming for elimination? If so, it’s a new strategy – and a worrying sign of mission creep. Back in March, we were all requested to ‘buy time’ to stop hospitals being overwhelmed by a sudden surge in cases. The idea back then, in so far as it could be divined, seemed to be that we would temporarily protect healthcare workers, then get used to living with the virus once the acute danger had passed. But over the last few months, while the science has become clearer, the politics has changed. Preventing a surge of deaths seems to have morphed into minimizing the number of cases in all age groups, which is a completely different proposition.

Of course, it can be good to have ambition and aim high. President Kennedy’s rallying call to land men on the moon and bring them safely back galvanized great things. But as the saying goes, ‘You should be careful of your ambitions, because you might achieve them.’ Having unattainable ambitions can be expensive, harmful, and, when pursued on a political scale, cause untold misery, as we all know from the disheartening historical litany of failed utopias.

In this case, it’s clearly going to be easier to control people than to control coronavirus, and, with depressing predictability, that’s what governments around the world (with honorable exceptions such as Sweden) are setting about doing. So it makes good sense to examine what, exactly, we can mean by ‘defeating’ a virus.

There is only one example of a human viral disease where ‘defeat’ has been comprehensively achieved, and that is smallpox. In its day, which was not that long ago, smallpox was a horrible disease. In 1950, it was still killing over a million people every year in India alone. In 1967, it still menaced three-fifths of the world’s population, killed one in five of those infected, and left many more scarred for life or blinded. It was a prime candidate for medical intervention.

How did we succeed with smallpox, and could there be lessons for coronavirus? Although smallpox virus can enter through skin abrasions when people are in close contact, the most important means of transmission was the respiratory route: inhaling the virus in crowded conditions. Smallpox infected cells in the lung and then spread around the body, infecting many organs. These included the skin, where it produced the pox pustules in a characteristic centrifugal distribution, i.e. mainly affecting the face and extremities, allowing it to be clinically distinguished from chickenpox, which mainly affects the trunk and face.

The ability to clinically distinguish smallpox from other diseases was vital in helping to eradicate it from the world, allowing index cases to be isolated. And, crucially, it was not infectious until the patient started to develop symptoms — by which point they were usually sufficiently ill to be in bed, thus minimizing transmission. There were hardly any asymptomatic infections. Very helpfully, smallpox had a typical incubation period of about 12 days — meaning that once an index case was identified, almost two weeks were available for tracing contacts and isolating them until they could be shown to be non-infectious.

There’s more. Vaccination against smallpox was known to be safe and very effective, and had been applied with increasing reach since the end of the eighteenth century. Smallpox was a stable DNA virus with only two types (major and minor), which looked exactly the same and responded identically to vaccination. And there was no animal reservoir for smallpox: it infected only humans.

These key features, combined with the awfulness of the disease, led to the motivation to eradicate it from the globe, and also aided our ability to do so, since eradication means that recognition, isolation and elimination of the disease much reach the furthest, poorest, least technologically advanced corners of the planet to be successful. Smallpox became extinct in the wild in 1979, and marked a genuine victory for humanity and ‘defeat’ for the virus.

However, the lessons for COVID that governments should be learning are almost entirely reciprocal. SARS-Cov-2 is a highly mutable RNA virus that spreads on the wind, like all successful respiratory infections, much more effectively than smallpox. There are animal reservoirs, a very high proportion of asymptomatic cases, and huge differences in disease severity in different segments of the population.

There are no clinically-defining features sufficiently specific to be useful in case isolation, and a relatively short incubation period of about five days on average, making case isolation virtually impossible and massively disruptive if it were pursued with vigor. The reliance on testing to identify cases, requiring massive resources, and generating severe problems of its own on any reasonable assumptions about accuracy and sensitivity, means that it’s difficult to know what the burden of serious and mild disease is, even in developed countries throwing everything they have at it.

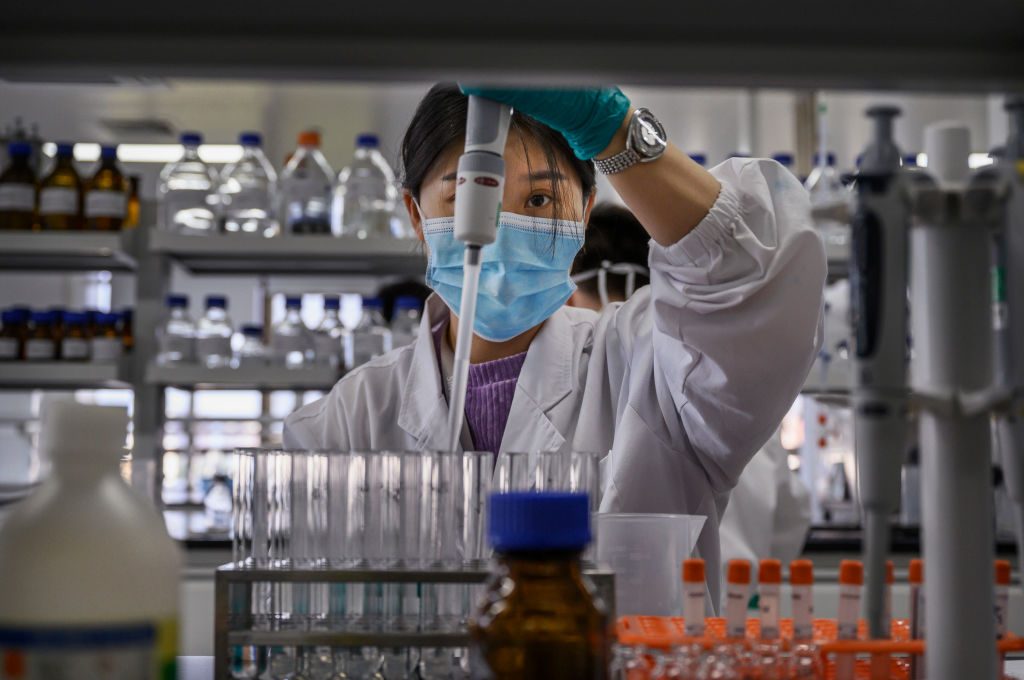

Also, there’s no vaccine. Despite much current optimism, coronaviruses have staunchly resisted attempts at vaccine development before. Even if a reasonably effective vaccine is found, its benefits may well be short-lived — the mutability of the virus means COVID may mutate away from control.

So where does this comparison leave us with COVID? Recognition is difficult, isolation very difficult and comes at enormous societal cost. Which is why elimination is, almost certainly, impossible.

This means we must learn to live with COVID. ‘Defeat’ of the virus is a false and dangerous ambition. The very large proportion of the population for whom COVID represents a small new risk should allowed to get on with their lives normally. The proportion for whom COVID represents a larger risk should be presented with the information, encouraged to make their own risk assessments, and helped to take avoidance action (if that is what they wish to do: some may prefer to keep seeing and hugging their family and regard COVID as one of the many viruses that human-to-human contact can bring).

***

Get a digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $3.99 a month

***

What’s more, once a nation decides to live with a virus, relatively asymptomatic spread of the virus among large sections of the population is a good thing because it speeds our progress towards collective immunity — which is where, irrespective of what governments do, we will end up in equilibrium with the virus. Through vaccination or infection, this is how viruses dwindle. The main differences between countries will be in the size of the own goals that their responses cause in the meantime.

Ironically, there’s a lesson here from the only other human viral disease that we have nearly ‘defeated’: polio. Polio has been knocked down by over 99 percent by a vaccine using a live, but weakened form of the virus. This is taken by mouth, replicates in the gut, and is excreted in the feces. In most parts of the world this means that the virus then spreads effectively in the community: so asymptomatic spread to those not formally given a dose of the vaccine has actually been essential to the success of the program.

The fatality rates from COVID do not bear comparison with great scourges of the past like smallpox and plague, so coercion in the name of ‘defeat’ for the virus is not justifiable, as well as not being realistic. An unrealistic ambition of ‘defeat’ for the virus might sound good in speeches, but it would be unachievable as a policy — and the pursuit of this policy, with the suppression measures it would bring, would cause harm. Our leaders should choose their words carefully, and their COVID policies more carefully still.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.